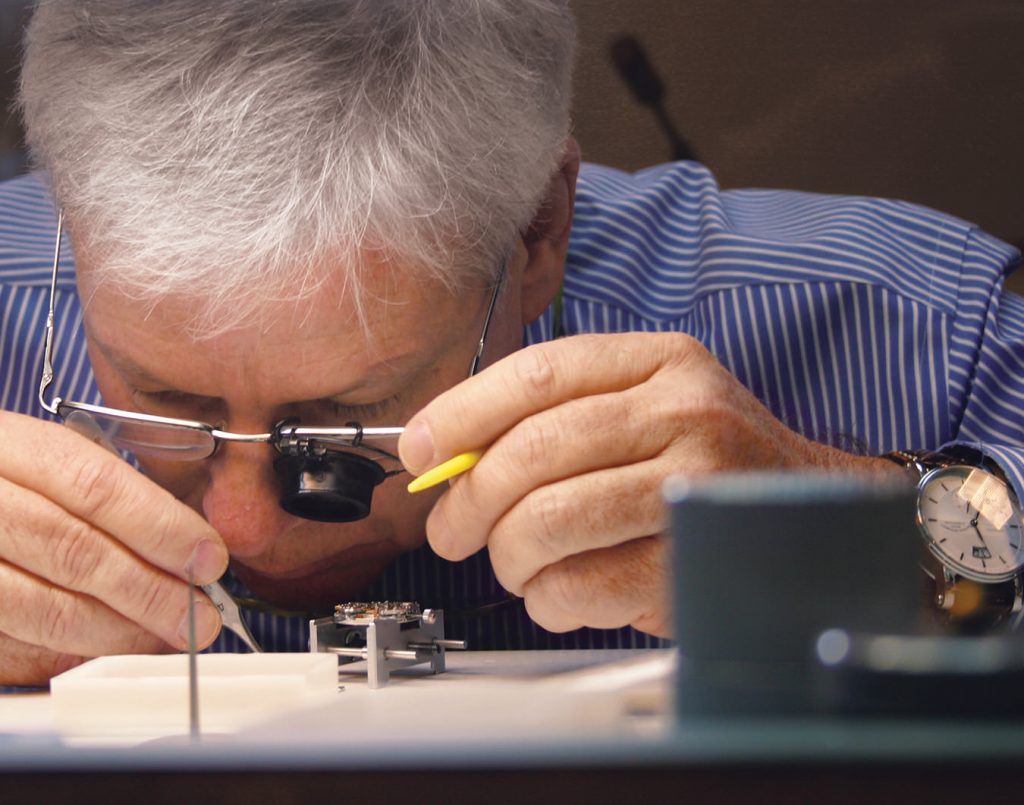

To be a great watchmaker, one must possess two qualities: patience and precision. Jean-Jacques Maurer is characterized by these two traits, not only in the mastery of his craft, but also in his demeanour. He demonstrates his patience, as he answers my every question, and his precision, as he explains every intricacy.

Growing up in Biel/Bienne, Switzerland, Maurer spent countless hours sitting at his grandfather’s side, watching him practise the trade. His first impression of watchmaking stuck with him for a lifetime, despite a few smacks he received to the hand when caught tinkering with his grandfather’s tools. Now, after 50 years as a watchmaker himself, Maurer understands his grandfather’s reaction. “A watchmaker’s tools last a lifetime, and longer,” he says. “I inherited my grandfather’s at first, but now the technology has changed. Over time, I have acquired my own tools, and they are very personal and precious to me. They have become somewhat of an extension to who I am, and what I do.”

Maurer began his first apprenticeship as a watchmaker with Omega at age 16. He worked there for six years before being sent to Montreal to represent the company at Expo 67. His curiosity brought him further west. He and his wife eventually deciding to settle in Vancouver, where he opened his own business, Time and Gold, a retailer specializing in the sales and repair of fine mechanical watches. It was 1975, a time when watches were undergoing radical technological changes, with the introduction of quartz. Many people predicted this would be the end of mechanical watches, which had been alive and ticking since the 16th century. “It was a turning point,” Maurer reflects. “And a very scary moment to be a watchmaker. The future was uncertain.”

To Maurer, it was also a bit sad. “Quartz watches were too perfect, too clinical,” he says. “There is a certain magic about the fine mechanism of a watch that makes it alive. I think there is a something between time and one’s personal life that makes no other item as sentimental as a watch. I often see them passed down from generation to generation. With care and maintenance, a watch will live through the generations.”

He probably wasn’t the only one who felt this way, as quartz watches have now begun to disappear. “Today, there is a great demand for watchmakers,” says Maurer, “but it is certainly not a career for everyone. It is a very technical and meticulous trade.” When a watch is brought in for service, which is required approximately every five years, it must be dismantled completely, no matter what the problem. Each and every tiny part is scrutinized, cleaned and lubricated before reassembly. “You must have patience, good vision and a very steady hand,” he insists.

“There is a wide array of watches available, and some makes have never strayed from mechanical. Every watch is unique and each presents its own challenges.” Maurer pauses, then says, “I suppose that is both the joy and frustration of being a watchmaker.”