Dr. Kenneth Montague knew he wanted to collect art when he was only 10 years old. He was visiting the Detroit Institute of Arts with his family and came across a black-and-white photograph that captured, in monochrome glory, 1930s New York during the Harlem Renaissance. A Black couple, sharply dressed and draped in long raccoon fur coats, poses with a pristine Cadillac. Glamorous yet casual, they glance into the camera, coolly unbothered by its presence.

The evocative image by celebrated Harlem portrait photographer James Van Der Zee ignited a passion for Black-made art in Montague, a child of Jamaican immigrants living in Windsor, Ontario, who would grow up to be a successful dentist as well as an art collector. This passion would culminate in one of the largest privately owned collections of Black art in Canada. Montague’s Wedge Collection, which he began assembling in 1997, comprises more than 400 paintings, sculptures, and photographs by Black artists around the world.

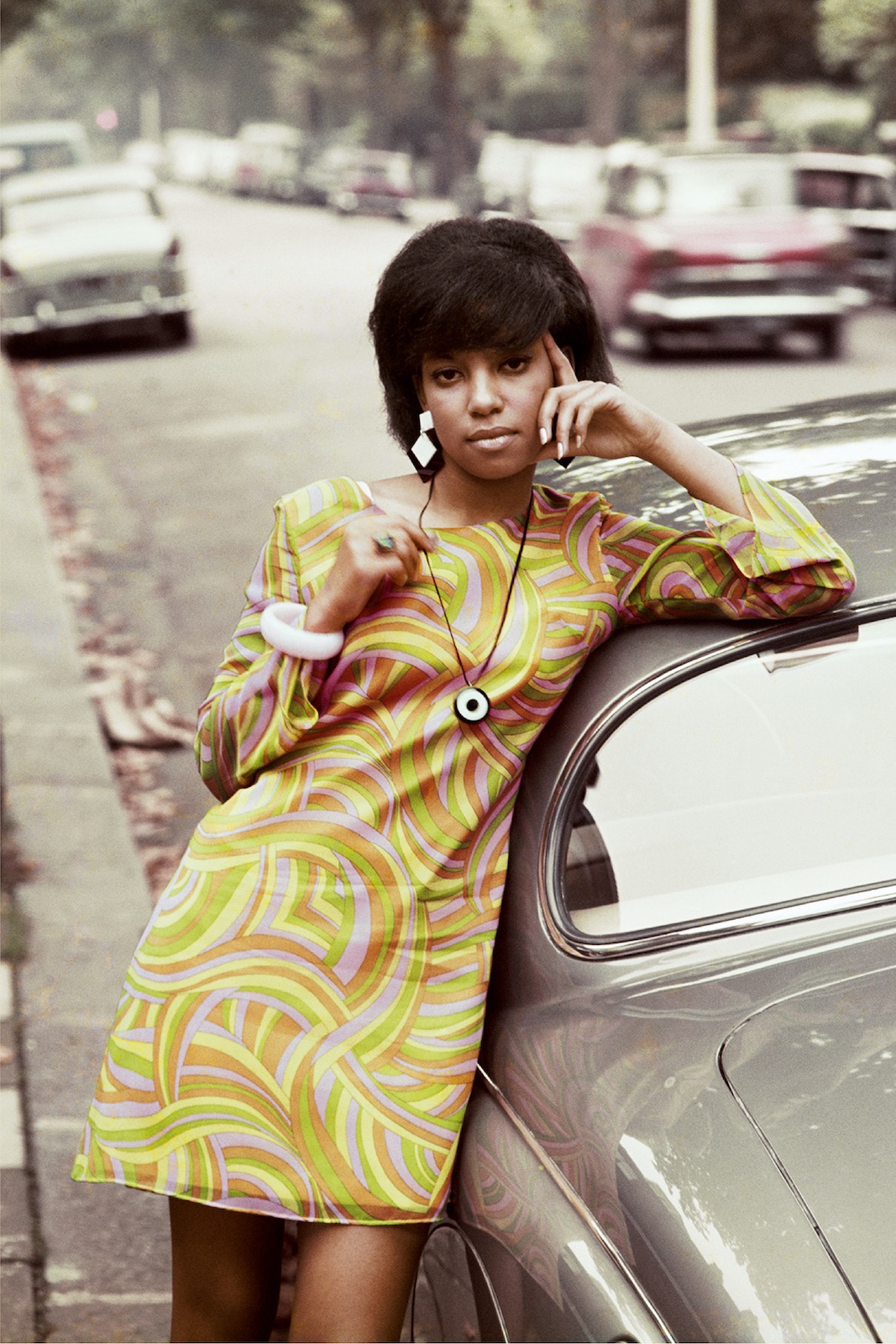

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London, 1966. Image courtesy of Autograph ABP.

Over 100 photographs from this collection were selected by curator Elliott Ramsey for the Polygon Gallery’s exhibition As We Rise: Photography From the Black Atlantic, including the image of the glamorous Harlem couple that started it all. The photographs, all by Black photographers, tell a nuanced story of Black experience, whether in the intimacy of a bedroom or under the lights of a studio. The exhibition’s title, As We Rise, comes from a maxim of Montague’s late father: lifting as we rise. “If you do well, you should love other people in your community,” Montague says. This exhibition is the artistic manifestation of those words. Works of Black artists stand side by side, speaking to each other, lifting each other up.

It’s not about oppression. It’s not about the typical kind of exploitative images around the Black community that you might see in newspapers.

“It’s about uplift,” the collector says of the exhibition’s intention. “It’s not about oppression. It’s not about the typical kind of exploitative images around the Black community that you might see in newspapers. Things like starvation and hunger and police oppression. This show is much more about the beauty of ordinary Black life.”

Dawit L. Petros, Hadenbes, 2005. Chromogenic print. Image courtesy of the artist/Bradley Ertaskiran.

Throughout this exhibition, that ordinary beauty unfolds like a family album. On its own, each photograph, taken in different time periods across the diaspora, tells a distinct story of Black identity. An identity as varied as the range of human emotion, from the fervour of a modern nightclub in an untitled image by Tayo Yannick Anton to the intimate vulnerability of a nude self-portrait by Texas Isaiah.

And yet, when viewed in sequence with the rest of the collection, these images become part of a larger story. Idiosyncratic characteristics become parallels in minute details: a gaze, a slant of body posture. American street photographer Jamel Shabazz’s portrait Best Friends, Brooklyn, New York, 1981, depicts two women standing in the subway, wearing matching blue blouses and white flared pants. The friends stand close to each other, leaning their bodies imperceptibly together. There’s an intimacy, an inside joke that only they understand.

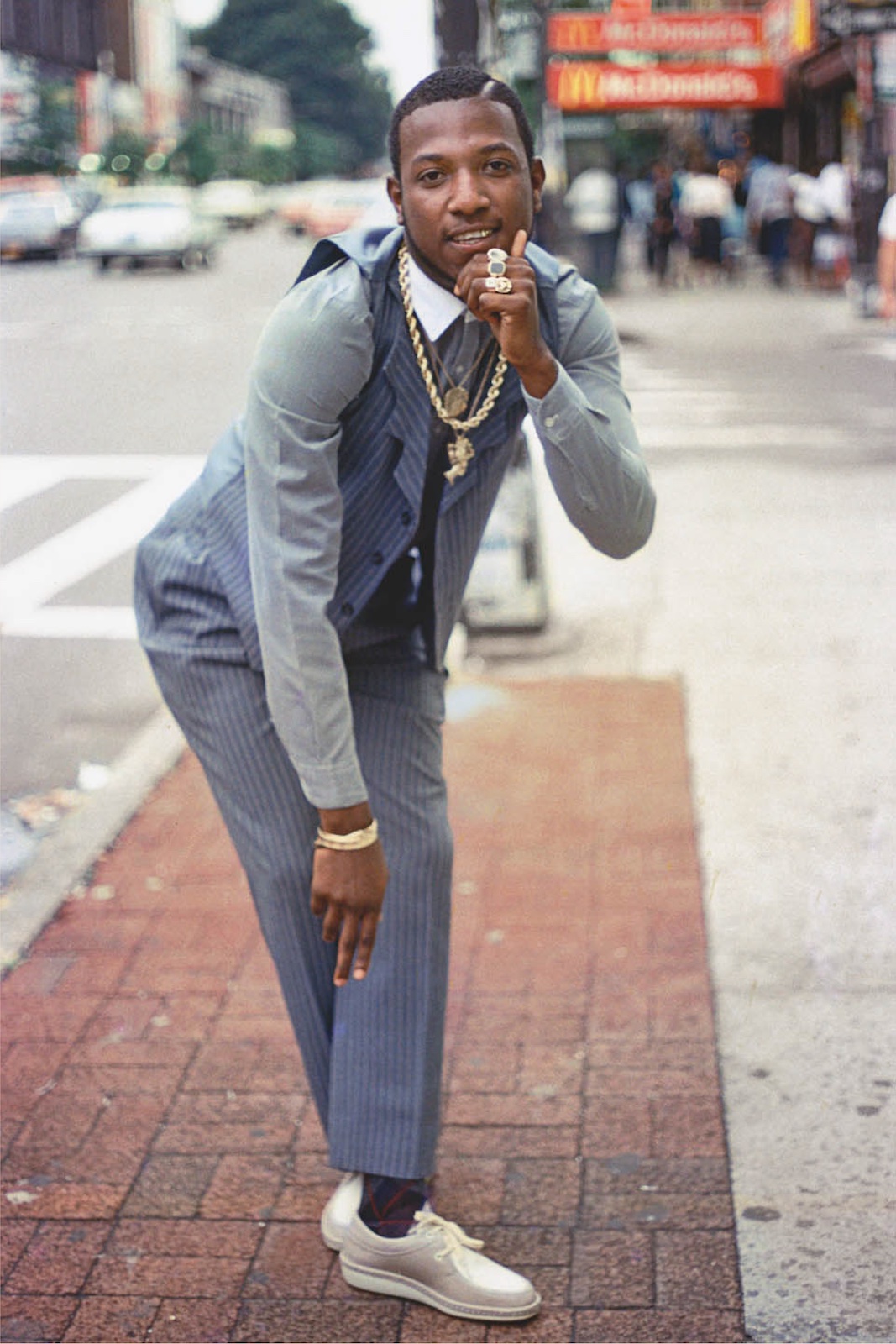

(Left) Samuel Fosso, ’70s Lifestyle, 1975–78. Gelatin silver print. Image © Samuel Fosso, courtesy of JM Patras/Paris. (Right) Jamel Shabazz, Best Friends, Brooklyn, New York, 1981. Chromogenic print. Image courtesy of the artist.

Meanwhile, exactly 40 years later, Canadian Jamaican photographer Jorian Charlton evokes a similar closeness in an untitled portrait of two women in pink outfits. Posed in the same squatting position with their upright backs to the camera, the women have their faces turned away. The viewer is kept in the dark, but in the exactitude of their matching poses, the women share a secret reminiscent of Shabazz’s earlier image.

Jamel Shabazz, Rude Boy, Brooklyn, New York, 1982. Chromogenic print. Image courtesy of the artist.

For Montague, a sense of personal camaraderie or familiarity between the viewer and the work is also integral to the exhibition. He sees echoes of his own childhood in a portrait by Dawit L. Petros featuring a family from Eritrea (where the artist was born) who have immigrated to Western Canada. “That family reminds me of my family. The white picket fence, all the tropes of the kind of comfortable suburban home in Canada, and yet, look at the family. You know they’ve had a different experience than maybe a lot of other Canadians,” he says, referring to his own experience growing up as one of the few Jamaican families in his city. In other portraits, we, too, might find echoes of our own lives.

Jorian Charlton, Untitled, 2021. Digital print on rag paper, mounted to alupane. Image courtesy of the artist.

Montague hopes Vancouver audiences, in particular, will walk away with a better understanding of the history of Black communities in this city. “There’s an important Black community in Vancouver. Hogan’s Alley has historically been a very important site in the journey of a lot of Black Americans who escaped enslavement and came through Canada,” he notes. This history is referenced directly in an 18-minute video art piece by artist Deanna Bowen, who recounts her own family’s migration from Alabama to British Columbia.

As We Rise is a celebration of Black existence, in all its multitudinous forms. “There’s many different ways of being Black,” says Montague, who hopes this exhibition will inspire more Black art collectors. “I think it’s particularly important for young audiences to see the richness and diversity in the Black community,” he adds. “Ultimately, I want to wedge Black artists into the story of contemporary art.”

The exhibit As We Rise: Photography From the Black Atlantic runs February 24 to May 21 at the Polygon Gallery. All photographs are from the book of the same name published by Aperture in 2021.

Read more from our Spring 2023 issue.