Fred Hollingsworth is at home. Literally—he is sitting in the large conservatory at the back of his North Vancouver house, listening to the water gurgle and drip across the basalt stones of an indoor fountain. In a figurative sense, too, he is here, existing wholly in the space he designed and built over 50 years ago, the place in which he practised a craft, raised a family, lived a life.

“I always thought that a house was the most important building I could draw,” the master architect says with the conviction of a man much younger than his 94 years. “I always used to try to build an environment that, if children were brought up in it, they felt that they wanted to be there, rather than go out and get into some trouble someplace.”

This simple idea—that architecture serves the family, strengthening the bonds between parent and child, enriching their lives—informs every line Hollingsworth ever drew. Over the course of his six-decade long career, he has built dozens of similarly styled homes, many of them on the North Shore. Along the way, he made a name for himself with a distinctly personal approach to residential design, winning awards and accolades not only from his Canadian colleagues, but from architects around the world.

“If you build a place [the family] wants to be in, rather than a four-square box and some windows, there’s a complete difference,” he muses. “I’ve found the kids who have been brought up in some of my homes have all done wonderful things. I joke about it with some of the people that are still in them, and they say, the house influenced these people, because it was designed [for them], so it worked for them.”

Today, we recognize Hollingsworth’s works for what they are: masterpieces of West Coast Modernism. A contemporary of American master Frank Lloyd Wright (who offered him a job back in 1951), Hollingsworth’s houses generally have shallow-pitched roofs with long horizontal planes and large windows. Natural materials (cedar, concrete) are a hallmark of his style. Most of his designs display a reverence for open space, and for the interplay between structure and site. Such is the power of Hollingsworth’s ideas that they seem completely natural, almost common-sense today.

Funny to think it almost never happened. “Architecture, for me—I actually stumbled into it,” Hollingsworth reminisces with a smile. During the Second World War, he worked at Boeing’s Vancouver plant, converting complex technical drawings for aircraft assembly into perspectives that could be read more easily by inexperienced workers. After the war, he played tenor saxophone and sang in the jazz band he formed, the Fred Hollingsworth Orchestra, which performed at dance clubs around the city. It was around this time he also met the woman who would become his wife, Phyllis.

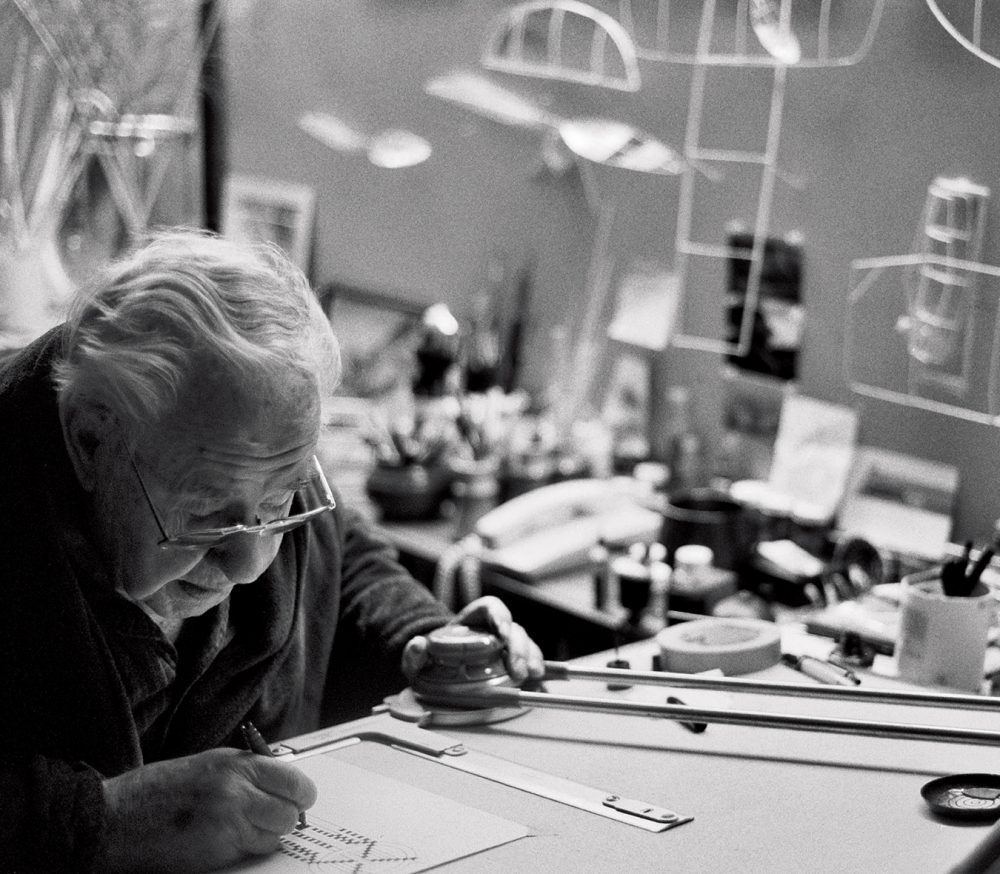

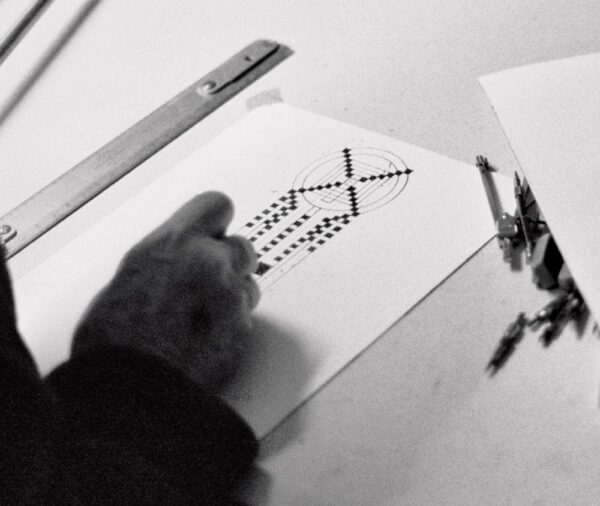

A superlative draftsman, Hollingsworth decided to try designing their future home. “I drew this house,” he says, raising his hands and gazing with pride at the walls and beams. He took his spec design to one of the leading architectural firms in the city, Thompson, Berwick and Pratt, the group responsible for the master design of the University of British Columbia campus. Needless to say, the partners were impressed, and soon gave him a job. The rest, as they say, is history.

“I loved it. I must admit, I loved it,” he says. “I thought I was trying to help people get a better life, and a better house. And I think I did that.” A smile crosses the architect’s face. It becomes clear that Fred Hollingsworth is not only home, he is at peace—with his work, with his legacy and with life itself.