Manolo Blahnik spends most of the year travelling, but he’d rather be at his home in Bath watching old films. Without his thousands of DVDs and Blu-rays on hand, he turns to the Turner Classic Movies channel in whatever hotel he finds himself in. Just this morning, he watched Mildred Pierce. “Joan Crawford is perfection,” he says with a slight Spanish accent that has been affected by his decades spent living in England. “I haven’t been to my home in the last two years,” the legendary shoe designer continues. “Maybe, in the last year, two weeks in total.”

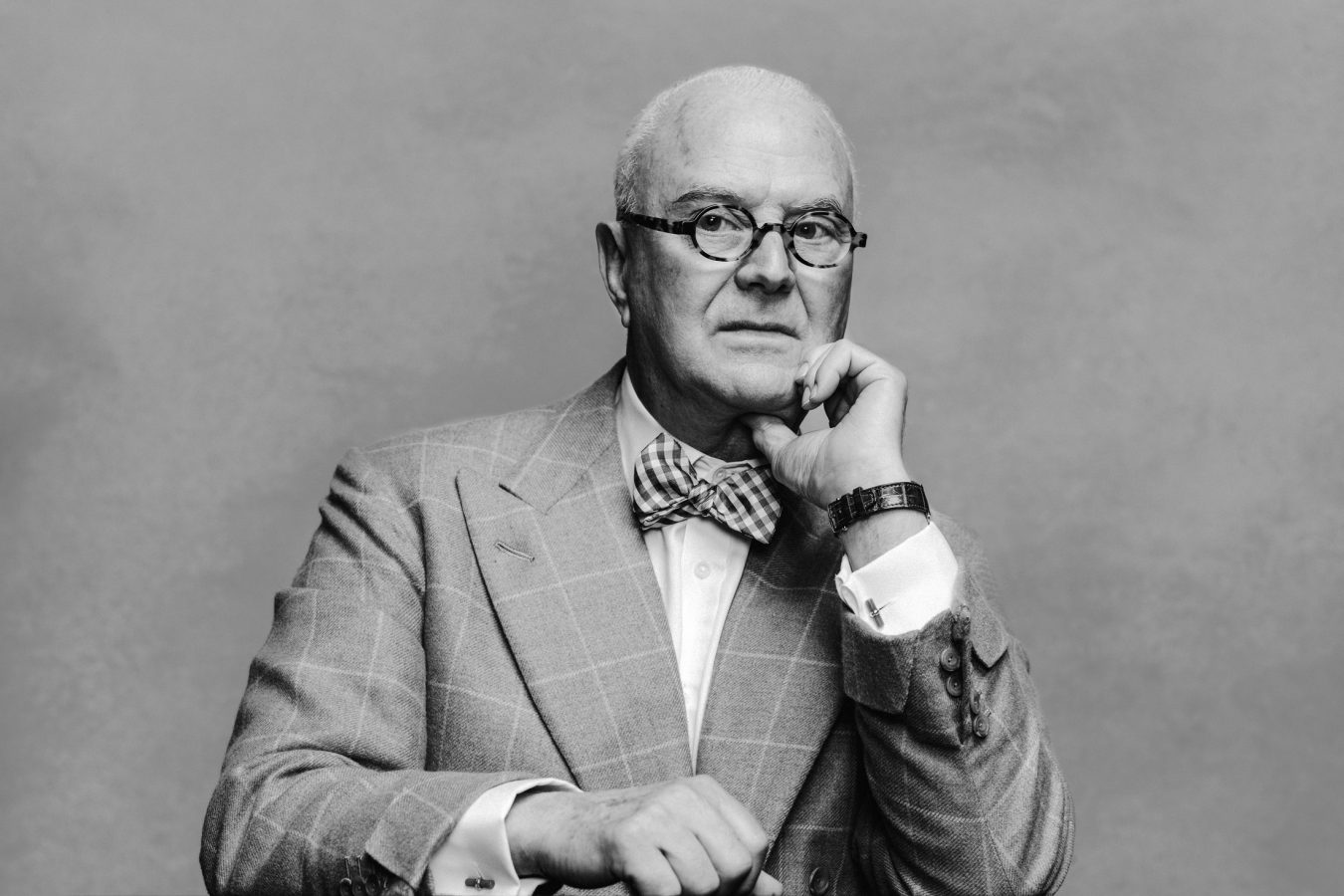

This week, he is in Toronto for the opening of “Manolo Blahnik: The Art of Shoes” at the Bata Shoe Museum (on now until Jan. 9, 2019), the fifth and last stop of his celebrated career’s retrospective that started in Milan in 2017. Though he is 75, retirement is not in Blahnik’s periphery—“unless I drop dead tomorrow.” But that is impossible to imagine given his childlike energy. Despite almost five decades in the hectic luxury footwear industry, he has never lost his sense of romance towards fashion and glamour.

Blahnik grew up on the isolated Canary Islands, far away from the glitz of high-street style. He thinks his birthplace has now lost its charm due to tourism, but things were very different when he was a child. “Magical, really,” he reminiscences. (Unfortunately, the majority of his family mementos were eventually lost in a London flood and a robbery in Bath. “Most of my youth is gone,” he says; the documentary filmmakers of Manolo: The Boy Who Made Shoes for Lizards had to reconstruct scenes from his childhood to tell that part of his story.)

Despite the Canary Islands’ distance from popular culture, it was in this remote place where Blahnik fell in love with fashion, patiently waiting for the latest Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar to arrive via boat from Argentina. Young Blahnik, with his mother and sister, would pore over the glossy pages and dream of faraway places. “I was the one who loved things, the pictures, my God, how wonderful the pictures,” he remembers. “And that was the beginning of my interest in what people wore.” His nanny’s Catalan espadrilles made a lasting impact, particularly the way the black laces tied around her ankles. “I loved it,” Blahnik says. “It was such a beautiful thing.”

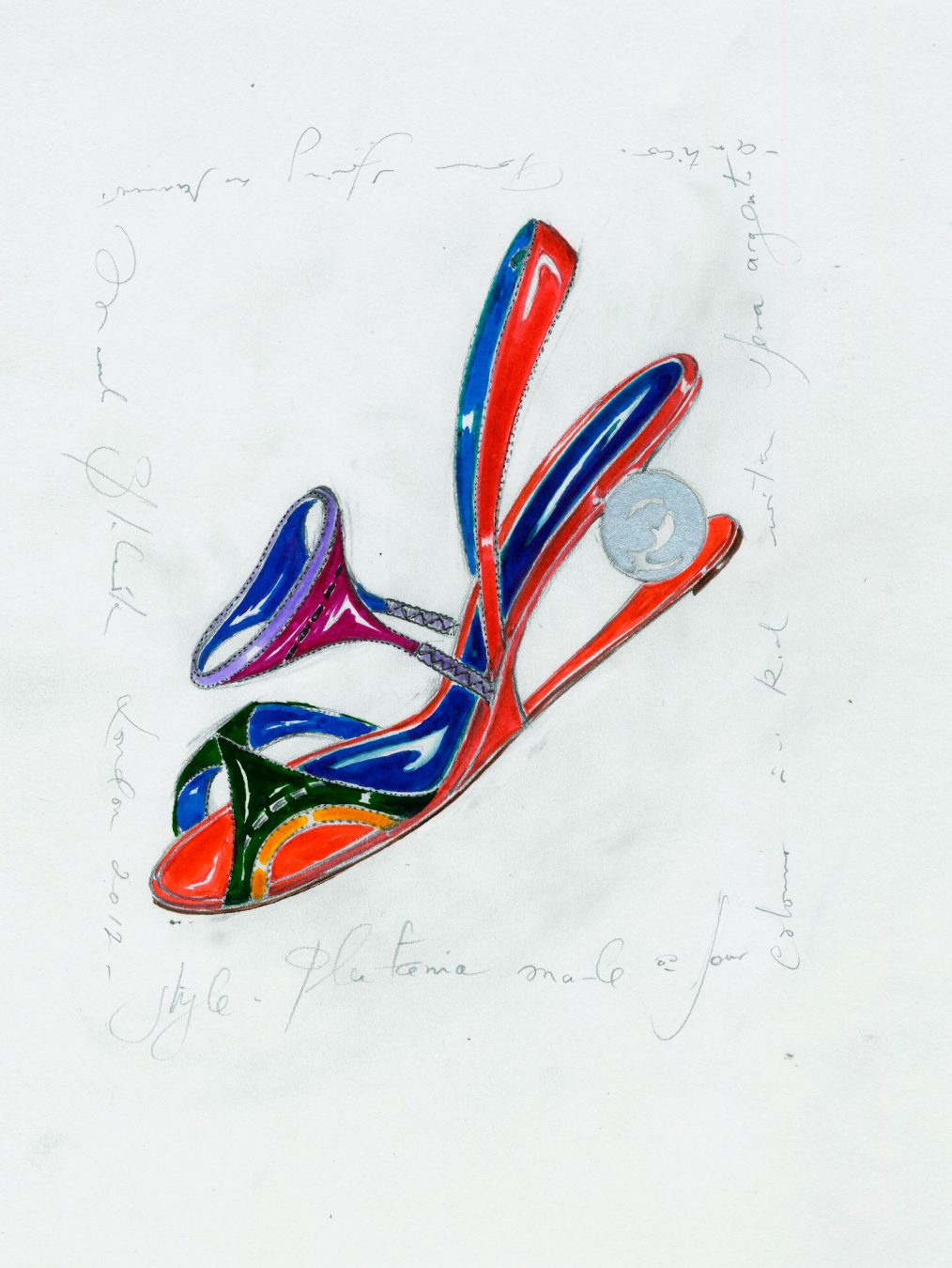

He was always a dreamer, never paying much attention in school, always doodling instead of taking notes. His mind wandered in many directions, from Hollywood stars to Alexander the Great. “I loved Linda Darnell and other people and things that nobody knows anymore,” says Blahnik. “And all my life I was doing research on the campaigns of Alexander the Great. Isn’t it crazy? It’s obsessive, actually.” These childhood fixations eventually materialized in his footwear designs. Take, for example, the best-selling pointy BB pump inspired by Brigitte Bardot, or the designer’s Trellis gladiator sandal, a pink suede wonder adorned with matching roses: it’s at once ready for an ancient battle and a contemporary garden party. “This is real,” Blahnik says. “I say, ‘Oh, do extremities, my dear, because this is fun.’”

He was always a dreamer, never paying much attention in school, always doodling instead of taking notes.

When he left the Canary Islands, it was to attend the University of Geneva, first studying international law and politics and later changing his majors to literature and architecture, after which he moved to Paris to continue his studies. In 1968, he relocated to London, where he worked as a buyer at a fashion boutique. On the side, he drew shoes, accumulating a portfolio so striking as to impress Diana Vreeland, then the editor-in-chief of American Vogue, who convinced him to start his own business.

“She was wonderful to me,” remembers Blahnik, who still refers to her as Mrs. Vreeland. “She told me a million times, ‘What you do is different from everybody else. It’s total fantasy, a cross between a dream and the reality, but you have to think about something always: don’t do boring shoes. Do masterpieces.’”

The shoes in his first collection, presented at the Ossie Clark fashion show in 1971, were so uncomfortable that the models could barely walk. But he learned proper construction quickly, and a year later, he established Manolo Blahnik Int. Ltd. with the opening of his first boutique in Chelsea, London, which remains the company’s flagship store today.

Vreeland’s advice aside, the truth is that Blahnik couldn’t be boring even if he tried. It’s what attracts the likes of Rihanna and avant-garde label du jour Vetements to reach out for collaborations. “I never talked to Rihanna to do the shoes. She bloody came to us,” he says. “And Vetements, they came to us and said, ‘Yes, we love you.’ They’re fun.”

The Vetements boots are an achievement in gravity—waist-high chaps-like stunners that could be considered a departure from Blahnik’s often-dainty creations. In 2006, he designed shoes for the ultimate queen in Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. He really can do it all. “Everything in my life just happened,” he says, shrugging off his success as though it is not a product of his own talent and hard work.

In a time when luxury conglomerates have acquired most of the designer brands, Manolo Blahnik Int. Ltd. remains privately owned and family run. Blahnik is the creative director and chairman, and his niece Kristina Blahnik took over as CEO from his sister Evangelina in 2013. To this day, the designer insists on working hands-on with every prototype at the company’s Milan factory.

“I like to do everything myself, but I don’t have much time,” he admits. “Last year I wasn’t [there] because I was so exhausted thinking about the Milan exhibition.” Now that “The Art of Shoes” is wrapping up its tour, he is determined to spend more time in the factory. His absence, he says, most likely delighted his staff. “But now, starting from the next season,” he says jokingly, “I’m going to be really, really impossible again.”

Blahnik insists he is not a perfectionist, but that is difficult to believe. The 200-some shoes in his retrospective exhibition come from his immaculate archive; he has kept size 37 samples of every design he ever dreamed up, creating a library of 30,000 shoes and corresponding sketches.

Then there is his impeccable appearance, which has landed him on Vanity Fair’s International Best Dressed Hall of Fame list. When it comes to his own style, the designer prefers double-breasted suits from Anderson & Sheppard on Savile Row in London. Suits are his daily uniform, a dressing tradition he’s retained despite the changing trends. He admits that he once, inspired by James Dean, owned a single pair of blue jeans in the 1960s. “But then why are we still doing jeans now?” he asks disapprovingly.

Blahnik longs for the days of Old Hollywood glamour. “I don’t see beauty as I used to,” he says. “And I love beauty. That’s why I go to a museum. In museums, I get lost because I see beauty.” With “The Art of Shoes,” we can do the same.

Stay in fashion.