Ann Marie Fleming is describing the theme of her new full-length animated film, Window Horses: The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming, when suddenly her landline telephone rings. Startled, she gets up from the couch in her Vancouver living room and checks the name. “It’s my mom,” she says before apologizing for the interruption, quickly answering, and telling her mother that she has to call her back.

“My parents live in England,” Fleming explains as she sits down again.

It is mere poetic coincidence that she receives a call from her mother while discussing a film in which her protagonist is motherless. Window Horses tells the story of Rosie, a Chinese-Iranian girl raised by her grandparents after her mother is killed in a car accident and her father turns absentee. But more than that, the film is about shared cultures, about discovering new ideas and through that, discovering oneself.

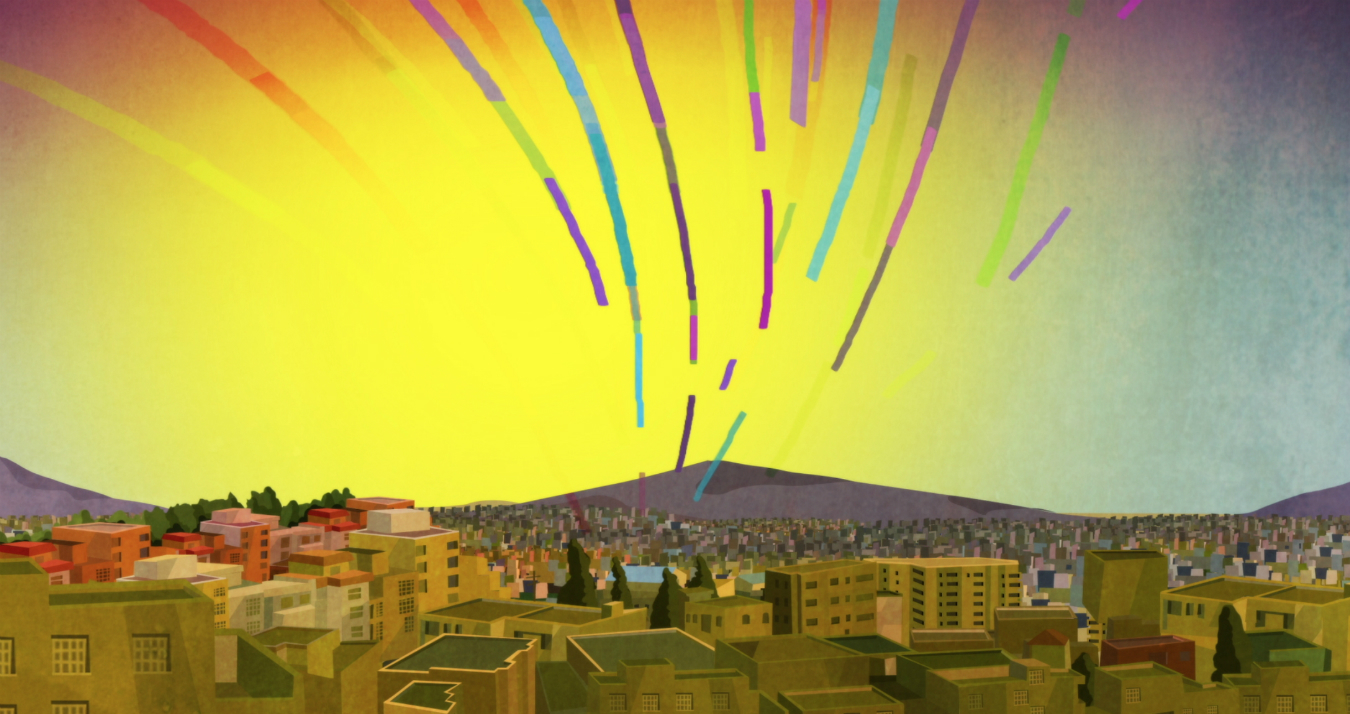

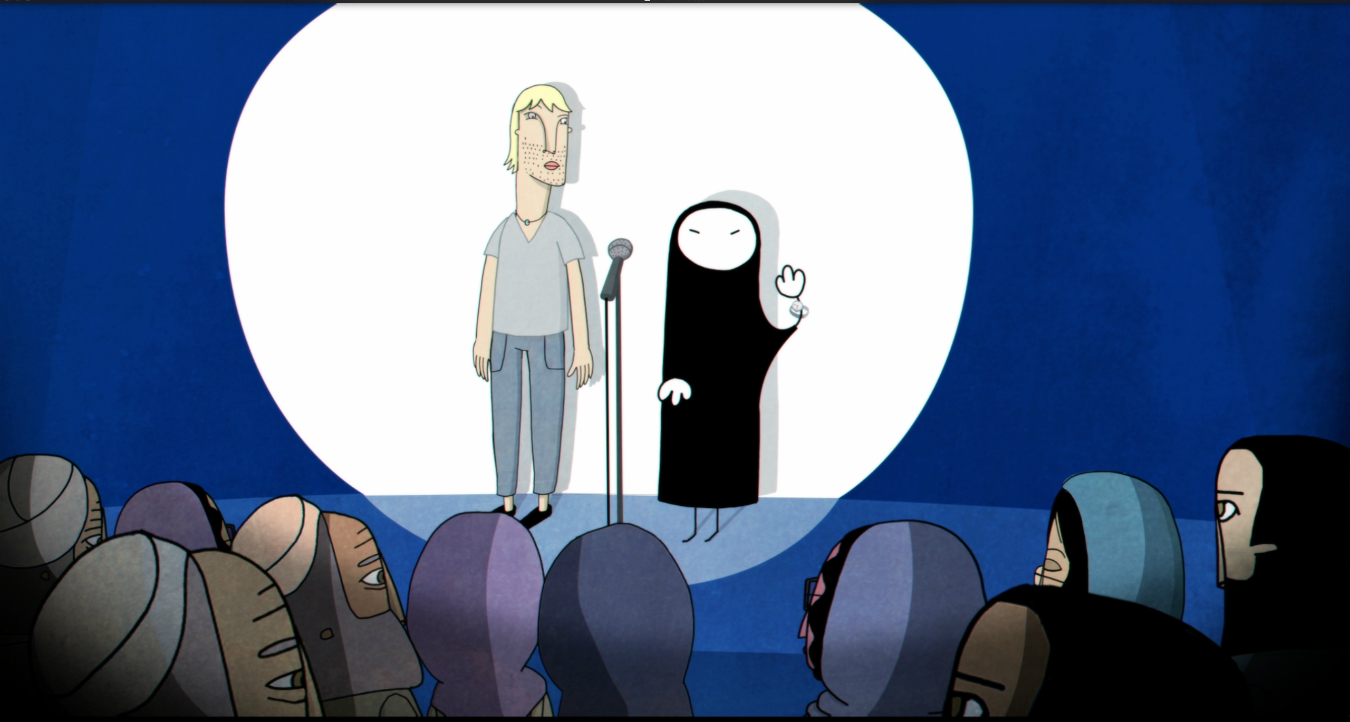

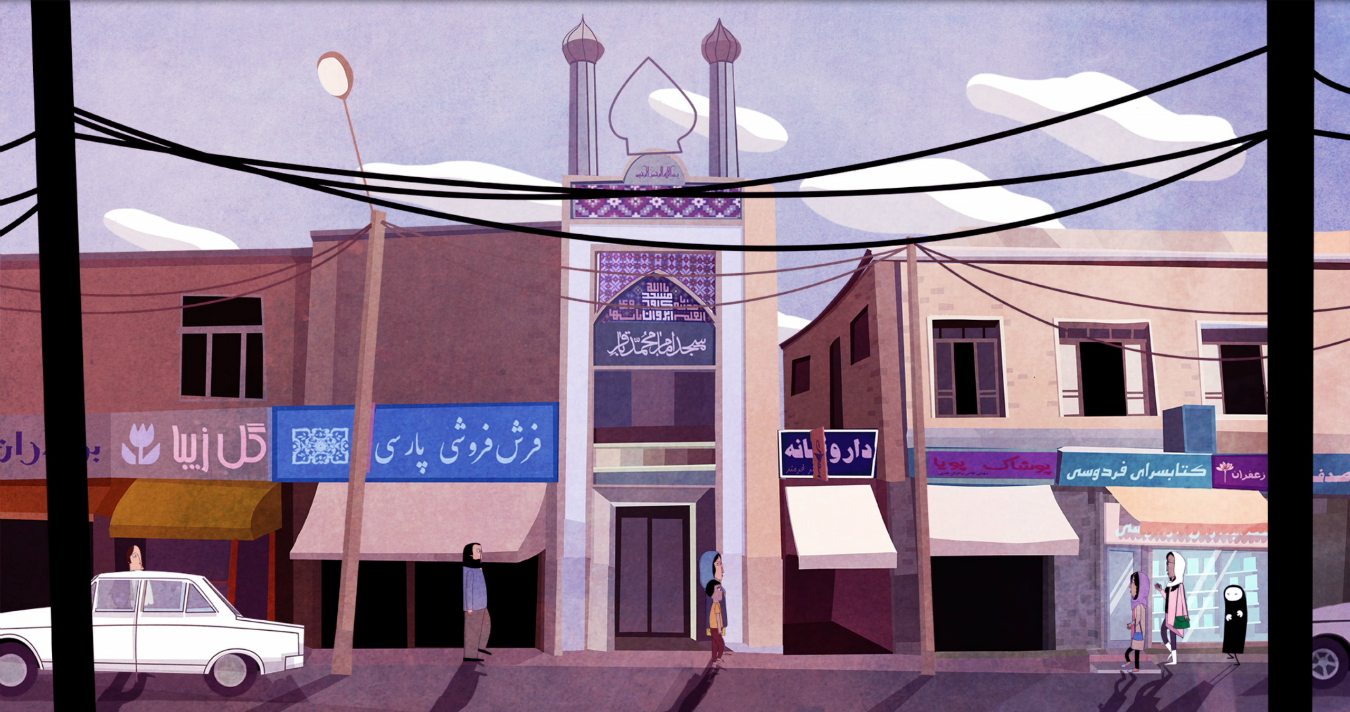

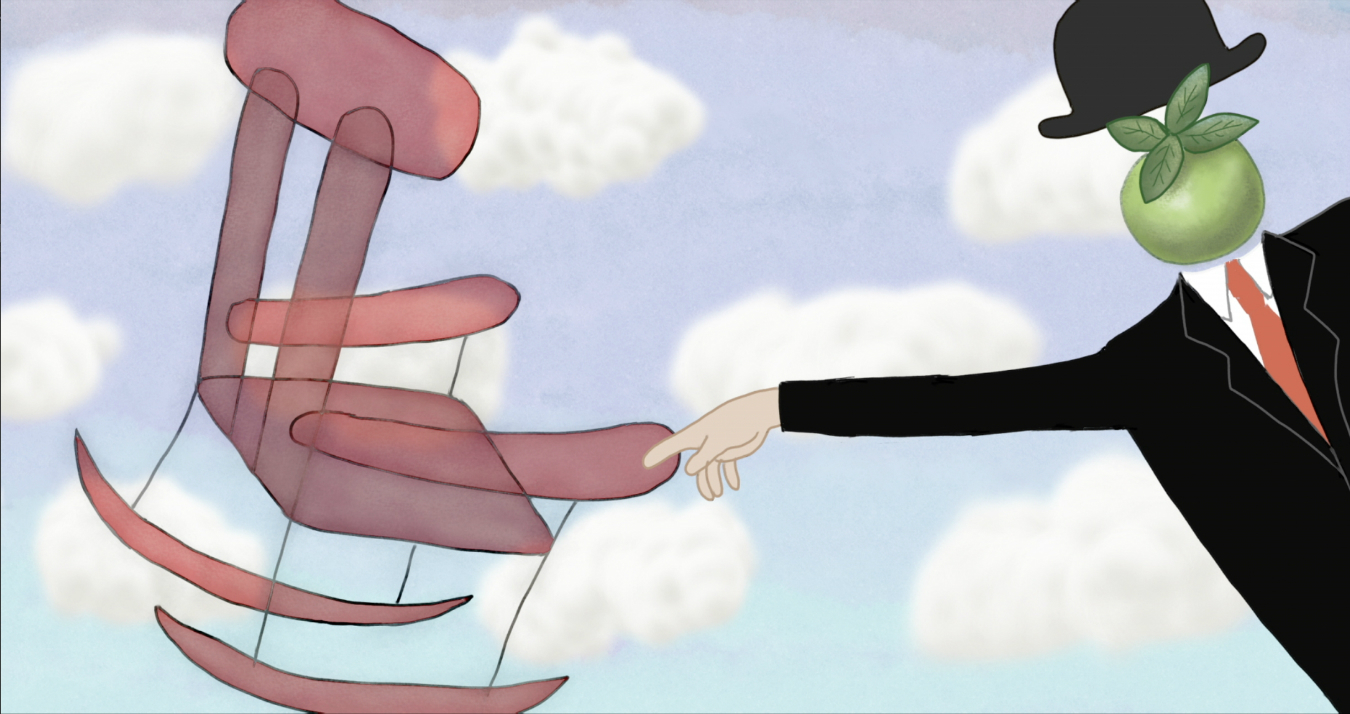

Rosie—voiced by Canadian icon Sandra Oh, who also acted as an executive producer—is a poet who dreams of travelling to Paris. But she finds herself instead visiting Iran after a poetry festival invites her to come and read. There, Rosie comes face-to-face with her family’s history, uncovering the truth about her father and learning the many shades of grey that are interspersed in both personal and societal dynamics. Playful, heartwarming, and at times uncomfortable, Window Horses uses the universal language of poetry to raise questions of identity, understanding, and even reality.

Fleming (The Magical Life of Long Tack Sam, The French Guy) is mixed-race like her character: with a Chinese mother and Australian father, Fleming grew up feeling misplaced in either culture. Born in China but immigrating to Canada when she was a child, she felt different both at home and in society. “I was just really tall and really white and didn’t speak Chinese—I spoke Chinese when I was in Hong Kong, but it never continued here, my mom didn’t speak Chinese to me. So I was an outsider in my family and then I was an outsider in this culture,” she recalls between sips of tea and nibbles of banana bread. “I was privy to what people said about Chinese people, what people said about outsiders, because they felt safe saying it around me; maybe they wouldn’t have said it around me if I was more obviously Chinese, Chinese-y looking. So I got this very strange taste of what things were like. I’ve always felt like an observer. That’s certainly where my point of view comes from and it’s certainly where my interest is.”

But will Window Horses show in the country where it is based? “I don’t know,” she admits. “It would be kind of fun if it was. But it’s a little nerve-wracking.” Fleming recalls speaking with an Iranian radio station during the Toronto International Film Festival and learning that people were talking about her film in Iran, comparing it to other negative outsider depictions. “Whenever I hear that I get all kind of butterfly-y,” she says. “I just want to say, ‘No, no, if you watch it you’ll understand!’” Indeed, Window Horses—co-produced by the National Film Board of Canada—celebrates Iranians and Iran, divulging the many nuances of such a storied and deep culture.

“The story is really simple: it’s just a family story, and Iran is a beautiful culture that we’re uncovering here,” explains Fleming. “All of this is just a delivery system for what I think is just really important right now: that we have to, it sounds so banal, but we all have to act like one family—globally we have to act like one family. We have to recognize each other’s differences and celebrate what we share together. We need compassion, layers and layers and layers of compassion, all over the place. Talking about the film, everybody goes, ‘Oh, it’s pretty timely now.’ But this message has always been timely, it’s always necessary.”

Overall, Fleming wants her film to be a teaching tool, a connecting link. Maybe it will open someone’s eyes, or send someone else’s closed with the soothing and mystical sounds of a poem. “I hope that people who would never see this film will see the film: people who are not interested in Iran, people who are not interested in poetry, people who are not interested in animation,” Fleming says. “I hope they find it and it changes them. I had this five-year-old kid come see the film in Portland—it’s not for children, but some really young people have seen it—he came out of it wanting to read Rumi.”

Read more about film.