There is something very compelling about an artist’s studio; a den of creativity, it can take many forms. Some studios come in the shape of small, dark, shared spaces. Others are elaborate 10,000-square-foot warehouses. Andy Warhol dubbed his “the Factory”, a place of production that churned out pop art and a revolving-door hangout that glamorized the idea of the studio.

For Vancouver’s Damian Moppett—who, come November, will be the first Canadian to have his art shown at the Rennie Collection at Wing Sang—the studio often becomes the very subject of his work. His space is cluttered with works in progress, boxes, crates, sculptures, paintings and a scattering of furniture, but amid it all, wearing a cream-coloured shirt, off-white denim and a pair of Chuck Taylors, Moppett has an air about him that is smooth and confident, befitting of his 20-plus years in the Vancouver art scene.

A Vancouver resident since 1990, Moppett has also secured a position for himself among the tight-knit world of elite collectors. He is represented locally by Catriona Jeffries, and until earlier this year was represented internationally by Yvon Lambert (of Paris and New York). He is now considering other options in the U.S. and U.K. and to date his artworks have been exhibited in both of those countries, as well as across Canada, in Germany, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands. For his solo exhibition at Wing Sang, Moppett will show one new work, a sculpture commissioned by the gallery, to round out the remainder of the exhibition, which consists of artworks from the Rennie collection dating back to 1998.

Throughout the years, Moppett has largely based his work on the idea of how art progresses in the studio. His practice—which spans the mediums of photography, painting, sculpture and film—is focused not so much upon the completed work as on the process that goes into his achieving the end result. Bruce Nauman played with a similar idea in his piece Mapping the Studio I and II, a video compilation taken from 42 hours of tape recorded in his studio at night with an infrared video camera. When watching the footage, the viewer is confronted with the question: can the studio, in and of itself, be considered a work of art?

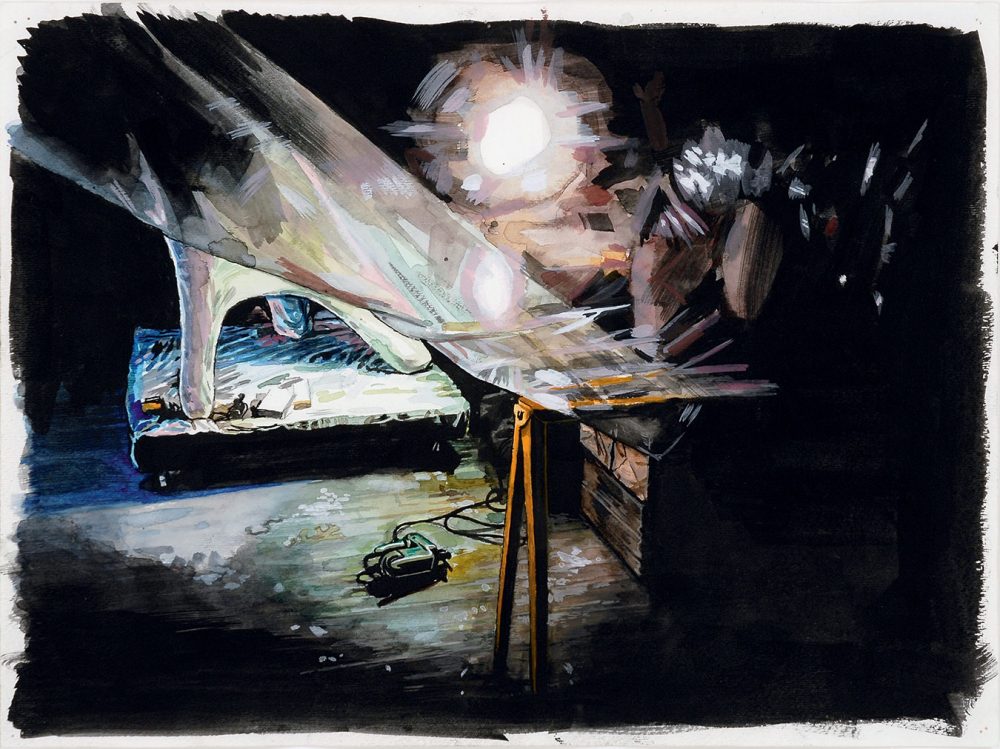

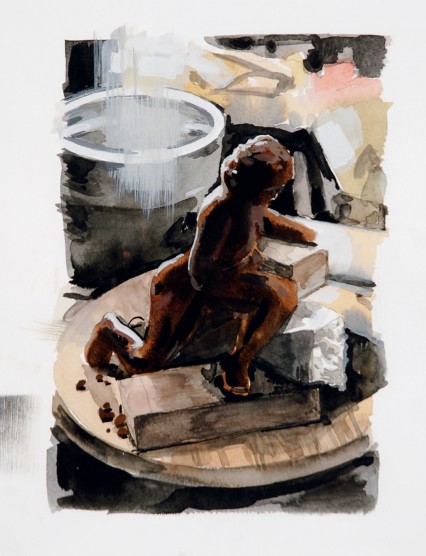

“For me, it’s a form of self-portraiture,” says Moppett. “I think it started because, in my sculpture, I always want to come back and rework things to get what I’m looking for. In a way, I want to show the stages of a sculpture’s evolution because [those stages] may not be visible once finished. Works look different and have a completely different life when in the studio, compared to how they exist in a gallery.” Pieces such as Figure Study in Clay and Studio Under Plastic capture the studio experience beautifully for the outsider, who can not only see the raw edges of unfinished work, but also pick up on the character of the artist’s studio, where paint cans and brushes move beyond their banal existence. “In the studio, [the works in progress] blend in with everything else. Everything gets levelled in regards to importance,” Moppett says. “The studio is a personal and private space while also being romantic and highly photogenic.”

Moppett’s interests are reminiscent of the late sculptor Constantin Brancusi, an artist who, along with other sculptors like Auguste Rodin, Medardo Rosso, and Anthony Caro, has informed Moppett’s work as he explores the relationship between sculpture, studio and abstraction. Yet one might wonder why he sculpts at all when painting comes so naturally to him. “I was never interested in just being a painter or just being a sculptor,” Moppett explains. “Painting isn’t always the right thing for some ideas.”

His ability to move between mediums is nowhere more evident than in 1815/1962, a short film in which Moppett plays a trapper in the woods who constructs a rendition of Anthony Caro’s Early One Morning out of forest scraps. So named for the year in which the trapper is supposed to be living and for the year Caro made Early One Morning, the piece has had a profound effect on Moppett’s subsequent work. “It’s a mother to most of the sculpture that I’ve done since,” says the artist. Here, art lives outside of the studio—a rarity in Moppett’s oeuvre—and becomes more function than form. “I like the idea of taking this esoteric, modernist, sometimes elitist sculptural form and turning it into something that would kill a small animal.”

It makes you wonder if art itself falls prey to its own trappings once it is released out into the world. Free from the safe confines of the studio, it is subject to something else entirely.

Photos: Site photography, courtesy Rennie Collection.