Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon refers to him in Lee Hazelwood tones. Jarvis Cocker has championed his burnt-out ballads on the iconic Sunday Service BBC Radio program. And last year, after he recorded a gritty Crazy Horse-inspired LP, Good Hand, Bad Hand, the esoteric Vinyl Factory label released a deluxe edition of it using Abbey Road’s historic record-pressing machines—the ultra-limited copies instantly disappeared, fetching high sums with collectors. It would seem that after four decades of critical acclaim in the art world, Rodney Graham is finally starting to be noticed for his music.

Since the early 1980s, the Vancouver-based artist has explored cultural and intellectual histories across multiple disciplines including photography, film, painting, and performance. It is his work as a visual artist that has garnered him the most recognition; lesser known, however, is his vast catalogue of recordings and musical pieces. Music has always been central to Graham’s life, and references to his love of abstruse and eclectic music histories permeate much of his art practise and work. His guitar skills were first documented in the early ‘80s, when he formed the Devo-obsessed art school band, UJ3RK5, alongside Jeff Wall and Ian Wallace (who would later become renowned artists in their own right). Their four-song debut EP on the Quintessence record label is long out of print; however, Emily Carr Press recently produced a two-LP bootleg of their 1980 performance opening for Gang of Four at the Commodore Ballroom.

After UJ3RK5, Graham focused on his visual art, but gradually returned to producing music and LPs to accompany and inform his work. He released a steady stream of recordings as the Rodney Graham Band, including The Bed Bug, Love Buzz, and Other Short Songs in the Popular Idiom (1999) and I Am a Noise Man (1999), which were envisioned as soundtracks for listening lounge installations in gallery spaces. Graham’s Getting It Together in the Country (2000), What is Happy Baby (2000), and Rock is Hard (2003) featured members of Vancouver bands The Evaporators, The Smugglers, and Copyright, and these recordings are the sonic foundations of some of his film works.

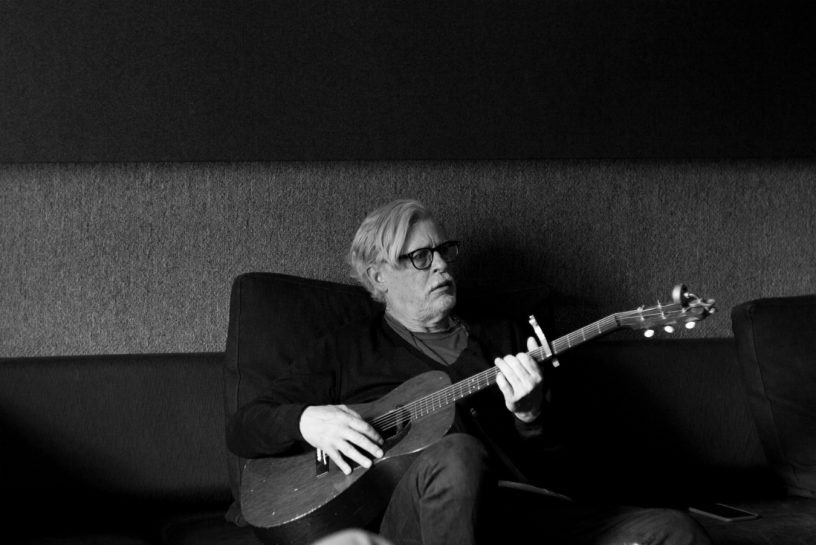

Anyone looking for insight as to how music interweaves into Graham’s work just needs to go guitar shopping with him. Heading to Exile on Main Street—his favourite local spot for boutique fuzz pedals, tape delays, and additions to his already bounteous collection of vintage amps and guitars—Graham is all about the music. It is no secret that he is obsessed with tone. (Before recording in the studio, Graham gets lost in the details—researching, for example, the exact signal path that leads to Brian Jones’s signature teardrop sound.) Graham picks up a small double-O acoustic guitar and plucks out a few random notes. It is similar to the tiny orchestral bodied pre-war Martin he fingerpicked during How I Became a Ramblin’ Man (1999). In this nine-minute film loop, Graham plays the role of a lonesome cowhand who rides horseback through creeks and canyons looking for an idyllic spot to sing his forlorn song. It is what Graham calls a “proto-music video”, exploring western film tropes while allowing him to channel his love for early Gene Autry ballads.

This is a motif that Graham explores again in video form for Phonokinetoscope (2001). Here, he evokes a character inspired by Albert Hoffman, who reportedly invented LSD, and drops a tab of Mad Hatter LSD while riding his bicycle through Berlin’s beautifully lush Tiergarten. To soundtrack the piece, the Rodney Graham Band riffed on a 14-minute psychedelic jam inspired by Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett and the massive volumes of Black Sabbath. Graham then pressed the music on record and constructed an installation that linked dropping a needle on a turntable and its rotation with the projection of the 16-millimetre film. Graham’s love for early Pink Floyd also is apparent in a later super 16-millimetre film piece entitled Lobbing Potatoes at a Gong 1969 (2011). Integrating a story about drummer Nick Mason throwing potatoes at his gong during an extended freak-out jam, Graham re-enacted the scene as a fictitious Fluxus performance piece.

At the guitar store, the talk turns to a cheap copy of the classic hollow body Hofner bass that Paul McCartney picked up during The Beatles’s Hamburg years. Graham has the real thing, and down at the Warehouse Studio, where he is finishing up tracking his latest LP, entitled Gondolier, he encourages his long-time bass player, John Collins, to use it to overdub an improvised feedback solo over the outro of the leadoff track “Getting Out of Downtown”. Gondolier captures Graham and his crack band in their most immediate and relaxed state. The songs have a lush, late-night vibe that moves in similar circles as the old greats such as Scott Walker, Mickey Newbury, and Tim Hardin. The sublime flourishes of pedal steel and smokiness of sax lines work nicely with Graham’s lyricism, perhaps nowhere more obviously than on the album’s dreamy acoustic ballad “Luigi Tenco”.

Here is a guy who had it all, then he blew his mind in a music festival

He should have let it go Luigi Tenco, turn the lights down low in old Sanremo

Graham admits that the song is one that he has reworked over and over for the last 10 years. To overcome this writer’s block, Graham even plotted a visit to Sanremo’s Italian Song Festival and the site of Luigi Tenco’s tragic fate as an obscure ‘60s Italian pop singer who was pushed against his will to perform in the spotlight.

Then there is Graham’s own emotional centrepiece, “Pretty Rattled”, which has a slow-building, laidback feel. Graham leads off sounding like Bill Callahan deadpanning along to a simple progression of guitar chords; then slowly, the bass and drums creep in and accompany him as he croons on about being back in the saddle again and rambling over a landscape that is getting on his nerves.

Forty odd years on the gin and juice, I hitched my wagon to the wrong caboose

This line recalls Kim Gordon once musing if Graham is “a musician trapped in an artist’s mind or an artist trapped in a musician’s body?” But the truth is, only he knows.

Read more music stories here.