A successful athlete … must block out the rest of the world, must concentrate on the task at hand. There will always be crises, there will always be emergencies; the athlete who is going to succeed under pressure must learn to draw into the body, to perform despite any distraction.” —Angie Abdou, The Bone Cage

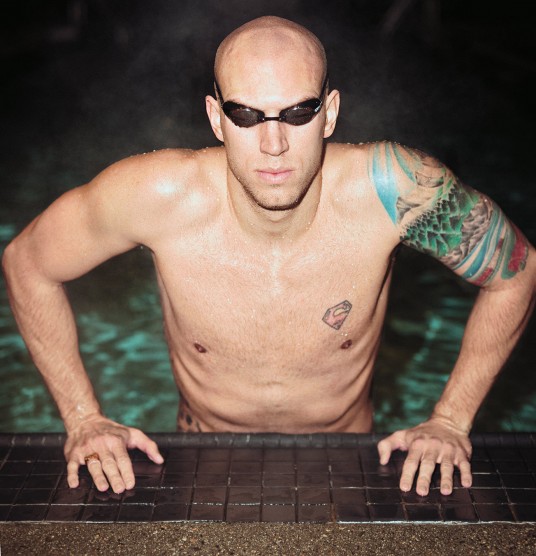

A tall, solitary figure strides across the pool deck at the UBC Aquatic Centre. He ambles toward his coach to chat about the day’s practice before flopping onto a mat for an easy stretch. Muscles loose, he grabs a kickboard and pull buoy out of his gear bag, dropping them at the edge of the pool. The swimmer snaps his goggles on and shakes the tension out of his arms. A quick pause for a breath before he dives into the pool, breaking the surface with an emphatic splash. His sinewy, muscular physique slices through the water with precision and ease. Length after length, his arms pull him through the pool—a study in strength and grace.

This is how Canadian national swimmer Brent Hayden begins each training session. He toils away in relative obscurity, the rhythm of his strokes broken only by brief pauses to adjust his goggles or get a new set of instructions from his coach. Nine practices each week. Over 20 hours in total, averaging 5,000 metres per session. Innumerable kilometres over the course of his storied career, culminating in a number one world ranking for the 100-metre freestyle at the close of the 2010 season.

It’s a league beyond Hayden’s start in racing at age five, having failed swimming lessons twice before that. “I was scared of the water and did nothing but distract the other kids,” he reminisces. By Grade 7, though, Hayden started moving up through the ranks, regularly placing in the top three at meets. At about the same time, he began taking Isshin-Ryu karate. “I was the kid who wanted to play all the time, and karate taught me discipline and a better awareness of body mechanics.”

Sensei Tom McDonagh had a huge influence on the young swimmer; when McDonagh died a year ago, Hayden paid homage to him by adorning the right side of his already-illustrated torso with a Japanese-inspired cloud and three stars tattoo. “The three stars are on our karate crest and they signify a couple of things: the three styles of karate that make up Isshin-Ryu, and the battle of mind, body and soul. I’ve been dealing with a lower-back problem for the last three years, and it basically symbolizes my battle to stay positively motivated.”

An auditory quirk affecting his performance off the starting blocks is another challenge that Hayden continually trains to overcome. “I had a hearing test done when I was little, and at first they said I was completely deaf in one ear. Turns out my hearing isn’t wired properly—too many neurons are firing, and it causes a lot of brain fatigue. Sounds take a split second longer to register with me, and that hampers my reaction time.” Ongoing work with a specialist over the past couple of years has all but eliminated the deficit. “Our primary focus is to get the right body mechanics to get off the blocks quickly and efficiently,” he says. Once known as a come-from-behind swimmer, his starts are now among the best in the world.

Hayden’s rise through the international ranks led to his first Olympic games in 2004. But the heady excitement of being in Athens was marred by a horrific event that would threaten to derail the progress of his career. On the eve of the closing ceremonies, then-19-year-old Hayden and a few fellow athletes emerged from celebrations at a nightclub to find themselves amid a raucous crowd heading toward a public demonstration. The group ducked back into the nightclub doorway to escape the fracas, but Hayden was singled out and dragged back into the street by a police officer. As his horrified teammates watched helplessly, he was violently kicked and struck with batons by a group of policemen who ignored his attempts to identify himself as a Canadian Olympic athlete. Hayden lodged an appeal with the Greek government to no avail.

The incident left him bruised and battered. “I didn’t regain full movement in my arm for two weeks,” he recalls matter-of-factly. Beyond his physical injuries, though, the mental and emotional trauma Hayden suffered was immeasurable. He was forced to miss the 2005 Short-Course World Championships, and the emotional fallout nearly stopped him in his tracks as the trauma of that night in Athens closed in around him. “There were training days when I’d have a mental breakdown in the pool—I didn’t know if I could continue swimming anymore.” Counseling helped Hayden exorcise the emotional demons that haunted him. “I wasn’t going to let this define me as a swimmer. I was determined to fight and make it back to the World Championships, to really make a stand. That’s when my career really started.”

Of Hayden’s numerous titles, he cites his 2007 World Championship gold medal for 100-metre long-course freestyle as the most meaningful. The spectacular race ended in a heart-stopping dead heat between Hayden and Italy’s Filippo Magnini for first place. His win not only captured Canada’s first swimming World Championship since the late Victor Davis’s triumph in 1986, but it also fulfilled “the most difficult promise [Hayden] ever had to make.” Before leaving to compete in Australia, Hayden visited his grandfather, who lay dying in the hospital. He remembers catching his grandfather in a lucid moment: “I promised him that I was going to win him a medal. I didn’t say what colour, just that I would bring a medal back for him.” Sadly, his grandfather died four days before Hayden’s victorious swim, but his pledge kept him focused. “ ‘I’ve gotta do something amazing here,’ I kept saying to myself. I wasn’t the fastest swimmer in Melbourne, but that’s what motivated me.”

“I was determined to fight and make it back to the world championships, to really make a stand. That’s when my career really started.”

Hayden recently clocked a pair of stellar swims at the Delhi 2010 Commonwealth Games, claiming gold medals in both the 50-metre and 100-metre freestyle. But Hayden’s return to Vancouver was utterly without fanfare. Despite the myriad of accolades that he’s earned, Hayden’s athletic success hasn’t translated to the celebrity status enjoyed by his swimming counterparts. American Michael Phelps is a household name south of the border; Eamon Sullivan and Ian Thorpe of Australia live in “the only country in the world that can make a millionaire and idol of a swimmer even before he dips his toe into an Olympic pool,” according to Gary Smith in the November 1999 issue of Sports Illustrated.

People often point at the Canadian government for slacking in its support of amateur athletics, but Hayden takes a different tack. “The government does do enough. It provides us [carded athletes] with enough money to cover basic living expenses every month.” He’s not off the mark. Sport Canada’s Athletic Assistance Program grants carded elite athletes up to $18,000 a year, facilitating their pursuit of national-level training. “It’s the corporate world that needs to step up to the plate,” Hayden states emphatically. He is one of the lucky few who has secured corporate sponsorship to make up the budgetary shortfall, thus enabling him to meet the demands of full-time training. Sadly, most Canadian amateur athletes are not as fortunate. “The private sector should run sponsorship programs to nurture developing athletes. Take Australia, for instance. Kids in Australia don’t have to pay for their travel expenses to attend swim meets because there’s a program in place to give them the competitive experience they need. One of them is bound to be the next Ian Thorpe.”

Hayden points out that Canada loses many promising young competitors to the financial burden of elite-level training, yet the value of an athlete’s contributions to a nation unquestionably supercedes monetary worth. “During the 2010 Winter Olympics, people were more proud to be Canadian than at any other time in history,” he says. “All those gold medals helped unite the country for those two weeks more than any politician ever has.” Hayden has tirelessly gifted Canada with 22 years in the pool. “Pure and simple, I love the sport. I’m happy to be Canadian and doing what I can for my country.”

His current goal: to win gold at the 2011 World Championships in Shanghai this summer and the 2012 Olympics in London. Hayden speculates on what lies down the road for him beyond London. “We’ll see. I want four Olympics—I know my mind is in it, but it really depends on my back and if I can physically swim.” In the final reckoning, however, the mark of the man transcends his accomplishments in the water. “Swimming is definitely a huge part of me and who I am, but I don’t really let it define me. It’s what I do now, but not really who I am. Someone asked me just before the Commonwealth Games, ‘What would winning a gold medal mean to you?’ My answer: ‘If I can’t be good enough without a gold medal, I won’t be good enough with it.’ ”

Freestyle Swimmer Brent Hayden was photographed at the Westin Grand pool in Vancouver.