“What was it like growing up in Brooklyn?”

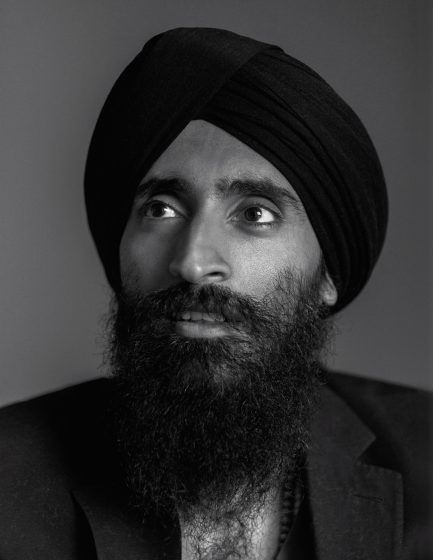

I ask Waris Ahluwalia my first question as he flips through a recent copy of MONTECRISTO.

“Let’s start with something better,” he says, without looking up.

I generally like to start interviews with some simple stuff, some pleasantries, before getting into the heart of it. But Ahluwalia called me on my soft question, and he was right: I did have a more interesting one. One that I had jotted down the night before, during Ahluwalia’s talk for Vancouver’s annual Indian Summer Festival. One that I was planning on asking when the two of us were more acquainted, but I guess it was as good a time as any.

“You started out as a club kid in New York, but you don’t drink or do drugs,” I say, referencing Ahluwalia’s early life as a teen at the epicentre of New York City’s now-legendary 1990s rave scene. “What was that like?”

Ahluwalia closes the magazine and looks at me. “I think there was something that I understood,” he says. “It in itself was all already new and exciting, so I didn’t need anything else—I didn’t need to be under the influence of anything else. It was already quite trippy. And I think the idea of the no drugs or anything is that I’m happy to be in a sense of awareness, of being where I am at that present time.”

It is difficult to describe Ahluwalia—his presence or his work. He is at once intimidating and encouraging, and it’s an alluring, enigmatic energy further complicated by his scrolling, impressive resume. His ‘90s club kid reputation quickly evolved into what can only be described as that of an international tastemaker. He is a luxury jewellery designer at his own company, an actor known for quirky roles in popular Wes Anderson films, and even, sometimes simply for being a Sikh man in the public eye, an activist. (He garnered international attention and outcry in early 2016 when he was banned from boarding an Aeromexico flight because he refused to remove his turban in public.)

Born in Punjab, India, Ahluwalia immigrated with his parents to the sleepy borough of Bay Ridge when he was five. The bustling streets of New York City became his backyard. Teenaged, turbaned, and sober as a judge, Ahluwalia was already so cool that he was easily accepted in the raucous ‘90s rave scene. “It was just a place to exchange ideas with likeminded people,” says Ahluwalia. “I didn’t realize it at the time, but New York, it was quite diverse. Everyone—you’ve got your club kids with your bankers—it was a mix.”

Serendipity, and Ahluwalia’s own hand, brought his diamond brass-knuckle design to glimmer in the face of a buyer at Maxfield in Los Angeles, spawning a spurt of purchases and a more rigorous delve into the world of jewellery design, entitled House of Waris. Its success can be denoted by its list of accolades, which include being a 2009 Council of Fashion Designers of America/Vogue Fashion Fund finalist, as well as collaborations with Forevermark and designer Benjamin Cho.

“Everyone can choose these things. I chose to live this life this way.”

Ahluwalia learned the business by doing. His first jewellery drawings were handed off to a connection in New York, who took them to a workshop where the manufacturing work was done behind closed doors. But while in Italy filming the modern classic film The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Ahluwalia connected with a goldsmith, looking to create a more authentic creation experience and product. “The other way just felt wrong, it wasn’t rocket science. I don’t live in falsehoods and that just felt false,” Ahluwalia says emphatically, his hands gracefully waving for emphasis. “Now I’m sitting off of Villa Giulia? Sitting with this goldsmith and his apprentice and we’re talking, sketching, and we’re drawing and having a human exchange? He’s the maker. And these are the ideas that I’m bringing. That felt right.”

Ahluwalia was brought into the whimsical world of Wes Anderson thanks to a happenstance encounter at a peace protest in New York. Shortly thereafter Anderson cast him in The Life Aquatic, joining a group of seasoned professionals including Bill Murray, Anjelica Huston, and Jeff Goldblum. “That was my first movie, and the question is usually, ‘Weren’t you scared?’ or, ‘What made you think you could do it?’” Ahluwalia says, as I silently congratulate myself for not posing those queries. “Wes didn’t ask me if I could do it—he just said, ‘Come to Italy, be in this film.’” Ahluwalia’s performance spurred roles in Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited and The Grand Budapest Hotel, as well as in non-Anderson productions like Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta’s Beeba Boys.

Ahluwalia’s life seems to be guided by providence. It is true that perhaps there is a spiritual docent moving small parts of his world, but Ahluwalia is unafraid to position himself towards the direction he wants to go in. “It wasn’t handed to me, it wasn’t given to me,” he says of where he is now. “I don’t want it to come off like, ‘And then I flew to Rome and met with a goldsmith!’ Everyone can choose these things. I chose to live this life this way. I chose not to take a job because I knew it was wrong. Most people know things are wrong but they still do them. They’ll say, ‘This isn’t for me, but I’ll still do it.’ You don’t have to do anything.”

We reach the end of our scheduled interview, and a publicist comes in to take Ahluwalia to be photographed. He invites me to join him, and even though I’ve asked all the questions I wanted to, I take him up on the offer. There’s just something about him, and everyone seems to agree.

Read the whole issue: get your copy now.