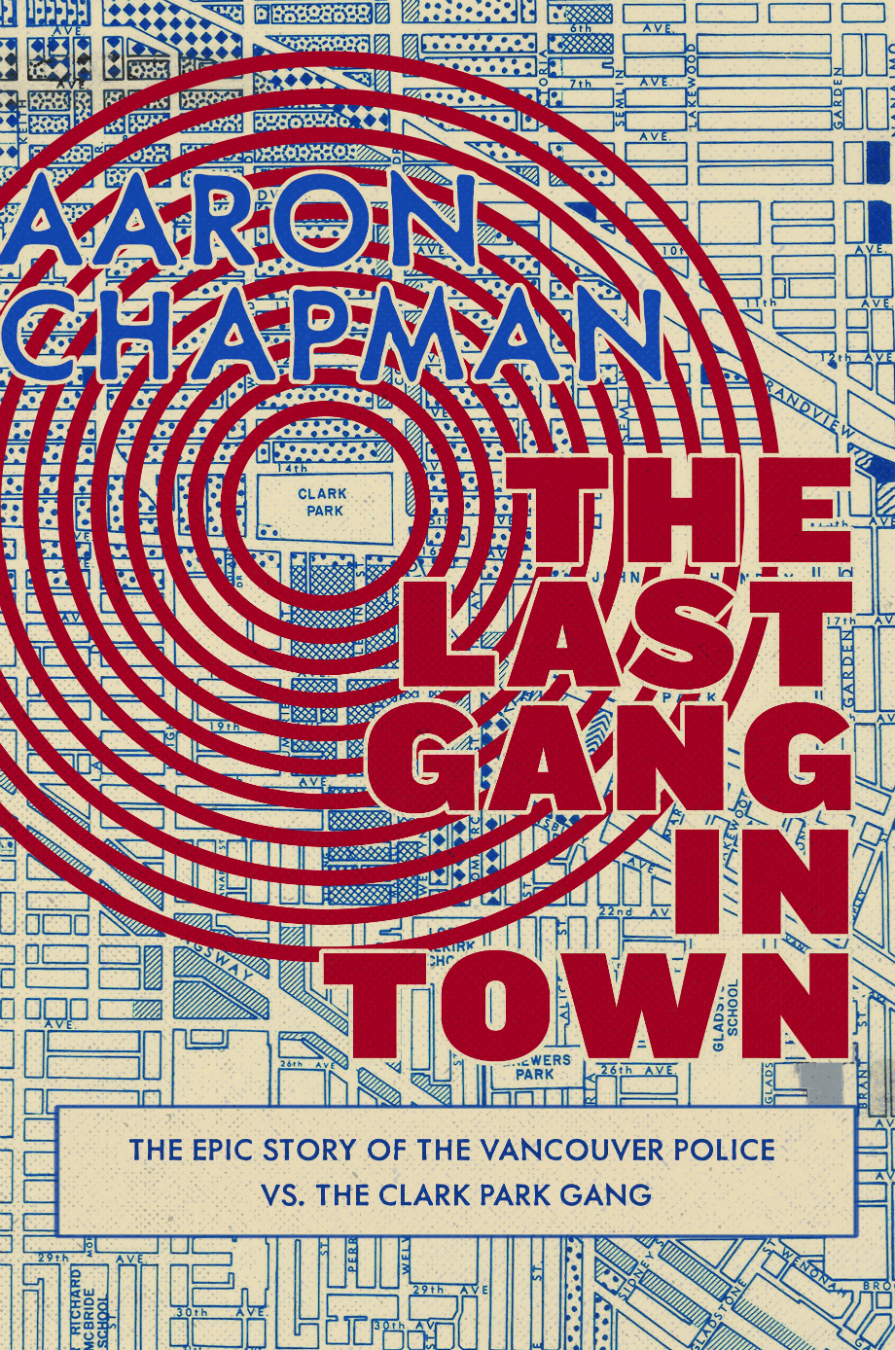

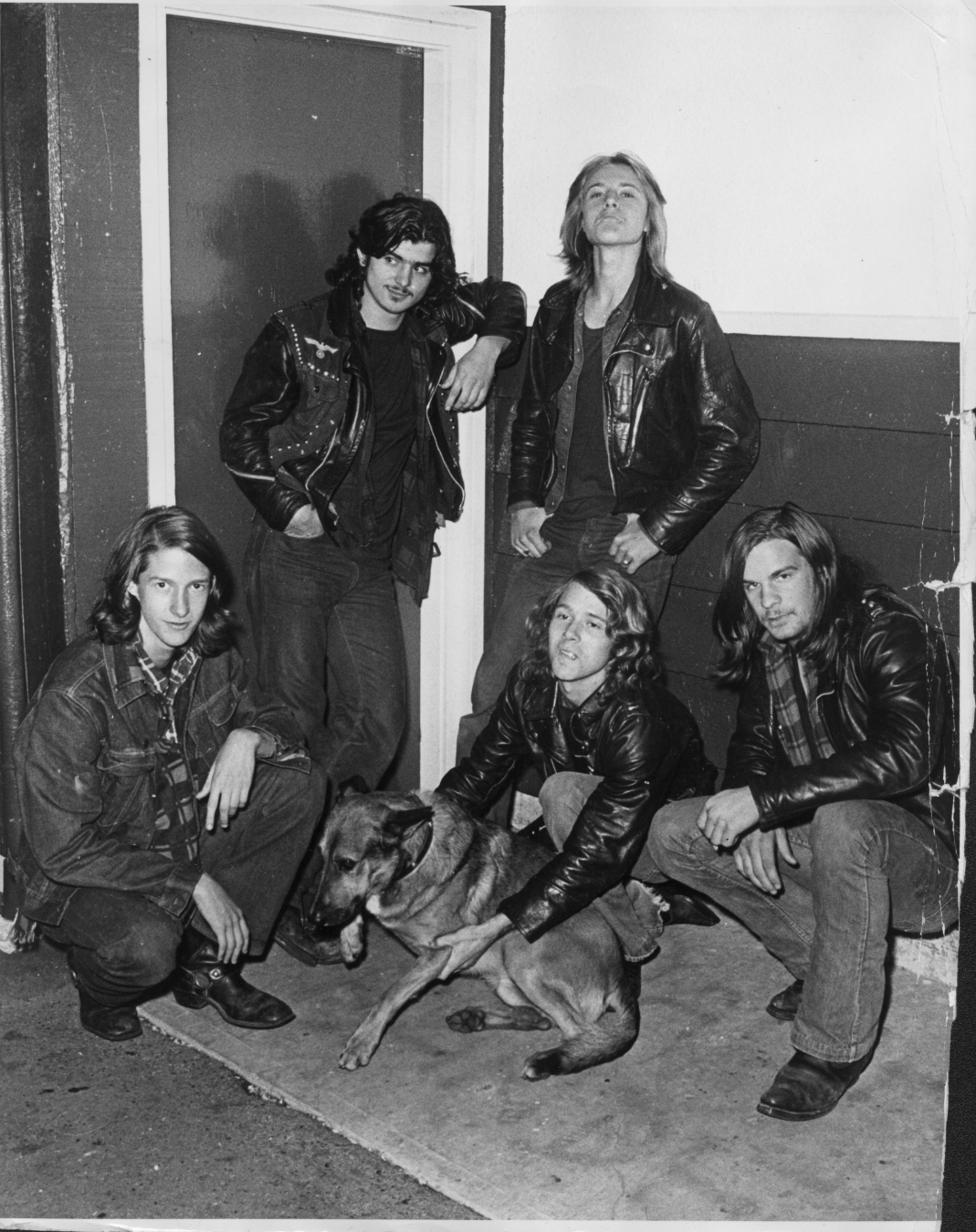

Vancouver still suffers from gang crime—from drug trafficking to targeted shootings—but local historian and author Aaron Chapman theorizes that it’s easier for regular folk to steer clear of that kind of clustered activity these days than the brazen, in-your-face approach of the youth gangs from the 1960s and ’70s. Chapman’s latest book, The Last Gang in Town (out now on Arsenal Pulp Press), explains how hundreds of East End kids from low-income backgrounds and troubled family dynamics locked down in spaces like Riley Park and Brewers Park at night to hold their territory, putting the scare into outsiders that dared crossed their greenways. While today it’s just as likely to find million-dollar properties in East Van as it is in Kerrisdale, Chapman notes that back then the East Side was a “hard scrabble place,” and no group was more feared on the turf than the Clark Park Gang.

“Everybody talked about how the Clark Park Gang was the toughest, the meanest, the most evil of all those people,” Chapman explains, noting that even growing up in town in the ’80s left him with a head full of violent hearsay about the crew. “The gang were like a bit of a boogieman, a ghost story that you’d tell kids: ‘Watch out! Don’t go out to East Van at this time of night or the Clark Park gang will get you!’ That myth fascinated me. I wanted to get the truth out of the myth.”

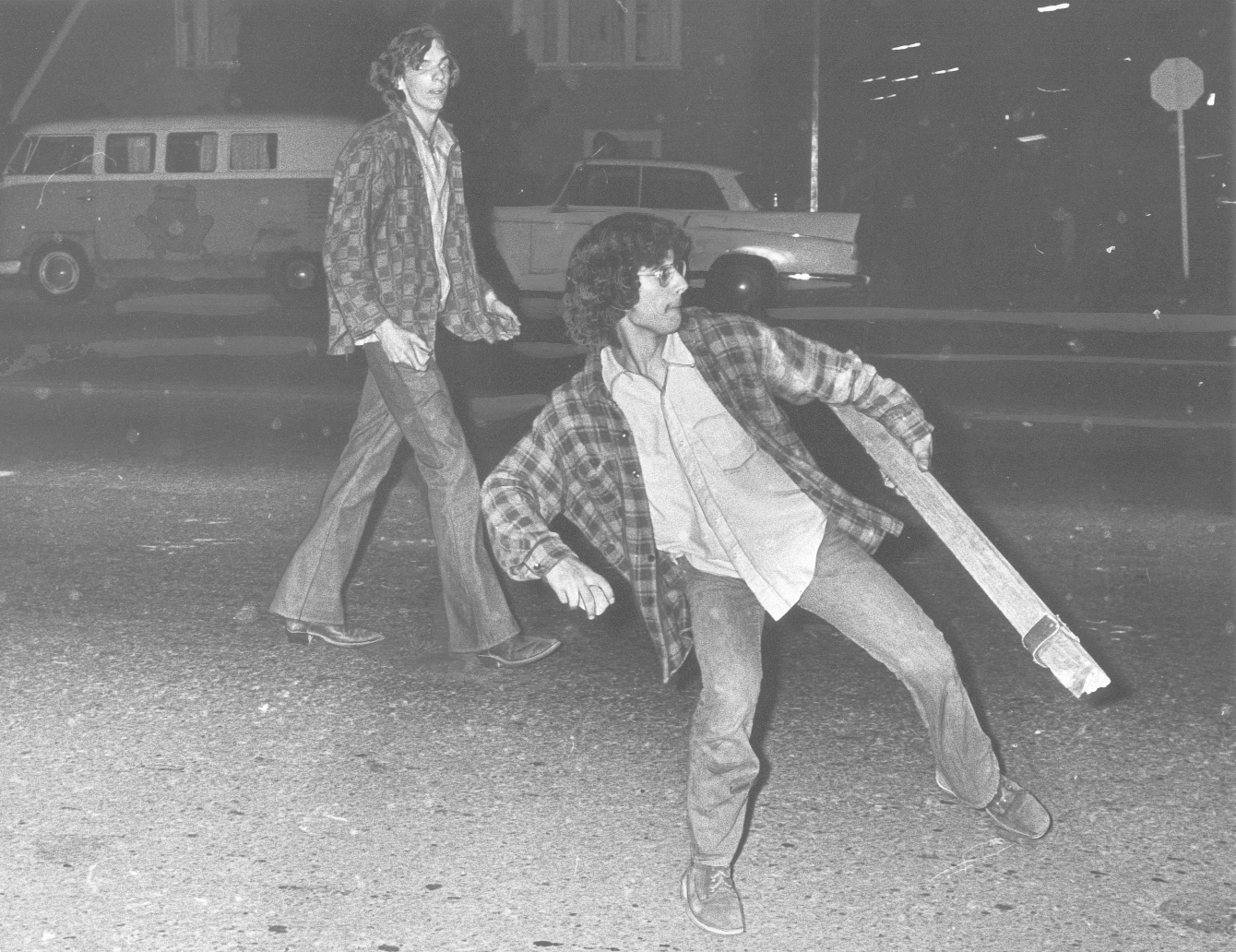

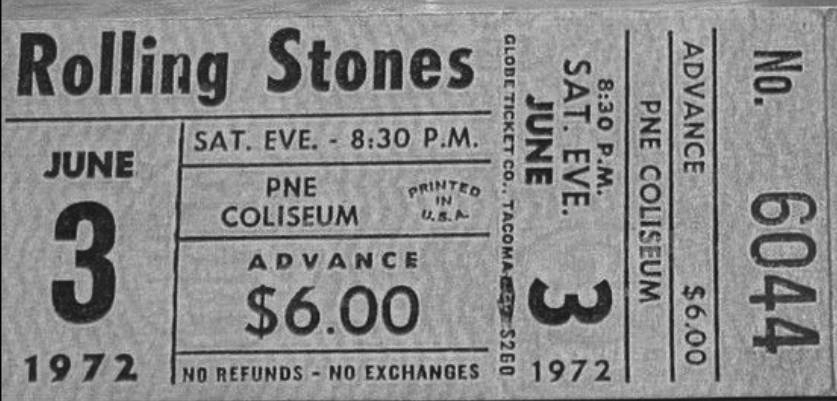

Chapman’s professional interest in the Clark Parkers stems from a 2011 Vancouver Courier piece that dealt with their legacy—a legacy raised sky-high because the gang was blamed for a Molotov cocktail-tossing brawl with police outside of a Rolling Stones concert at the Pacific Coliseum in 1972. The Last Gang in Town breaks down how the Clark Parkers were more of an apolitical, fists-up kind of force to be reckoned with: a crew of over 200 that were bouncing in and out of the juvenile detention system after dabbling in street violence, vandalism, arson, and theft. The book also examines the tragic police shooting of 17-year-old gang member Danny Teece, who had been escaping a stolen car with a few other boys from the group when he was killed.

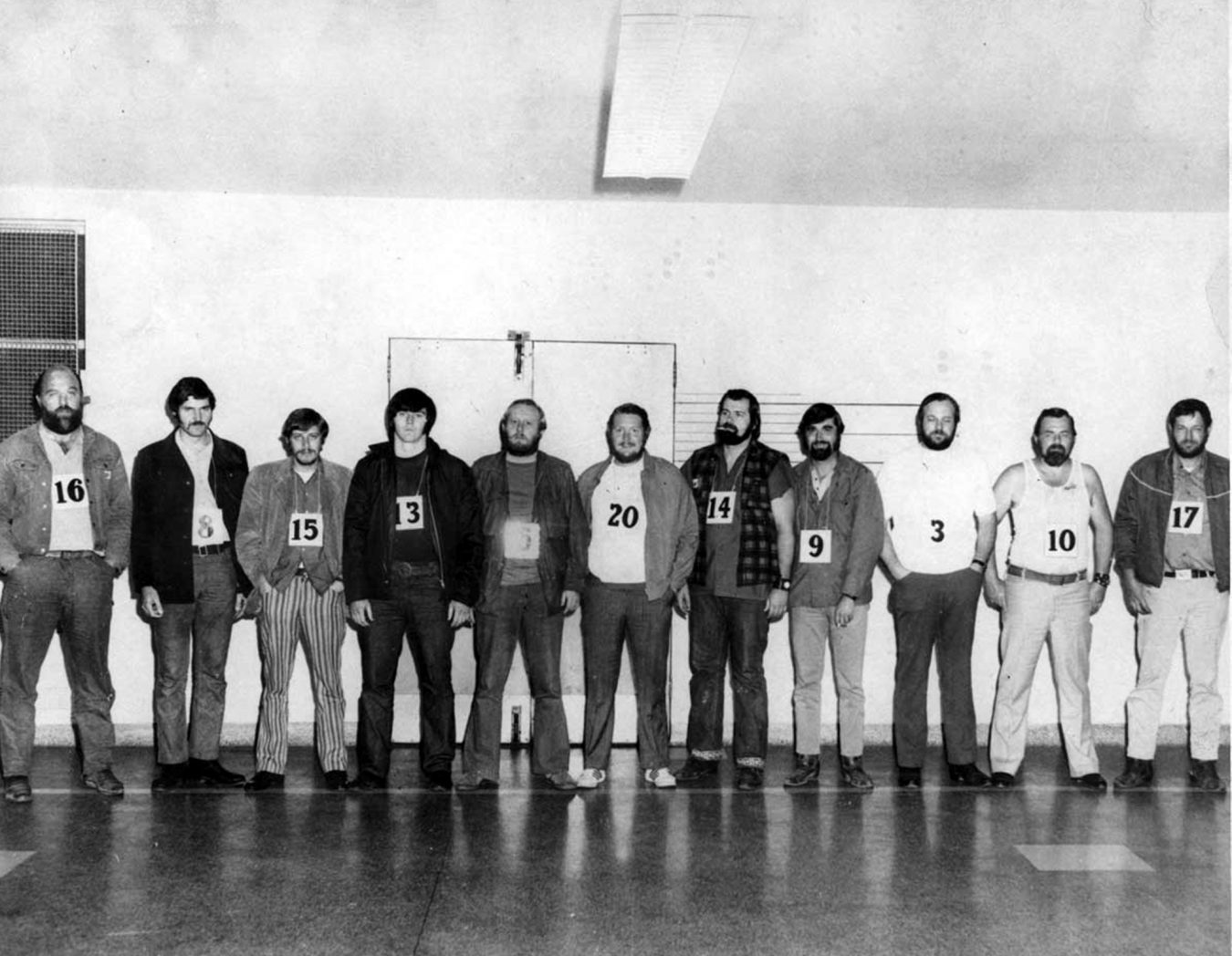

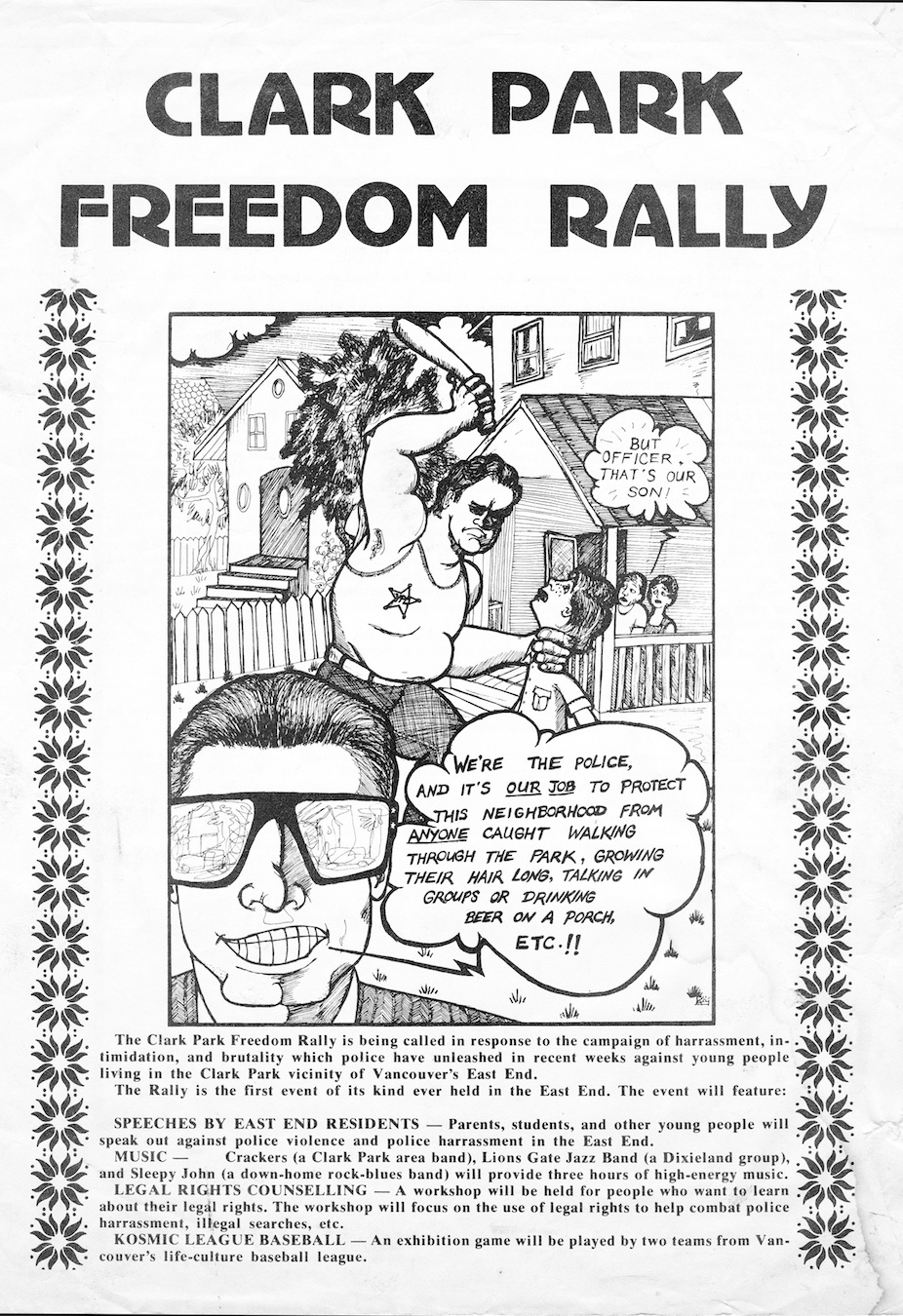

Another major focus of the tome is the Vancouver Police Department (VPD)’s just slightly under-the-radar H-Squad, who would go into the parks undercover to target the status-quo-threatening Clark Parkers. One gang member was picked up and thrown into the water in not-so-nearby Steveston Harbour. Perhaps starting more problems than it solved, this led to the Clark Parker stealing a car to get back home.

“This is before, of course, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada, where police are given a little more mandate and direction,” Chapman explains of the H-Squad. “These are the wild and woolly ‘70s, where you could get away with a lot more. [But] even back then, they would’ve been considered really colouring out of bound with what that gang task force.”

For The Last Gang in Town, Chapman reached out to a number of former gang members and retired police officials. Access to surviving Clark Parkers was fairly easy, with many having reformed, and the statute of limitations on other crimes having long passed. Getting the H-Squad on record proved a bit trickier. Chapman reveals: “I filed a Freedom of Information request with the VPD and they didn’t have anything on file. Whether it had all been destroyed or not, it’s hard to say, because some of the record-keeping in the 1970s was not very good. Unless you have a specific incident number, it’s hard to find.”

But from the existing police transcripts and photos, to the press coverage from the time, to the anecdotes offered present-day, The Last Gang in Town is a fascinating look at how gang life in the city has evolved. “These guys, they were sort of the dinosaurs before the comet hit,” Champman theorizes, suggesting that today’s gangs come from a more upper-middle-class background than the Clark Parkers, who scattered by the end of the ‘70s. “Within a couple of years, the stakes are raised. No longer are the gangs interested in some minor breaking-and-entering, or territorial squabbles. Now they’re interested solely in the traffic of drugs.”

Chapman continues: “I didn’t mean to make the Clark Park Gang guys any more noble or anything like that, but they were less motivated by the greed and avarice of money. They sort of stuck together, there was a bit more of a code: things they would do, some things they wouldn’t touch, or whatnot. It was a different time. They were the last of their kind in that sense.”

Read more history stories here.