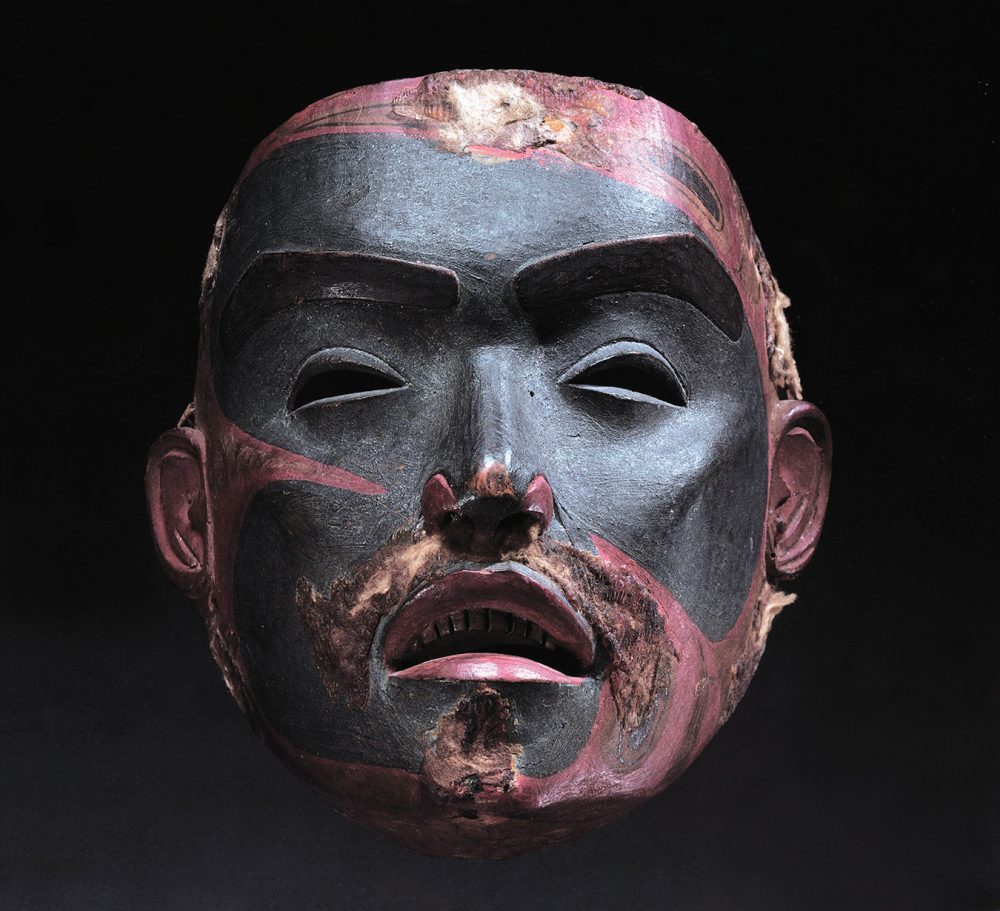

On October 5, 2006, over two dozen significant pieces of Canadian heritage began their journey home after 143 years abroad. Now residing in public and private collections in Canada, the objects were offered at Sotheby’s New York as the Dundas Collection of Northwest Coast American Indian Art—one of the most important private collections of First Nations objects to come to the market in decades. The collection, which left no lot unsold, featured on its catalogue cover a 19th-century polychrome wooden portrait mask made by the Tsimshian people of Metlakatla, or present-day Prince Rupert, British Columbia. It sold for $1,808,000 (U.S.) with buyer’s premium, a record for a Native American or First Nations object at auction. The Dundas Collection, which included a variety of Tsimshian and other First Nations objects, achieved over $7-million (U.S.) altogether, far exceeding their presale high-end estimate of $3.4-million (U.S.).

Crafted for ceremonial purposes, the objects were acquired by Reverend Robert J. Dundas of Scotland in 1863. Dundas’s diaries relay considerable detail about the communities from which these items originated and how they were collected. The diaries and artifacts together comprise a valuable historical record of First Nations artistic practices and culture. Many of the items were given up by the tribe as required upon their conversion to Christianity, and several belonged to Tsimshian Grand Chief Paul Legaic himself.

Collecting of this nature was not uncommon during the 1800s; with a substantial shift of societal values, today’s collectors would have considerably more difficulty in exporting such items of historic and cultural merit. Today’s collectors and purveyors of cultural heritage have Canada’s Cultural Property Export and Import Act to contend with. Coming into force in 1977, the Act works to ensure that the export of historically significant Canadian items is regulated; to designate institutions that are eligible to apply for grants to acquire cultural property; and to prevent the illicit traffic of cultural property internationally.

But what does “cultural property” really mean? The term is defined by UNESCO and refers to property that “on religious or secular ground, is of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science.” It encapsulates many types of objects ranging from scientific instruments to military objects to works of art and archival matter. The Canadian Cultural Property Export Control List, enabled under the Act, identifies eight categories of property, but generally speaking, items of cultural property are added to the Control List if they are older than 50 years and made by a person who is no longer living.

A set of medals, including the Victoria Cross that was awarded to Lieutenant Colonel Robert Shankland for his service in the First World War, was offered at Bonhams Auctioneers in Toronto in 2009. The sale received much publicity and generated concern as speculations arose that they could be acquired by an overseas resident wishing to send them outside of Canada. Nevertheless, under the Act, that person would be required to apply for an export permit, and federal laws allow for a delay of up to six months in issuing the permit, should there be a chance that a Canadian institution or authority wishes to make an offer to override the purchase. Federal grants are also available to assist designated institutions in purchasing the item. Although a public campaign in Winnipeg was launched to shore up funds for such a situation, it was unnecessary in this case, as the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa stepped forward and successfully bid $240,000 for the set.

Additionally, the Act prohibits the import of cultural property that has been illegally exported from a country with which Canada has a cultural property agreement on illicit traffic. Collectors seeking to import say, a Chinese ivory sculpture, or to export an Inuit parka with fur and feather trim, should also be aware that items containing parts made of endangered animals or plants are tightly restricted under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, administered under Environment Canada.

Regardless of how important artifacts leave our country in the first place, their repatriation to Canada is a significant re-addition to our cultural heritage. With much gratitude to the Canadian museums and philanthropists who purchased them, we and those who will follow us can now study, respect and admire the artistic and historical achievements of those who have shaped our national culture.

Photo: © 2011 Art Gallery of Ontario.