In Japan, don’t ask for sake. What Westerners call sake is actually nihonshu—“sake” refers to all kinds of alcoholic beverages. The Japanese rice wine has been made in the country for thousands of years, with “modern” sake emerging with the advent of wet rice cultivation circa 300 BC. Today in North America, sake is beginning to gain ground as a beverage to be paired with not only Japanese cuisine, but Western as well.

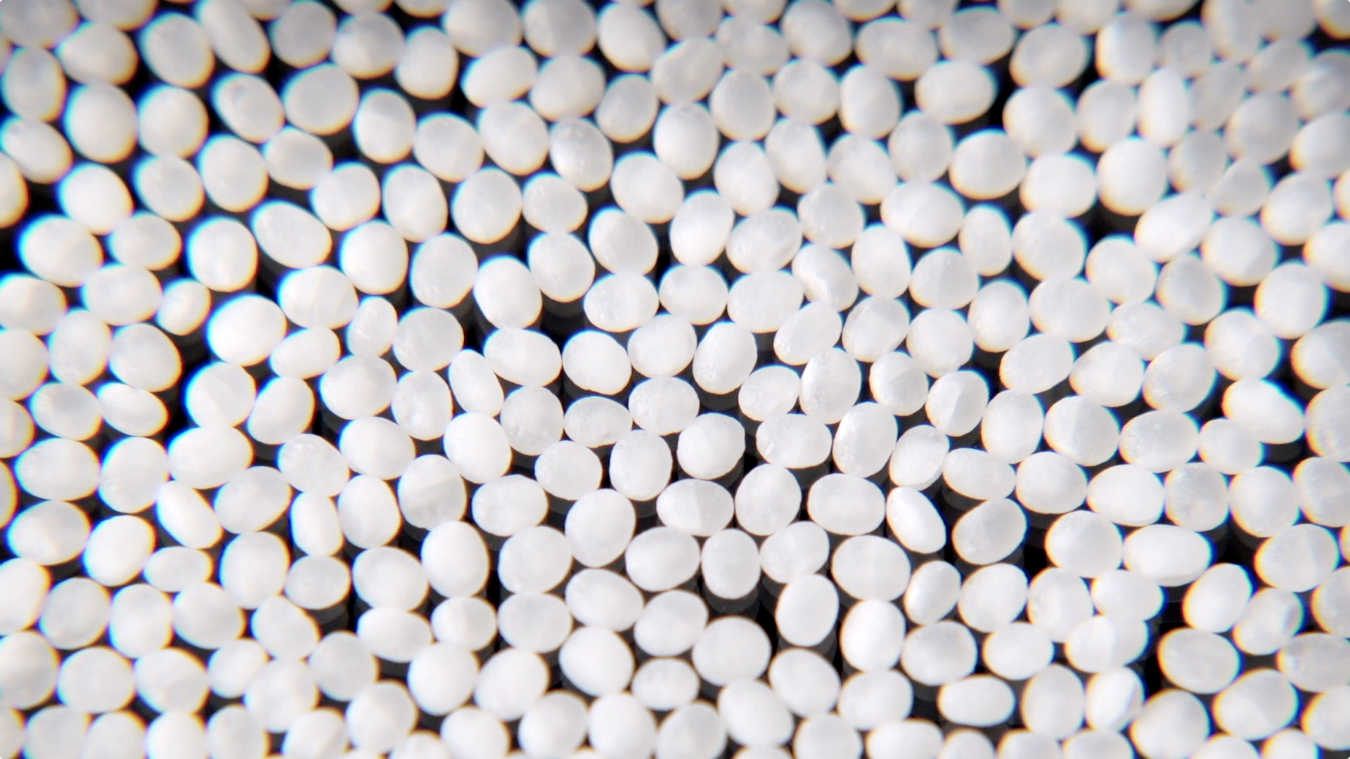

Rice

Like most alcohol, it all begins with the grain. In sake that means rice—non-sticky japonica rice. This rice, also known as sakamai, is a short, smooth grain high in starch (rice with a distinct and noticeable opaque centre is ideal to make sake with). In this case the grain is polished, which mills it into smooth pearls. There are varying degrees, called seimai-buai, to which this process can go to—as an example, seimai-buai 40 per cent indicates that of 100 kilograms of brown rice, 40 kilograms were polished.

Water

Within this process, there are thousands of variants that make sake unique. Water, an essential part of production, perhaps yields some of the greatest regional differences. In the north of Japan, the water is generally softer, producing lighter, drier sake. Alternatively, in the southern regions there are active volcanoes, making the ground younger, thus allowing the water to absorb more minerals. This yields stronger, more savoury sake. Use region as a general guide when buying and pairing sakes.

Fermentation

Once the rice is polished, it is washed, soaked, and steamed in preparation for the fermentation process. In ancient times, the starter would be sourced from rice chewed into a paste, allowing saliva to active the culture. Today more hygienic methods are employed, with yellow Aspergillus oryzae mold used to make the starter, or koji-kin. This mold is mixed with rice and water and then left to ferment. Pressing the mixture to extract the liquid is then done, either with the traditional canvas and box method, or by more modern, mechanical means. The liquid from here is filtered, distilled, pasteurized, and left to age. Aging dates range from three to six months—like with grape wine, the longer the sake sits, the smoother and more developed it is.

Varieties

A Junmai Daiginjo grade refers to sake with at least 50 per cent milled rice and a soft, fruity aroma and taste. At a recent Japan Rice and Rice Industry Export Promotion Association event at Blue Water Cafe, a Junmai Daiginjo from Gekkeikan in Fushimi, Kyoto was served: delicate and sweet with pear notes wafting up and coating the palate. The sake was paired with a dish of rice with foie gras and black truffle from New York chef Tadashi Ono, author of the cookbooks Japanese Hot Pots and Japanese Soul Cooking. In contrast, a Junmai Nama (“nama” meaning unpasteurized) from Hakutsuru in Nada, Kobe had a strong, mineral bite that played well with meaty Wagyu flat iron steak and butter-poached Alaskan king crab from Blue Water chef Frank Pabst.

Whatever the variety, serve sake cold in a wine glass to allow the aromatic notes to waft up. Savour the smells, and let the many layers of taste coat your tongue. Spit, however, you should not. Kanpai to that.