It was a wet winter’s afternoon and I shifted uncomfortably on the blanket beneath me. The artist paused and then brusquely flipped a page, saying, “I’ll start a new one.” Oops. It was difficult to remain motionless on the scratchy blanket, which was impressing a woven pattern onto my backside; besides, it was damp and cold in the artist’s studio, located in her paint-cluttered attic where the “light was the best” but the comfort level not quite so.

I liked her paintings, which sold at a gallery where I was then working. Thinking it would be a nice (if narcissistic) gift for a love interest at the time, I approached her about commissioning some drawings of me in my, um, natural state. We had a loose agreement that I would sit for her a few times and if I liked any of the results, I could purchase them directly. In retrospect, it was fortunate there was no binding contract, as I left with empty hands and, thankfully, the love interest with no potential blackmail material. The artist ended up selling them to the gallery instead, and today, several art patrons in the Greater Toronto Area are now unwitting owners of overtly “Rubenesque” versions of me.

The commissioning of artwork is pervasive throughout history; portraiture finds its recordable beginnings with Chinese court paintings dated even earlier than the well-known Faiyum portraits, circa 1st century BC. Works were typically commissioned by the monarchy, the wealthy, and the religious, with the desire to honour personages, represent religious or allegorical themes for didactic or decorative purpose, and to pay homage to historical events. Noteworthy examples include Sandro Botticelli’s allegorical The Birth of Venus, commissioned by the wealthy 15th-century Medici family to decorate their manse; and, Leonardo da Vinci’s inimitable 16th-century portrait of Lisa del Giocondo—a.k.a. the Mona Lisa—the wife of a wealthy silk merchant, commissioned in celebration of the birth of a son. In more modern times, works such as Marc Chagall’s stained glass windows at the Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem and Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Who is Living—think floating shark in a tank of formaldehyde—commissioned by advertising giant Charles Saatchi in 1991.

In establishing some guidelines for the commissioning of a work, it is prudent to incorporate lessons learned from history. First, be sure you are familiar with the style in which the artist works. While not a commissioned work, one can only assume Queen Elizabeth II knew what was in store when she allowed Lucian Freud to paint her portrait in 2001. Although he is considered by many to be the most brilliant contemporary portrait painter, Freud’s oil on canvas was panned by critics as it shows an aged, pinched Queen Elizabeth awash in shadows and lines. True to his uncompromising style, it nevertheless resides in The Royal Collection. So, by knowing the style in which your artist works, and in asking for recommendations from past clientele, you are practising due diligence.

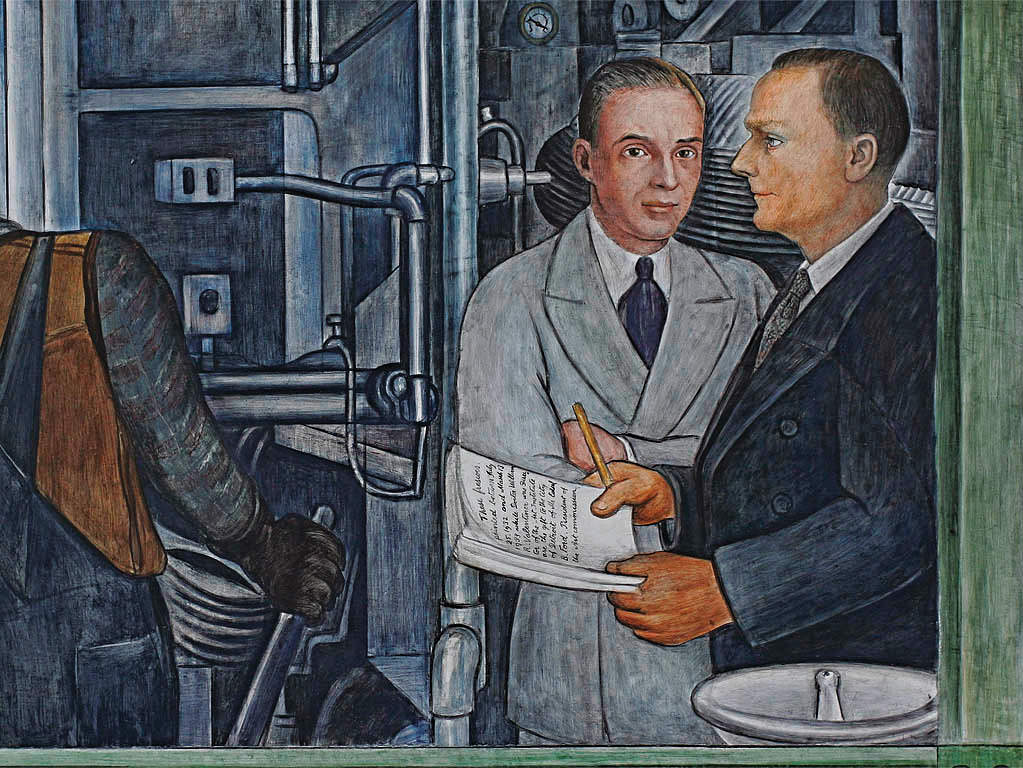

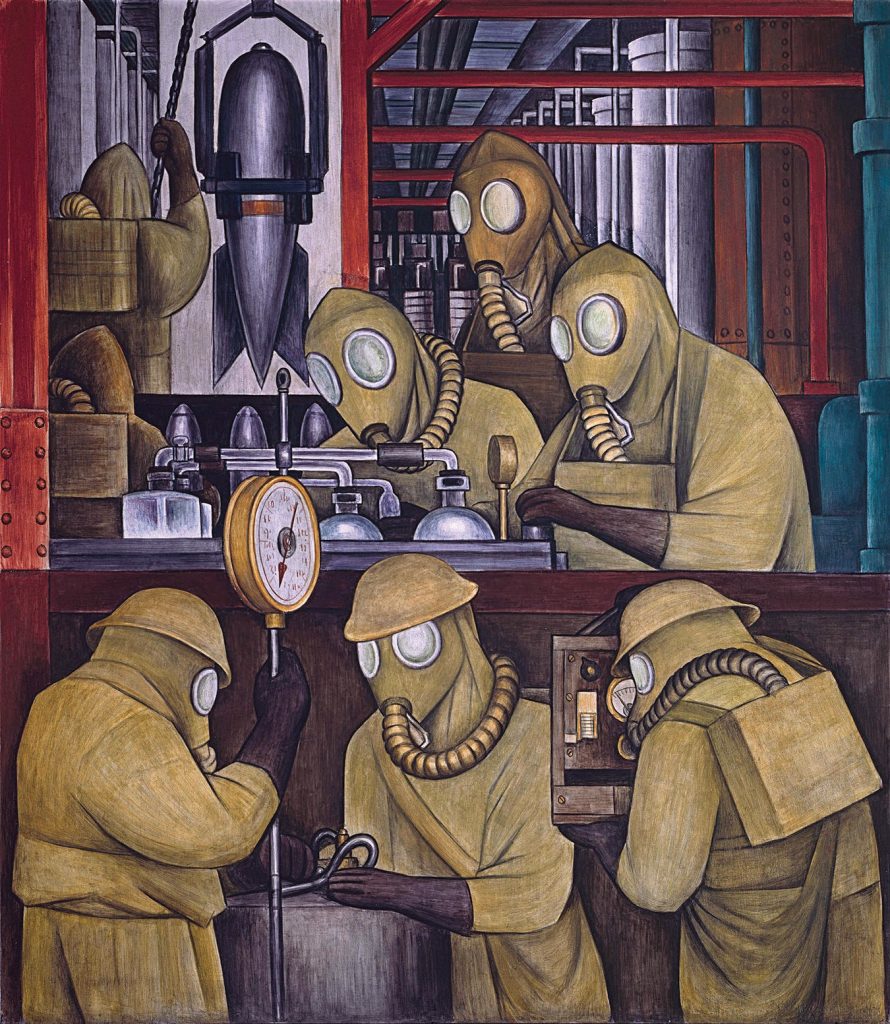

If you are not comfortable placing faith in the artist and bequeathing total creative license, it pays to be clear about your expectations of the final product. Imagine the surprise of Ford Motor Company’s president, Edsel Ford, when in 1933, he beheld the mural commissioned from renowned (Marxist) artist Diego Rivera, only to see a 27-panel critique of mass production and its underlying commentary on man’s subjugation to machine, entitled Detroit Industry. It is worth having a detailed conversation with the artist about the desired product; it is also common practice to see preliminary sketches before the work is created in its finality.

A contract signed by you and the artist with an articulated payment schedule, completion date, insurance coverage, and delivery and installation instructions creates transparency in the process and an understanding of responsibilities for both parties. Consider the 1898 case of James McNeill Whistler, who was commissioned by Lord Eden to paint a portrait of his wife. Upon completion, Eden disputed the initially agreed-upon price. Whistler responded by painting out Lady Eden’s head and replacing it with another. Eden sued him demanding he complete the portrait; instead, the courts ruled Whistler need not complete the portrait but must pay Eden for damages. It warrants having a clear contract.

I occasionally wonder what would have happened if I had objected to the selling of my dimpled doppelganger. Would the artist have maintained copyright and therefore control of the image, despite the fact that I was the subject? Nevertheless, it is best practice for the commissioner to be aware of copyright issues and what this means for reproducing an image of your painting, sculpture, drawing or otherwise.

Since my initial brush with that commission, I have only recently revisited the concept. This time, however, I’m going with a landscape—an ethereal oil on canvas. Less daring perhaps, but a whole lot warmer.

Photos: Detroit Institute of Arts.