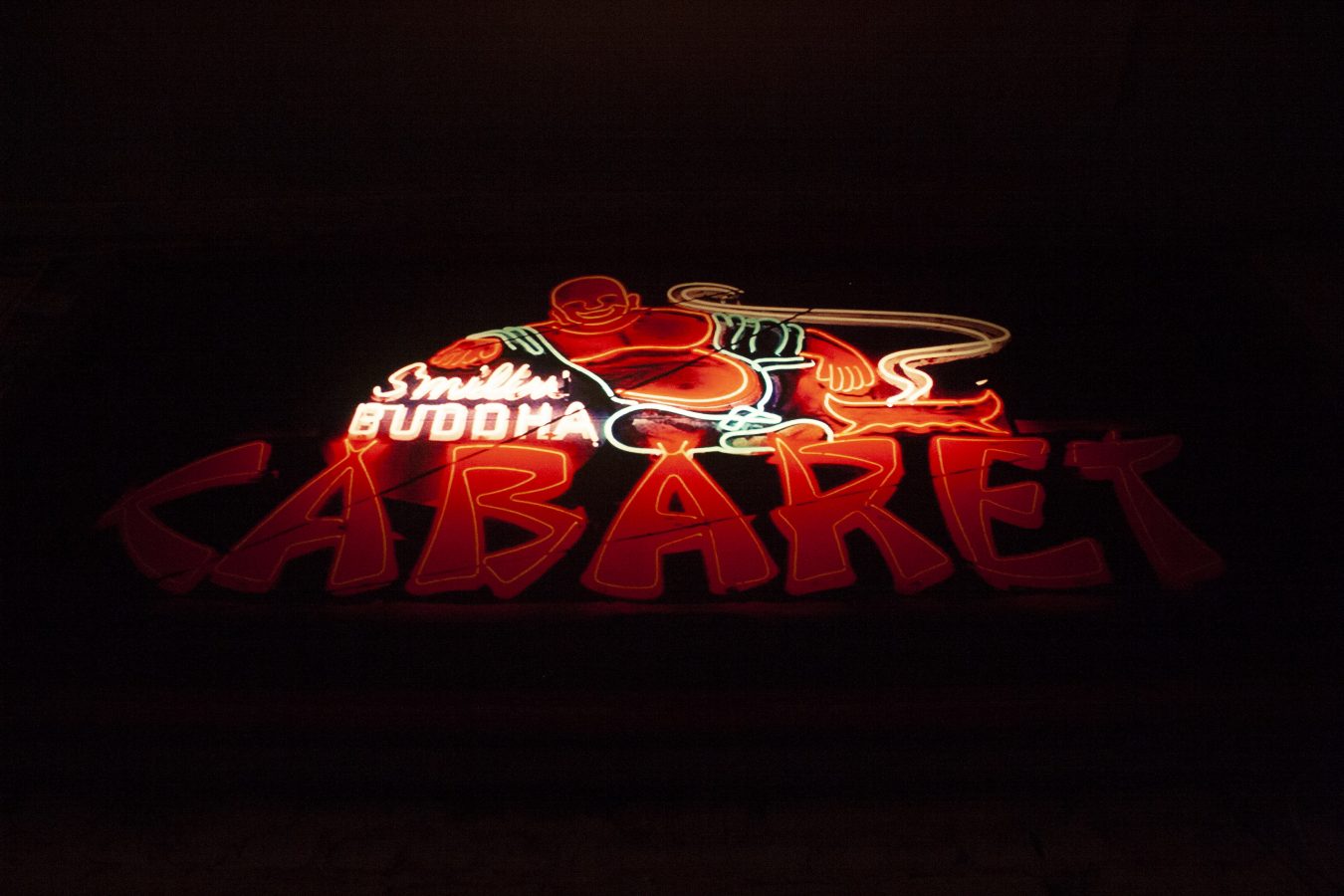

For more than 60 years, the Smilin Buddha Cabaret has been one of Vancouver’s most unique underground hot spots.

First, it was an “exotic” supper club that bridged the divide between the east and west sides; later, it became the premiere venue for city’s burgeoning punk scene, featuring acts like Vancouver’s own D.O.A. and San Francisco’s Dead Kennedys. Its distinctive neon sign was once taken on tour by Canadian rockers 54-40 (who also named an album after it). Legend has it, the space once hosted Tina Turner and a young Jimi Hendrix. And since its reopening in 2013, the legendary venue—recently rebranded as SBC Restaurant—has returned to its underground roots, serving a dual purpose in the Downtown Eastside as the only combination music venue-meets-indoor skateboard ramp.

“There’s been a need for an indoor athletic facility in the inner city, and we thought it was important to have that,” explains co-owner Andrew Turner. “We’re running a business based on food and drinks and concerts, but we’re using that to subsidize a public service. Our initiative was to set up a social enterprise on the 100 block of East Hastings, where we could address a need in the community, and also provide a safe place, help out, give back, and provide a couple of jobs.”

In Turner’s estimation, the ramp provides an accessible indoor space for thousands of skateboarders each year, largely during the wet winter months. And while the owners have decided to move in a new direction, SBC Restaurant still retains a solid connection to its past. Sound is done by longtime D.O.A. producer Cecil English, and one wall remains papered with photos of the venue’s punk-rock heyday. Even the 60-foot skate ramp, the largest of its kind in British Columbia, has a history of its own: built out of a number of other ramps, it includes pieces that once belonged to Canadian skate legend Kevin Harris, some from the Crack Pipe (a former ramp on Powell Street built by Antisocial Skateboard Shop), and even portions used during Expo 86.

“I remember seeing guys skate at Expo when I was a kid,” Turner recalls. “I used to go down to China Creek and watch the older guys skate and do it. It’s an individual thing. It’s affordable, it’s accessible. It doesn’t have rules or structure, but it does take commitment. I think it’s a pretty unique activity in that sense. It’s just always been a way to get out of the house and be on your own and get away from everything.”

Turner and co-owner Malcolm Hassin have a long history with both skateboarding and the neighbourhood—Turner as a contractor, and Hassin in the mental health field. Hassin has been involved in a number of do-it-yourself skateparks over the years, mostly in Victoria; in fact, an indoor skate ramp like SBC Restaurant’s is an idea Turner has had for more than a decade. “It goes way back,” he says, chuckling. “I did the entrepreneurship program at Langara and designed an indoor skate ramp. But then, I realized at 22 years old that I wasn’t remotely ready to do it.”

As for the Smilin Buddha’s history, it can sometimes be difficult to separate truth from doctrine. Many of the stories from its early years have been retold through word of mouth and aren’t supported by newspapers or historical evidence. Opened as the Smilin Buddha Dine and Dance in October 1952, the space at 109 East Hastings was the brainchild of Albert Kawn and Harvey Lowe, both sons of Chinese immigrants who were well-known in Vancouver’s business community (Lowe was also a former yo-yo champion who once taught Julie Christie how to smoke opium for the film McCabe and Mrs Miller). Advertised in the pages of the Sun as “Vancouver’s newest and smartest nightclub,” legendary columnist Jack Wasserman declared it to be “the last word in supper clubs embodying all the charm of the Orient.” And while the goal was to provide an exotic environment for the city’s white working class (a trend at the time, best exemplified by tiki establishments like The Waldorf), the Smilin’ Buddha during its first decade was merely one of a dozen cabarets operating in the East End. In the ‘50s, the focus was more on food and socializing than it was on music; usually, the only act on the bill was the Smilin Buddha Orchestra—although in those years, the venue also featured novelty acts, and sometimes a weekly talent show.

In 1962, Lowe and Kawn sold the venue to Lachman and Nancy Jir. The Jirs owned the Smilin Buddha well into the 1980s, bringing in local rock bands, psychedelic acts, female impersonators, and—once fully nude dancing was legalized in B.C. in 1972—strippers. Public opinion of the Buddha during this period wasn’t particularly charitable. In 1979, local music journalist Tom Harrison labelled it “a hole.” Ubyssey columnist Lorenne Gordon joked about its terrible entertainment. In 1977, a Vancouver Police report called the Smilin Buddha “the worst of all cabarets in the Downtown Eastside for drunkenness and other infractions” and demanded Lachman Jir appear before council (it’s also during this period that a young Jimi Hendrix was supposedly fired by Lachman for playing too loud).

However, come 1979, the club’s seedy reputation had begun to work in its favour. Owing to its run-down aesthetic and spot in one of the country’s poorest neighbourhoods, the Buddha became a symbol of the growing punk scene—a place where emerging bands such as D.O.A. could hone their skills in front of an audience. While the Jirs weren’t initially thrilled (they stopped their debut punk act, K-Tels, early and removed them from the premises), the venue’s exploding popularity quickly changed their minds. A police raid in 1979 also helped the Buddha’s reputation; henceforth the club was regularly filled beyond capacity, and performing there became something of a rite of passage for Vancouver’s punk rockers.

By the early 1980s, though, punk had outgrown the Buddha. It became one of many venues that catered to the local scene, and most of the acts who made it famous had moved on. The club was virtually destroyed by a fire in November of 1983, and from then on, it languished. Lachman died in 1988, and for several years, his son Robert took over the management; at an unspecified time in the 1990s, it was sold, reopening for a brief, horrible moment as the Smilin Sports Cafe (notable only for its inclusion in a 1996 Vancouver Police Department report as being “the worst overall problem premises in the 100 East Hastings block”), before city council ordered it closed in 1997.

The space sat empty and decaying until 2010. In the interim, it was purchased by the notorious Sahota family, known widely as Vancouver’s worst slumlords. And, while Turner acknowledges that the condition of the building was one of the factors that allowed him and Hassin to afford it, he recalls that when they took over the space, they had a lot of work to do. “It was really run-down,” he says. “I’m not sure that the building would have lasted for another year or two. And it’s still a work in progress. We’ve done it on a shoestring, which you can see when you walk in. There’s nothing flashy here—which is kind of neat, because everything that happens here happens because of the community and the people who make it what it is.”

Coordinating with the City of Vancouver and working with city planners (including Michael Gordon, himself a skateboarder), the team managed to perform the necessary renovations, including a large electrical upgrade, to get the Buddha up to code. Today, SBC Restaurant is more than just an alternative-culture favourite. Back in 2013, it was named a “Place That Matters” by the Heritage Vancouver Foundation; its iconic sign, meanwhile, has been restored and now resides in the Museum of Vancouver. And as for the future, there are plenty of changes ahead. For one thing, Turner himself is taking a step back, leaving the business in Hassin’s capable hands. Beyond that, both Turner and Hassin are cryptic (“There’ll be some changes coming,” Hassin says), but they are quick to point out that the core of SBC will remain the same: providing a community space for Vancouverites—underground and otherwise—to play, to skate, and to connect.

“It’s not just about skateboarders,” Turner notes. “It’s about linking up people from different social and economic backgrounds. We’ve got elders that hang out here, we do fundraisers for community events. It’s a skateboard ramp, but it also becomes a community hub. And it’s been super positive and rewarding to see that happen—watching people make use of and enjoy the space we’ve created.”

Read more from the Community.