The Vancouver Police Museum has a skeleton in its closet. Literally.

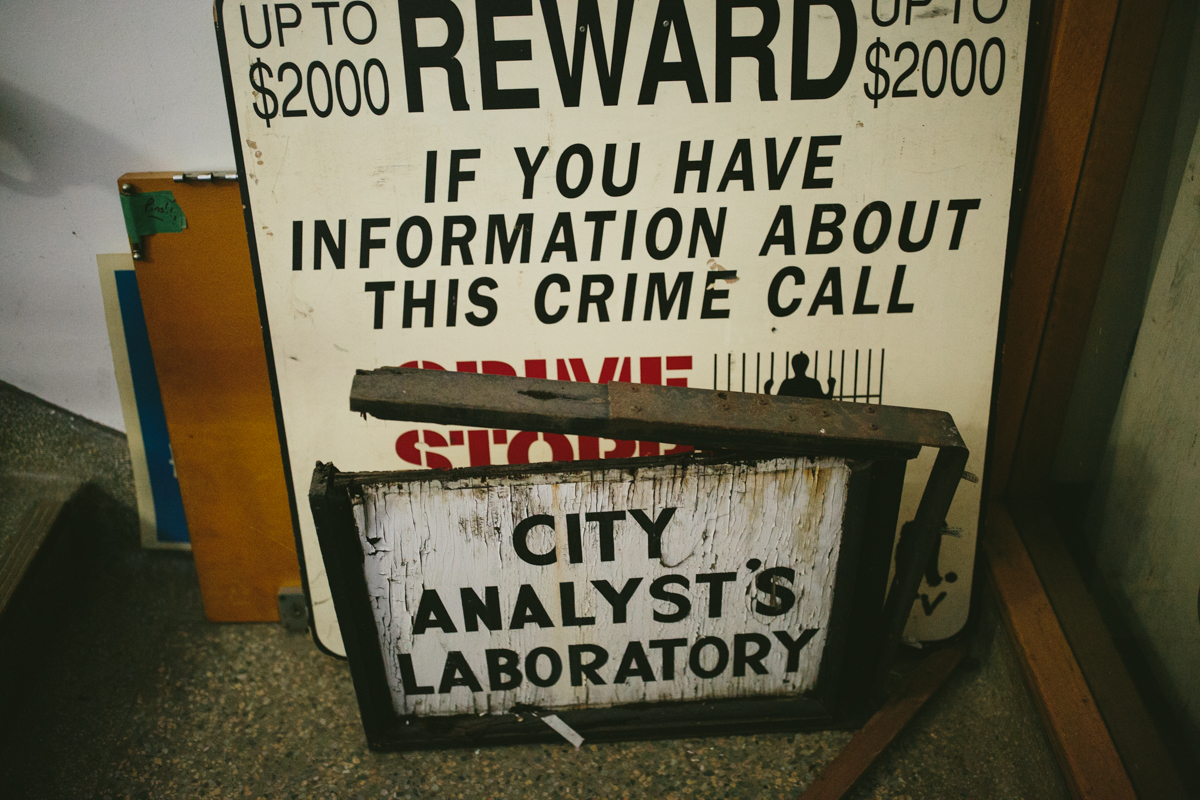

But that’s far from the only secret to be found in the 90-year-old building. While the museum itself opened in 1986, the bottom three floors of the facility—the former site of the City Analyst’s Lab, Coroner’s Court, and Overflow Morgue—have remained sealed to the public for more than 20 years, and have since become home to an assortment of discoveries that give a fascinating glimpse into a bygone era.

“Most museums don’t allow the general public into their storage areas,” notes Rosslyn Shipp, the museum’s then-director, as she carefully shows us around in 2017. “Also, it’s a really unique space, and there are some safety concerns, and not everyone knows what those are. It’s a city-owned building, and one of the conditions of us using the facility was that only the top floor would be accessible to the public.”

While the museum bustles away upstairs, featuring exhibits on everything from gangs to famous murders to youth and the law (full disclosure: this author helped research that one), the bottom floors silently house the remainder of the institution’s collection, including weapons, glass-plate negatives, and criminology equipment from through the ages.

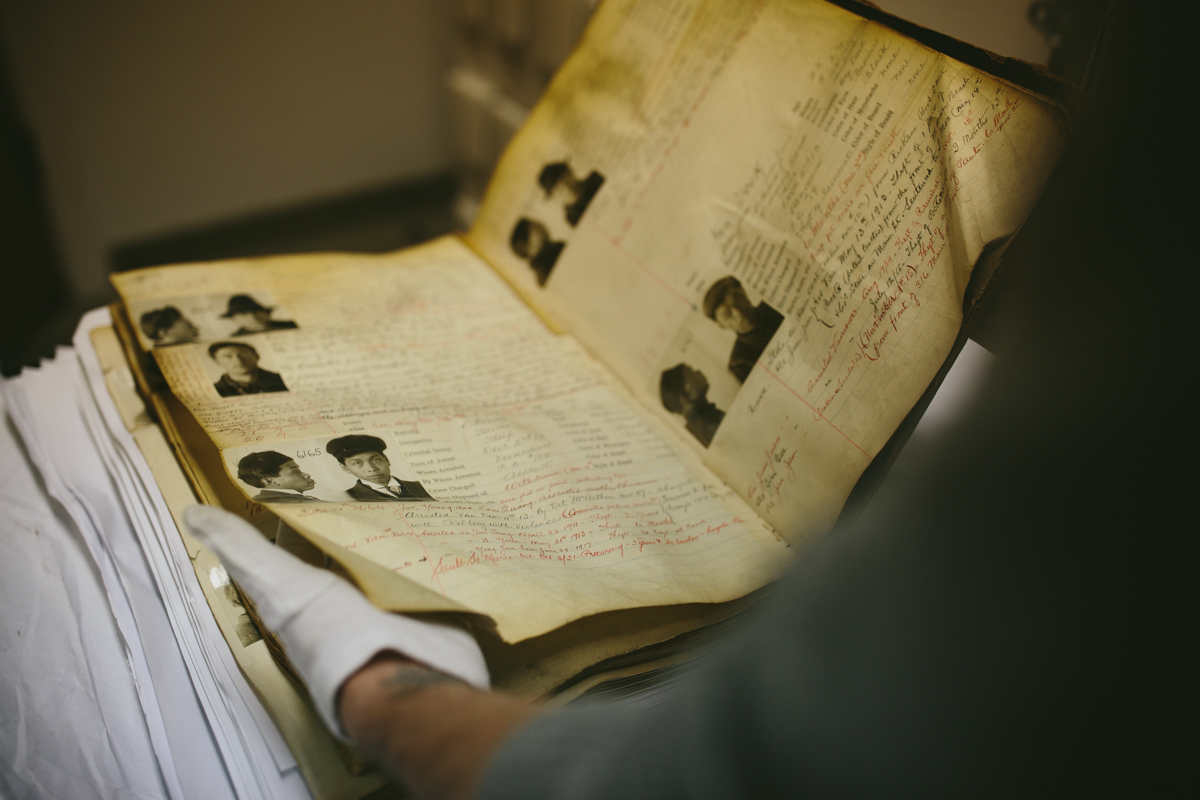

Hand-painted letters still adorn frosted glass doors like something out of a Raymond Chandler novel, and a century of annual reports, procedural manuals, and books on crime fill the shelves. Open any cupboard or drawer, and you’re liable to find a wide assortment of abandoned chemicals. Shelves still hold piles of antique glassware, a hint about the forensic techniques of yesteryear. Behind an iron door is a vault containing thick, bound books of antique mugshots.

There’s the former Overflow Morgue and “Blood-Drying Room;” there’s a steel door from an old jail cell, and a locked room filled with service weapons (even we weren’t allowed in there); and there’s ancient signage advising that “Safe Work Habits Reveal The True Craftsman.” And of course, there’s the aforementioned skeleton: human, and kept in a locked, stand-up cabinet. “We don’t have a lot of information,” Shipp says, “but as far as we know, she was an Asian female. When it comes to these kind of demonstration skeletons, the origins aren’t always clear.”

The City Analyst’s Lab first opened its doors in 1932, tasked with undertaking forensic testing for the police department—in particular, analysis of blood, bodily fluids, and toxicology. Over the years, it was home to a number of eccentric personalities, including coroner Glen McDonald (a renowned drinker whose autobiography contains a number of exaggerated stories) and John Vance, an internationally renowned forensic scientist who the Vancouver Sun once called “the single greatest deterrent to crime that the city has ever known.”

Vance’s work was so successful that he was regularly referred to as Vancouver’s “Sherlock Holmes,” and at least six attempts were made on his life.

The lab has also housed countless other workers and technicians over the years—one even in the literal sense. “We recently met a gentleman who used to work as a morgue tech, and he lived in a room down here for a few months,” Shipp laughs. “He actually lived here; it was only for a short period of time, back in the late ‘60s, but he made a wall of paper towel and toilet paper, and made a bed for himself. He later went on to be a medical examiner in San Francisco. And he said, ‘Oh yeah, I can always tell when the morgue is being used as a location in movies or TV. See that dent right here? It’s from when Glen McDonald threw a bottle of whiskey at my head.’”

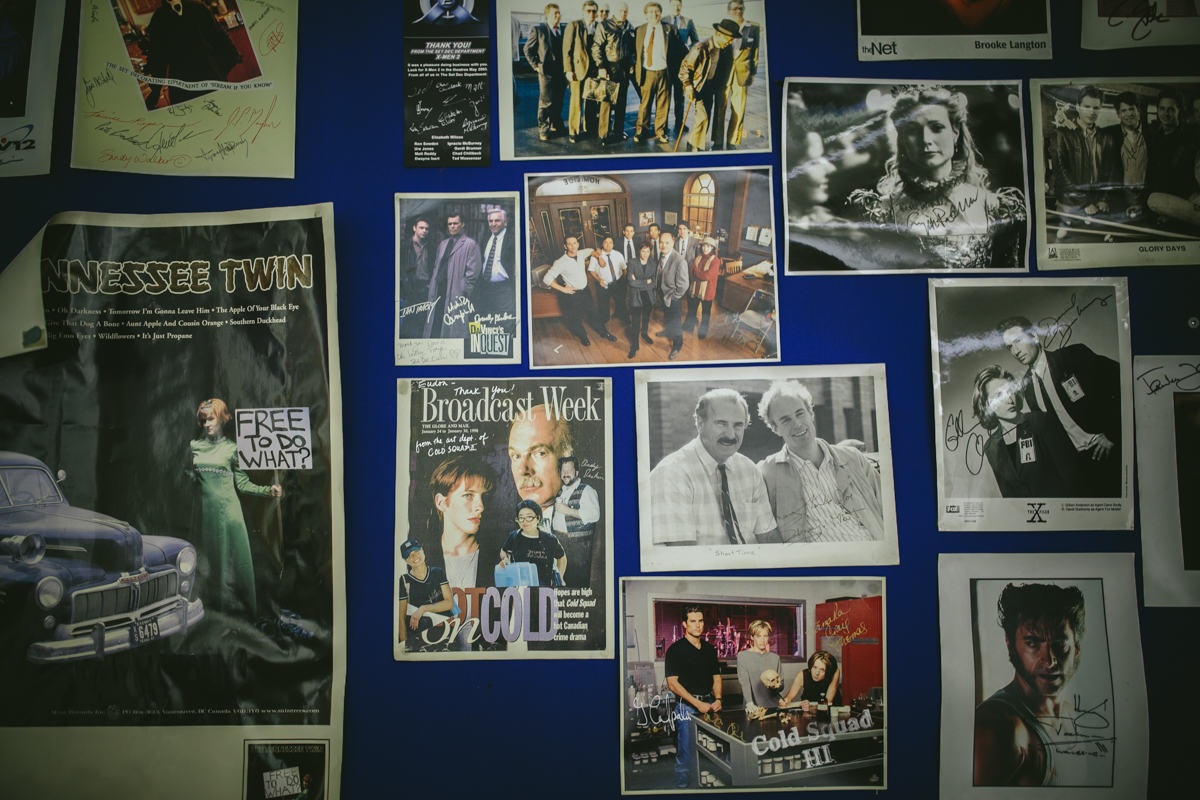

While the Coroner’s Court moved out in 1980, the Analyst’s Lab remained—underneath the functioning museum—until 1996, when its operations were decentralized. In the interim, it was used as a filming location for such shows as Cold Squad, The X-Files, and Da Vinci’s Inquest.

Today, the Vancouver Police Museum is one of the few institutions of its kind that functions without any direct involvement from the city or the police department; it’s kept alive through grants, a dedicated team of staff and volunteers, in-kind support (the city provides the building, for example), and donations.

These days, the lower floors are seen even less often by the general public; in contrast to past decades, filming is kept to a minimum—something both Shipp and the city support. And as the collection expands, as annual reports are filed away, as antique books are packed into paper and boxes into temperature-controlled rooms, the character of the former Coroner’s Court is changing rapidly. But for now, for those lucky enough to see it, it’s a fascinating glimpse into an era of police work long since past—and the eclectic cast of characters tasked with speaking on behalf of the dead.

“People come in expecting the morgue to be this weird, creepy, scary place,” Shipp says, “but I feel like it was more of a family atmosphere. There was a real sense that they were trying to tell the stories of those who couldn’t tell them themselves. The coroner worked in conjunction with the morgue staff, the pathologist; and the Analyst’s Lab was right below, the police station was next door. There was this beautiful symmetry that happened between the organizations. And that’s something that’s been lost today.”

This story from our archives was originally published on May 1, 2017, and updated on May 3, 2021. Read more stories of Hidden Vancouver.