Braving chilly and overcast weather on August 26, 1956, baseball fans flocked to Capilano Stadium—the picturesque ballpark now known as Nat Bailey Stadium—to watch the Vancouver Mounties, in the midst of a disastrous inaugural season in the Pacific Coast League (PCL), face the Portland Beavers. The doubleheader itself was mostly uneventful, apart from fisticuffs erupting between the starting pitchers. The event’s true significance came as the city’s first quasi-legal Sunday baseball game.

For decades, Vancouver sports promoters had been trying to land a team in the PCL, the most prestigious of the minor leagues. Baseball diehards pointed to the success of the recent British Empire Games, and that the newly-founded BC Lions were drawing 20,000 each match, as proof Canada’s third-largest metropolitan area was ready for big-time sport.

So, it was large news in the summer of 1955 when C.L. “Brick” Laws entered negotiations with city officials about relocating his Oakland Oaks to Vancouver. Despite being one of the league’s most successful teams on the field, the Oaks had a run-down stadium and attendance was in free-fall; Laws was looking for greener pastures for his money-losing club. Vancouver had Capilano Stadium, a four-year-old ballpark at 33rd Avenue and Ontario Street, sitting vacant since a lower-tier professional team had folded the previous fall.

Vancouver’s Sunday blue laws cast a shadow over the negotiations, though. Sunday was professional baseball’s most important day for drawing fans and generating revenue, but all commercial activities including sports, games, and performances with charged admission were prohibited in Canada by the Lord’s Day Act. And, in British Columbia, a series of antiquated English statutes on Sunday observance inherited as law in colonial days were also still technically on the books—and contained stricter prohibitions against even amateur sports.

Still, there was hope. The Lord’s Day Act required provincial attorneys-general to issue a fiat to empower local authorities to prosecute violators, and with a distinct regional culture in B.C., provincial authorities had often taken a lackadaisical attitude. As a result, Sundays in Vancouver were more relaxed than much of the rest of the country, with locals able to enjoy parks facilities such as renting boats, and being allowed to play golf or go bowling without interference.

Amid an atmosphere of changing attitudes towards Sunday leisure in mid-century Canada, the Oaks relocation prompted demands for the city to hold a plebiscite on Sunday baseball at the upcoming municipal election. City council initially balked at the idea, caving to pressure from prominent church leaders who jammed the chambers in opposition. The city’s sports enthusiasts, however, quickly organized themselves to gather 16,000 signatures at hockey and football games over the course of a single weekend, forcing council to change its mind.

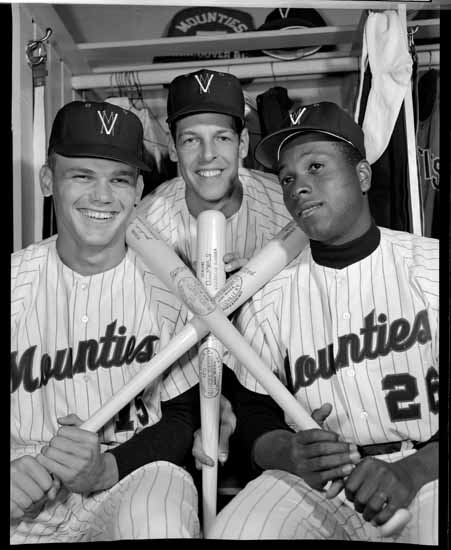

In what should have been a characteristically dull municipal election campaign, citizens were energized by the opportunity to express their opinions on the sports issue. The PCL club cleverly leveraged their own publicity efforts to surreptitiously help the “Yes” vote, announcing a new team name—the Mounties—and launching ticket sales just days before voters went to the polls. With a record turnout, Vancouver endorsed Sunday sports by a slim majority.

The problem was that, apart from knowing that enabling legislation was required at the provincial level before they could pass a bylaw, city council wan’t really sure what to do next. That winter they sent three vague requests for action to Victoria, appealing directly to Premier W.A.C. Bennett, who avoided being forced into a no-win decision by delaying and obfuscating for months. Then, with the legislative session winding down, he finally explained that city officials should have drafted specific legislation for consideration, but that it was too late for any action that year.

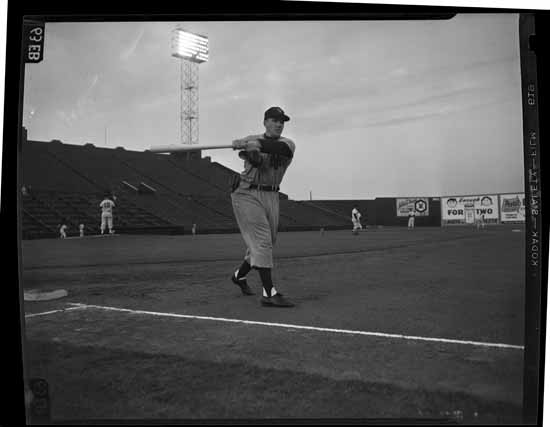

Resigned to making due without Sunday games, Mounties general manager Cedric Tallis was forced to hastily reschedule 13 doubleheaders. Within days of the home opener, a Mounties game was significantly delayed when the assigned umpires were nowhere to be found. Not knowing the new schedule, they hadn’t even arrived in town, leaving the Mounties to recruit two locals as last-minute substitutes. The incident was a harbinger of a disastrous season, as the Mounties struggled on the field and at the box office.

Before the season was through, city council grew frustrated with the provincial government’s unwillingness to even discuss the matter, and unilaterally enacted a legally dubious bylaw to allow Sunday baseball. Church leaders swiftly denounced the city’s action and launched a court challenge, but the Mounties managed to play the city’s first Sunday ball games that August (starting with the Portland Beavers match) and September before the B.C. Supreme quashed the bylaw as clearly exceeding council’s powers.

With the Mounties finishing last in the standings, Laws lost even more money than during his last year in Oakland, prompting him to sell the team that winter to a community-ownership group led by burger-and-fries magnate Nat Bailey. After Premier Bennett again refused to change the law that winter, the team was in a tough spot for the 1957 season. With 11 Sunday doubleheaders already booked and the team counting on that revenue for its financial survival, they had little choice but to break the law. In good faith deference to the provisions of the rejected legislation, club officials at least promised not to sell tickets on Sundays or play past a 6 p.m. curfew.

More than 5,600 spectators turned out to watch the Mounties and San Diego Padres play the season’s first Sunday games on the afternoon of May 5. Two uniformed policemen paid a visit to Capilano Stadium, inquiring whether the box office had sold any tickets that day and taking down the names of the club’s management, but they didn’t disrupt play. Officers were back the following Sunday.

Speculation was rampant about whether the Mounties would actually face prosecution. Eventually, club officials were served a summons that June to appear in police court, but the Mounties’ lawyer managed to secure one delay after another to enable the team to keep playing outlaw Sunday games all summer long.

Excelling under a new manager, Charlie Metro, the much-improved Mounties were keeping pace in a heated pennant race. Baseball fans from near and far raved about the delightful ballpark atmosphere and fan experience at Capilano Stadium. Organizers even found a way to turn the quirks of the Vancouver Sunday to the Mounties’ advantage on the field: as the 6 p.m. cutoff approached, the groundskeeper would run the big clock in centre field faster or slower, depending on whether the home team was clinging to a close lead or needed extra time for a few more at-bats to catch up.

When the Mounties’ case finally went to trial that October, the club was found guilty of contravening the Lord’s Day Act and fined $50 on each of three counts. Tallis and his assistant general manager were fined a total of $3 each.

Soon, news of similar charges against a billiards hall operator fuelled public perception that Sabbatarians emboldened by the magistrate’s ruling were pushing for tighter enforcement against other supposedly unwholesome Sunday activities. Like the Mounties before them, pool hall operators decried the discriminatory treatment. When their concerns went unheeded, they retaliated by filing formal complaints with local authorities against curling clubs, bowling alleys, symphony concerts, golf courses, paid activities in city parks, and every other illegal Sunday recreation they could find.

For months, people had been hinting at this as a possible strategy to highlight unfairness of tolerating some but not all infractions. But, once it was put in practice, everyone was shocked that the city prosecutor cooperated—announcing that, after having submitted evidence to the attorney-general, he was awaiting a fiat to come down on the city-owned pitch-and-putt in Stanley Park. Moreover, the police commission made the enforcement of “the Lord’s Day Act in every particular” official city policy.

The controversy led city council to hold another plebiscite on the issue, and the results were in favour of Sunday sports. Relenting in the face of this overwhelming majority, the Social Credit government passed the city’s charter amendment in the spring of 1958—on the condition that the legislation would be subject to court review before taking effect. While awaiting the ruling, the Mounties continued to play illegal Sunday games that season, and actually sold tickets at the ballpark those days. Despite stern admonitions from the authorities, no one bothered to file formal charges.

After the B.C. Court of Appeal confirmed the validity of the charter amendment, allowing city council to enact a corresponding bylaw, Vancouver’s first Sunday with fully-sanctioned commercial sports with admission charged—June 29—was a quiet affair. Apart from a scheduled doubleheader between the Mounties and the San Diego Padres, none of the city’s sports promoters rushed to organize events to take advantage of the new bylaw. In a last-ditch effort, the Lord’s Day Alliance took the fight to the Supreme Court of Canada, only for the court to confirm the right of provinces to legalize Sunday sports.

Sunday movies, concerts, and stage performances were legalized in Vancouver in 1963, and similar freedoms were extended across the province in 1969. Across Canada, Sunday restrictions were likewise slowly loosened over the ensuing decades, culminating in the Lord’s Day Act being struck down by the Supreme Court in 1985 as incompatible with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Mounties and their fight for Sunday baseball served as a crucial spark in securing the more liberal Sunday enjoyed today.

Read other stories from the Community.