A rebel at heart, Tom Dixon left art school by the wayside and somewhat haphazardly became a self-taught industrial designer. Following a motorcycle crash that left him with broken limbs and a bruised ego (he was distracted by a beautiful girl), the Brit took up welding to repair his bike. “As a direct consequence of knowing people superficially through the club business—they were all photographers and video makers and shopkeepers that wanted stuff—it was a very organic evolution into that becoming a business,” explains Dixon, who recently visited Inform Interiors on the last leg of his North American multidisciplinary lecture tour. “So I added a couple of guys to do the welding and I ended up with 17 people in a big warehouse in South London that were engaged in making stuff.”

You wouldn’t know it by his nonchalant demeanor, but Dixon has received his fair share of accolades over the years. His work has been acquired by top museums including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and his body of work to date has earned him an O.B.E. designation (that’s the Order of the British Empire, which recognizes distinguished service to the arts and sciences). His medal currently resides with his holiday decorations. “It’s where the cleaning lady put it. She didn’t know,” he chuckles. “Occasionally people get medals. But you can’t wear a medal on a daily basis, which is quite a shame.”

No matter, metals have surfaced in Dixon’s life through his work instead: his lighting, furniture, and accessory items lean toward a bare aesthetic and are industrial in nature. Insisting that his style is due to the fact that he had to be “rather dumb and basic at the start”, Dixon’s main influence has been the industrial process itself: how things are made and the machines that make them. “I think there is a space for something that is a bit less plush. There are a lot of slick companies doing pretty products and refined things. So, in a way, that gives us an advantage at the moment, a distinction in terms of our aesthetic, which I think is one of the most important things right now: a point of difference.”

The Dixon difference then, lies in approach, and the designer isn’t courting his own crowd. Given a choice of exhibits to visit, he’d choose sculpture over design. This wayward nature has influenced many of his now famous items, including his Beat lights, which got their start as a non-profit project in India. Likewise, his serving ware’s origins stem from past restaurant designs. “Having projects gives way to things like this because we can’t find them so we just make them. Something about diving into the kitchen and being a professional chef or running a restaurant influences me much more—and much more effectively—than how most product designers work. They have a client, the client briefs them, and they do what they’re told. I’ve never really been able to do that. I’m not a very good designer. I can’t do it on purpose.”

Dixon’s approach has caused what he refers to as a mutation into a bunch of different typologies. “I’m doing a collaboration with Adidas, so I’m a fashion designer,” he explains. “I’m doing scented candles, so I’m a perfumier. It’s not one thing, so you can’t get bored of design. It’s just an action that you give to something else.”

The Sea Containers House refurbishment has been a different kind of project for him. Working through his high-concept architectural offshoot, Design Research Studio, the 14-floor 1970s building on the bank of the River Thames in London is slated to re-open later this year, marking a near four-year project for Dixon. “I’ve never done something for so long. It’s been nice to do some 360 rooms and different categories like the spa. I like this idea that you’re supporting this whole world that you don’t know anything about.”

All these years later, the college dropout is now a savvy businessman, keen to learn about anything that will further cement him in history. And, ever the patriot, he’s even interested in teapots. “I feel it’s a good brand icon. I’m trying to work with the British-ness,” he says. “It’s true in a way that the things that fascinate me have a narrative and a heritage. I think most people are really interested in a sense of origin, and there’s no doubt that’s where I come from. In an increasingly globalized world I think it’s important to hold on to that.”

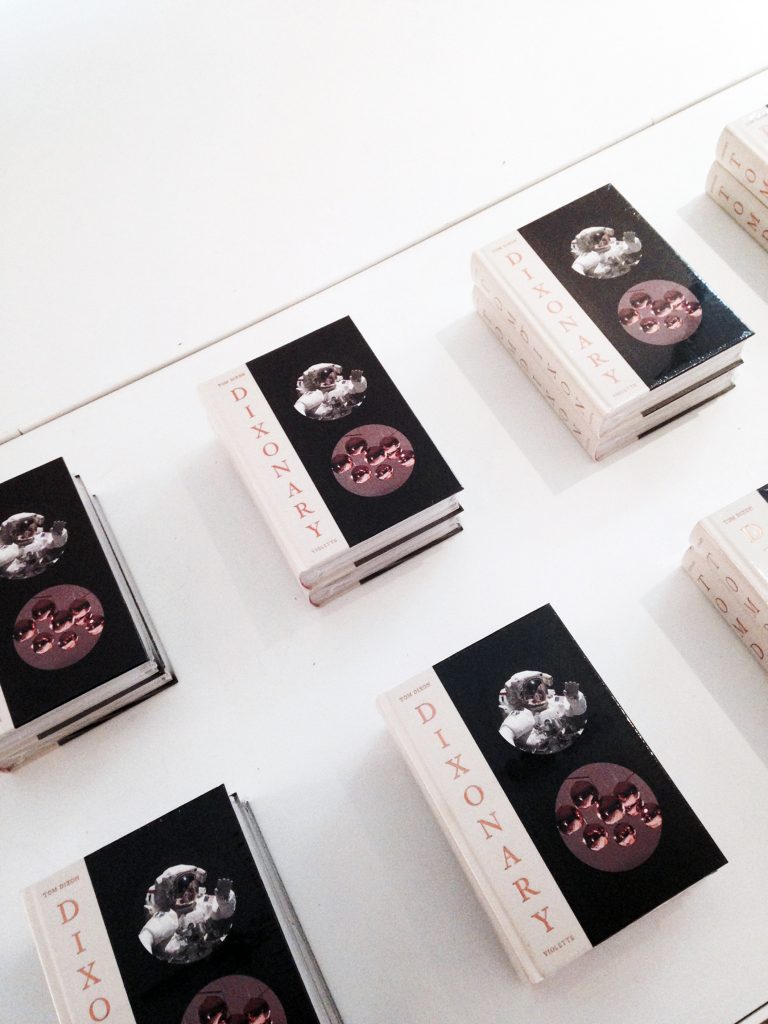

Inform Interiors photos: Kimberly Budziak