This excerpt is published with permission from Land of Destiny: A History of Vancouver Real Estate by Jesse Donaldson, published by Anvil Press, © December 2019.

In 1901, Vancouver was a town of 26,000 people and 46 real estate firms, writes historian Jesse Donaldson. This is the story of our city’s first major real estate boom around the turn of the last century—and how it crumbled.

“WE WANT HOMEBUILDERS,” declared an ad in The Vancouver Daily Province in June of 1906. “Not Speculators, as only about thirty lots are in this division, so come early and secure yours and give your youngsters the chance to have their cheeks browned by the Southern airs blowing over the rippling waters of the Gulf and the Pacific Ocean, their lungs strengthened, and their eyes brightened.”

… As Vancouver expanded, landowners continued to open up new areas for development, including the nearby municipality of Point Grey, and much of that property was quickly snapped up by wealthy industry insiders. In the autumn of 1906, some $86,650 worth of Point Grey property was purchased at auction in a single afternoon, by realtors who handily outbid individual buyers (property speculator C.T. Dunbar, wrote The Daily Province, “caused cold chills to run up and down the spinal column of would be acreage buyers” when he opened the bidding on two three-acre lots at a whopping $5000).

And then, in 1909, the measured growth which had characterized the decade thus far vanished, and the city — indeed, the entire province — descended into speculative insanity. The market explosion that followed was the result of several intersecting factors — chief among those, the crushing victory of Richard McBride’s Conservative government in the provincial legislature.

The party had been in power since 1903, and had spent years using free-market rhetoric to disguise their true intentions: advancing the interests of the financial elite. Chief among their allies were the wealthy speculators and rentier capitalists descending on the provincial housing market — most of them from Europe and the United States.

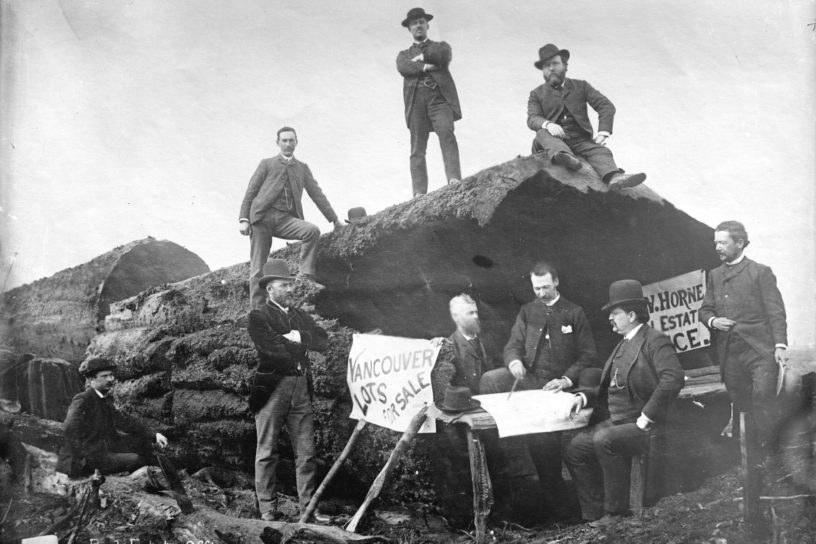

Russell and McCuaig Real Estate, circa 1900. From the City of Vancouver Archives

Even before 1909, the Conservatives had redrafted the provincial Land Act, allowing real estate professionals to get around government preemption limits by collecting land on behalf of others, and then reselling it (this required nothing more than a signature, and stories abounded of speculators buying beer for anyone who would sign a power of attorney form). The province, Attorney General William Bowser argued, would vehemently defend the “freedom of the speculator,” encouraging them to buy, sell, and hyper-inflate the value of land in an environment virtually free of oversight.

“The Government cannot control the investments the people wish to make any more than it can undertake to regulate the food that they eat or the clothes they wear,” Bowser claimed. “As matter of fact, these speculative waves come and go, and, especially on this coast, have succeeded each other many times […] When Governments dictate to the people what they shall buy and sell and how and at what prices, they will be about as successful as our ministerial friends in making everybody good according to their standard of goodness.”

And investors responded.

Between 1908 and 1913, the rate at which overseas capital flowed into BC real estate increased by a staggering 1,175 per cent — much of that focused around or within Vancouver. During this period, real-estate interests also managed to wrest back control of city council; between 1904 and 1915, they accounted for anywhere between thirty to fifty per cent of its aldermen. In 1909, the same year as the Conservatives took much of the legislature, Vancouver elected realtor Charles Stanford Douglas as its mayor, a man who, according to The World, “had accumulated property by fair means.”

By 1910, the city was home to more than six hundred real estate agents. By 1912, there would be more than one thousand — one for every hundred citizens. Overseas money poured in, encouraged by the wealthy and their enablers in government, as well as a series of local lending institutions set up chiefly to finance land deals (virtually all of these, including Dominion Stock and Bond Corporation, and Vancouver, Savings, Loan, Trust, and Guarantee Co, were operated by McBride MLAs or real estate developers like Henry Ceperly). A series of notable public buildings also took shape, including the provincial courthouse (later the Vancouver Art Gallery), the Birks Building and the Vancouver Block.

During the 1909–1913 period, speculator influence was so great that it even influenced the naming of major streets; in 1909, in hopes of encouraging American investors to purchase land near Westminster Avenue and Ninth Street, the city renamed them Main Street and Broadway, respectively.

In 1911, the CPR opened up Shaughnessy for development (but with specific covenants inserted to restrict ownership to solely the white and affluent). The first apartments began to appear in the West End, and prefab bungalows sprung up in Kitsilano. The city made thirteen million dollars in building permits during 1910 alone. By 1912, that number had grown to nineteen million. Naturally, land values had skyrocketed; a fifty-two-foot lot on Hastings, which sold for twenty-six thousand dollars in 1904, had jumped to ninety thousand dollars by 1908. By 1909, it was $175,000. In 1912, at a time when wages were roughly fifty cents an hour, a lot at the corner of Granville and Hastings sold for an incredible $725,000.

But, as was typical during the McBride years, these figures represented a gain for speculators, and a loss for locals. Theoretically, the government claimed, cheap land was available province-wide to anyone who wanted it, in the form of preemptions [property the government made available to settlers for a fraction of the cost, provided they lived and worked on the land] — of the sort that had allowed the Three Greenhorns to gain a foothold in the West End. But in reality, preemptor maps drawn up by the Department of Lands showed that the majority of that property had already been gobbled up by syndicates of investors from New York, Chicago, and London — syndicates in bed with the government, who had quietly bought the land at below-market rates.

Premier Richard McBride at the opening of Marine Drive, 1913. From the City of Vancouver Archives

By this time, many members of McBride’s government were also speculating themselves; Price Ellison, the aptly-named Finance Minister, was president of Dominion Stock and Bond, having worked a deal to buy land from the government at one dollar an acre, and sell it for almost forty dollars (using the profits to construct the Dominion Building — then the tallest building in the British Empire — which still stands today). A company run by Attorney General Bowser was up to its neck in land leases, and at one point, to keep up with payments, he introduced a bill in the legislature to artificially depress the value of his own property. By then, speculative mania had even descended down to the working class, and eager Vancouverites stretched themselves to the breaking point to cash in on the boom; according to a 1912 pamphlet entitled “The Crisis in B.C.” during a single week in October, more than forty per cent of the land-purchase applications received were from working class people.

“Great is the confidence of the participants — and the entire community participates,” wrote novelist Bertrand Sinclair, of the boom. “For the time being it is forgotten that whatever goes up must come down. It is a great game while it lasts. Better than draw poker. Better than playing the ponies. It is legitimate, respectable, as well as thrilling. It isn’t gambling. It isn’t even speculation. It is investment.”

The words of political economist Henry George on a billboard, 1890. From the City of Vancouver Archives

“We live in the land of destiny,” beamed one R.J. McDougall, in a 1911 issue of B.C. Magazine. “In the land of wealth where, though gold is not idly picked off the rocks or from the pavements in the streets, it is just as surely gained from the platted acres and twenty-footers around us. One day an artisan may put the scanty savings of a lifetime into a tiny holding out among the evergreens, and on the morrow almost, he is building city blocks from the proceeds thereof.”

For nearly four years, global capital flowed into the city, fuelling a cycle of rapid expansion, population growth, and a property market that had surged completely out of control. In 1912, at the height of the boom, McBride was elected for another term. But despite maintaining a cheery outlook in the press, there were many within the government who were beginning to worry about what might happen when the bubble burst.

“It was all a glorious daydream,” McBride’s personal secretary R.E. Gosnell later wrote, “from which I felt, sooner or later, we must awake to sterner realities.”

And awake they did.

“Warnings that the McBride empire rested on a base of loose sand, that real development was confused with speculative dreaming, that freedom had been established only for the speculator, that the fruits of the toil of workers were consumed by greedy buccaneers, were dismissed as the sour complaints of gloomy political pedlars,” historian Martin Robin later wrote. “Bowser, who cared little about the rule of law or the concept of justice, spoke for the speculator, the prevailing culture hero who pursued profit by utterly disregarding accepted rules, just as McBride was worshipped by the myriad of dreamers for his facile optimism, his capacity for ignoring rights and looking the other way.”

In 1913, a committee of British investors toured the western province, and they didn’t like what they saw. Further jarred by the crash of the US stock market, they, and many other speculators began to pull up stakes, and the result was catastrophic. McBride’s strategy, while giving the appearance of economic growth, had instead allowed speculative profits to replace actual labour and industry, and without those profits, both the economy and the housing market went into a tailspin.

Vancouver Real Estate Brochure, 1890. From the City of Vancouver Archives

Building permits, which had topped nineteen million dollars in 1912, plummeted to less than one million dollars by 1915. Government revenues fell by half. Commercial rents declined by fifty per cent, and the working-class investors who had tried to claw their way into the market were forced into bankruptcy. In 1914, Dominion Trust collapsed, leaving its more than five thousand creditors with nothing. The City of South Vancouver went into receivership.

By the winter of 1913, the city had spent $150,000 on unemployment relief, and construction had slowed to a virtual standstill. And in the wake of it, property values fell substantially; a corner lot on Cambie and Broadway, listed for ninety thousand dollars, eventually sold for less than eight thousand dollars.

People were “perceptibly poorer in pocket and prosperity and speculation got a terrible jar,” wrote R.E. Gosnell. “There was everything to sell and nothing to buy.”

The crash destroyed the Conservative government. In the aftermath, it was discovered that Attorney General Bowser, unable to meet his mortgage obligations, had introduced a bill which allowed his company to postpone their payments indefinitely. He had also helped Dominion Trust (run by Finance Minister Price Ellison) circumvent government banking regulations. Both Bowser and McBride had appointed siblings to lucrative government posts. In 1915, Ellison, Provincial Secretary H.E. Young, and Premier McBride himself all resigned in scandal.

The bubble had burst in a catastrophic way. The “Land of Destiny” had gone to ruin, the “scanty savings” of artisans long vanished, and for the moment, Vancouverites found themselves more firmly in the world of Henry George than R.J. MacDougall.

After five years of spectacular returns, the vacant lot wasn’t working. And the next few decades wouldn’t be easy.

Read more tales of Hidden Vancouver.