The art market depends on the concept, or reality, of scarcity. One-of-a-kind, tangible “masterpieces” created by Picasso, Rothko, or Koons drive art auctions to million-dollar heights. Yet a quick Google image search of these same auction items reveals thousands of results. We’re taught that the physical copy, the original, is worth a fortune—yet its likeness, its digital existence, is penniless.

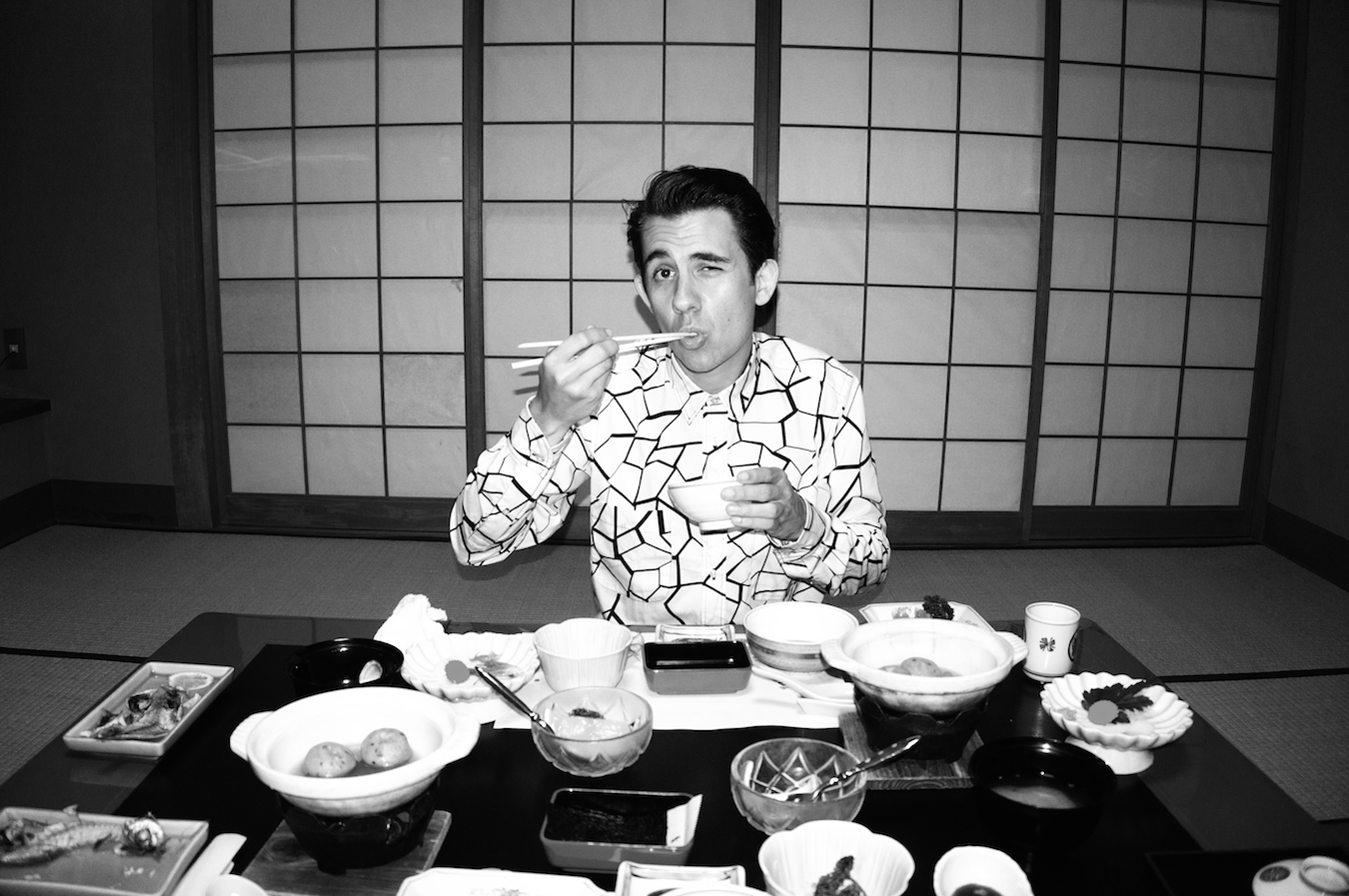

If rarity is what we value, how does one assess work without an original? It’s a question that new media and digital artists like Rafaël Rozendaal have been both directly and indirectly addressing. Rozendaal, who creates internet-based art and objects, has been credited as a pioneer in the now institutionally and financially credible medium of web-based art.

Rozendaal began his online career creating website-specific work on purchased domains. Early pieces such as 2002’s i am very very sorry .com and we will attack .com display simple animations paired with basic interactive features, relating to the very beginnings of the internet. “When I was in art school, I was working with video and animation and I was wondering, ‘How I could put that online?’” reflects Rozendaal, talking over the phone from his studio in New York City. “And I noticed that it’s really hard to put animations online, but I can make specific works for the internet that are smaller in file size and take advantage of being on a computer and not a TV. So you make something different.”

Born on and created for the internet, Rozendaal’s animations remain true to the democratic open source roots of the web. The links are free to be disseminated and shared; these site names, which double as the titles of the works, act as place holders, as well, ensuring as much permanency as can be afforded on the internet. “I like the idea of putting in a domain name and then it feels definitive and it will always be in that place,” he says. ”You will always know where it is and where you can find it.” Through the purchasing of the domains, each one required to be unique, Rozendaal has also identified and capitalized on the one item on the internet that cannot be reproduced. Though these works are free to view, Rozendaal sells the actual domains as the art pieces that are available for ownership. A contract outlined on his site reviews the specifics of owning a web-based Rozendaal, which includes the buyer annually renewing the domain name to ensure accessibility for the public. In reciprocation, the artist will credit the purchaser whenever the piece is included in shows or publications. Ownership here has no physical transfer, but rather is defined by an exchange of responsibilities.

“When I was in art school, I was working with video and animation and I was wondering, ‘How I could put that online?’”

Since 2002, Rozendaal’s career has moved beyond the desktop. Exhibitions around the globe including shows at Steve Turner in Los Angeles, Upstream in Amsterdam, and Postmasters in New York have brought Rozendaal’s work into the physical sphere, and with that, a few challenges. “I have a hard time understanding phenomenology,” he explains of this transition. “When I make installations, my first instant is to project the work; I think projection fits the lightness of the medium.” But he has found other representations as well. “I started playing with mirrors,” he explains. “If you’re working with light then you multiply the light, and now the screens are getting bigger and bigger so you don’t have to darken the space. It’s constant research for me, and it’s constantly changing.” Lenticular prints, video, and, most recently, woven textiles, have come to represent, or redefine, Rozendaal’s work.

Iterations of his offline art include taking over the dozens of screens that light up Times Square from 11:57 to midnight with his piece, much better than this .com. The work, which depicts two people kissing on loop, is sweet and touching while retaining its early internet aesthetic. “I proposed to do a kissing animation in Times Square because it’s so relatable and instant,” says Rozendaal. “I also like that it’s a really slow work, so it kind of slowed down Times Square for a moment.”

Online, however, Rozendaal’s output has become increasingly abstract. A recent example, blank windows .com, presents a collage of white, unadorned web windows will basic click and drag features. As his work approaches a more and more minimal aesthetic, new considerations arise. Moving the empty tabs in blank windows .com feels almost instinctual—highlighting the frequency, and monotony, with which so many of us encounter digital screens. It makes one wonder: what was the original website, anyway? Google it.

More from our Arts section.