I first experienced Kengo Kuma’s work in person in 2008, when biking through Japan with my son Makalu. As an architect who values traditional Japanese wood joinery and craftsmanship in the context of modern design and innovation, I find the renowned Japanese architect’s work both inspirational and influential to my own ideas and practices. While I often travel to visit contemporary architecture, far too often I am disappointed by the results. Seeing a building in an online photo spread tells you little about reality, and worse, begins to fog your expectations of a real experience with the context, space, materials, light, and spirit of the place. Time and time again, our experience with new architecture is manipulated by fantastic renderings and carefully employed camera compositions. Surface has replaced meaning, and architecture is reduced to a singular sensory question: how does it look? To pilgrimage, and experience in all the senses, is what enduring and culturally-significant architecture deserves. In Japan, Kuma did not let me down.

The trip took Makalu and I to many of Kuma’s projects, but it was the especially arduous journey biking to the mountain town of Ginzan that changed my perspective on what constitutes great modern works of architecture. It restored my love of modest restrained design, which serves all of our senses, including those we can articulate and those we can only feel. Ginzan is a little town with a small river where the main street should be. Wooden buildings line the water, with bridges connecting the sides; hot springs cascade through wood and stone troughs that descend from sidewalks, with seating areas to stop and dip your feet. There, Kuma renovated an historic inn to build the eight-room Ginzan Onsen Fujiya. Kuma’s design for the Fujiya respected the mountain town’s heritage by stitching together a masterpiece of old and new, using only natural materials, craftsmanship, and thoughtful detail.

The inn has five separate natural hot spring baths for the guests. Each bath is its own unique space, each with its own sensory and material expression. Makalu and I celebrated his eighth birthday there as the only guests in the Fujiya. It was quiet, and we spent hours visiting the baths together, exploring the spaces, running our fingers along delicate walls, playing with natural light filtered through layers of Japanese paper and bamboo. We marveled at how the stairs floated from the structure above.

Kuma’s architecture, like all great architecture, can inform our emotions; it can calm, it can quiet, it can help us reflect, it can draw us together, and it can create joy.

Cross-legged in our room, we ate course after course of vegetables. We laughed as father and son, and lay on our futon staring at a ceiling. We talked into the night about the mountains and forest around us, and the sounds, smells, softness, and air that seemed to bring the building alive.

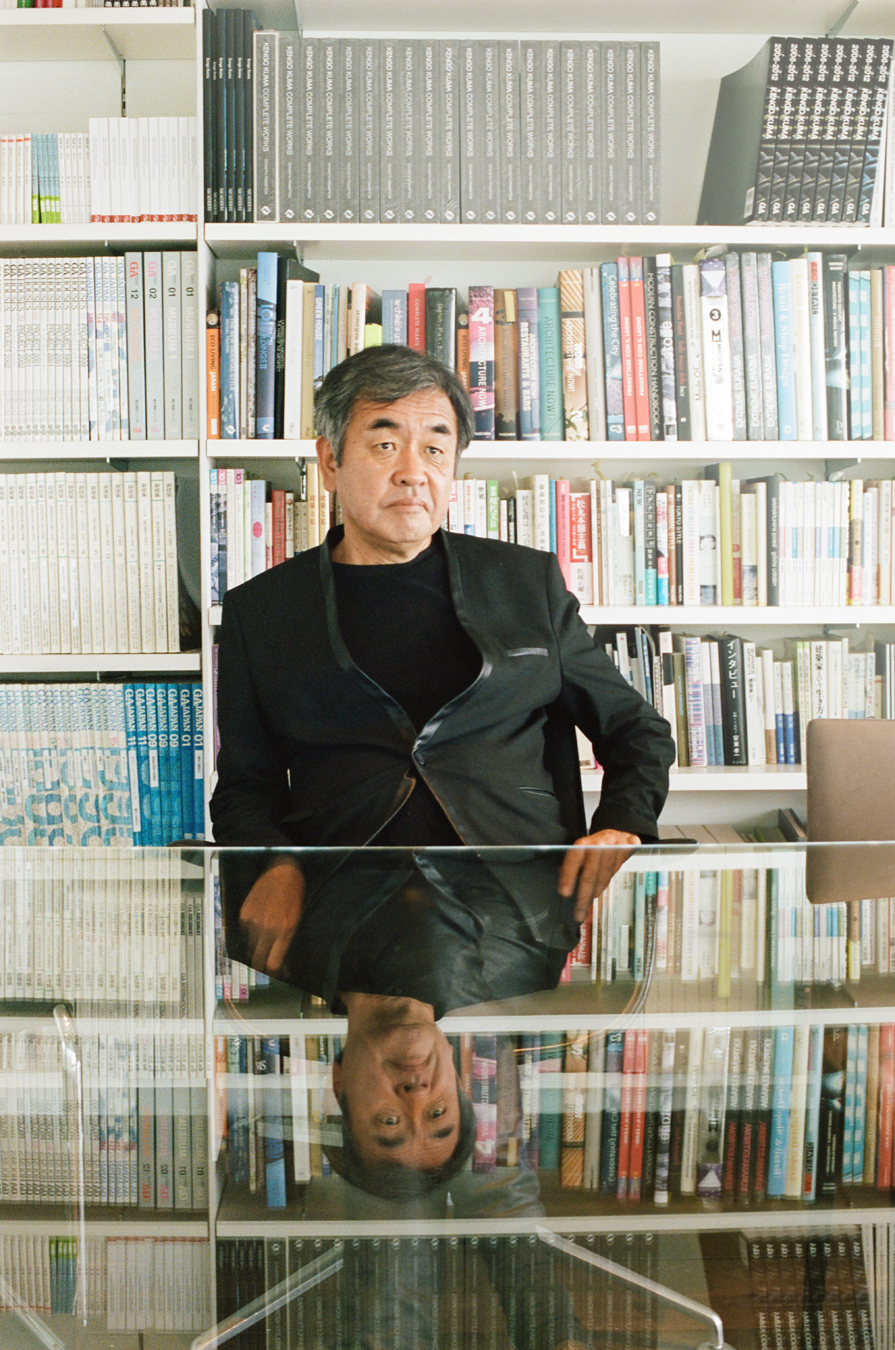

Kuma is a master architect, a title reserved for very few in the world and earned with an extraordinary portfolio of outstanding projects of all sizes, in Japan and now across the globe. Even after practicing for decades, I still find great architecture hard to describe in words. Kuma’s Fujiya conjures a feeling rooted in the limbic system, where emotions are born, though language to explain them does not exist. Kuma’s architecture, like all great architecture, can inform our emotions; it can calm, it can quiet, it can help us reflect, it can draw us together, and it can create joy.

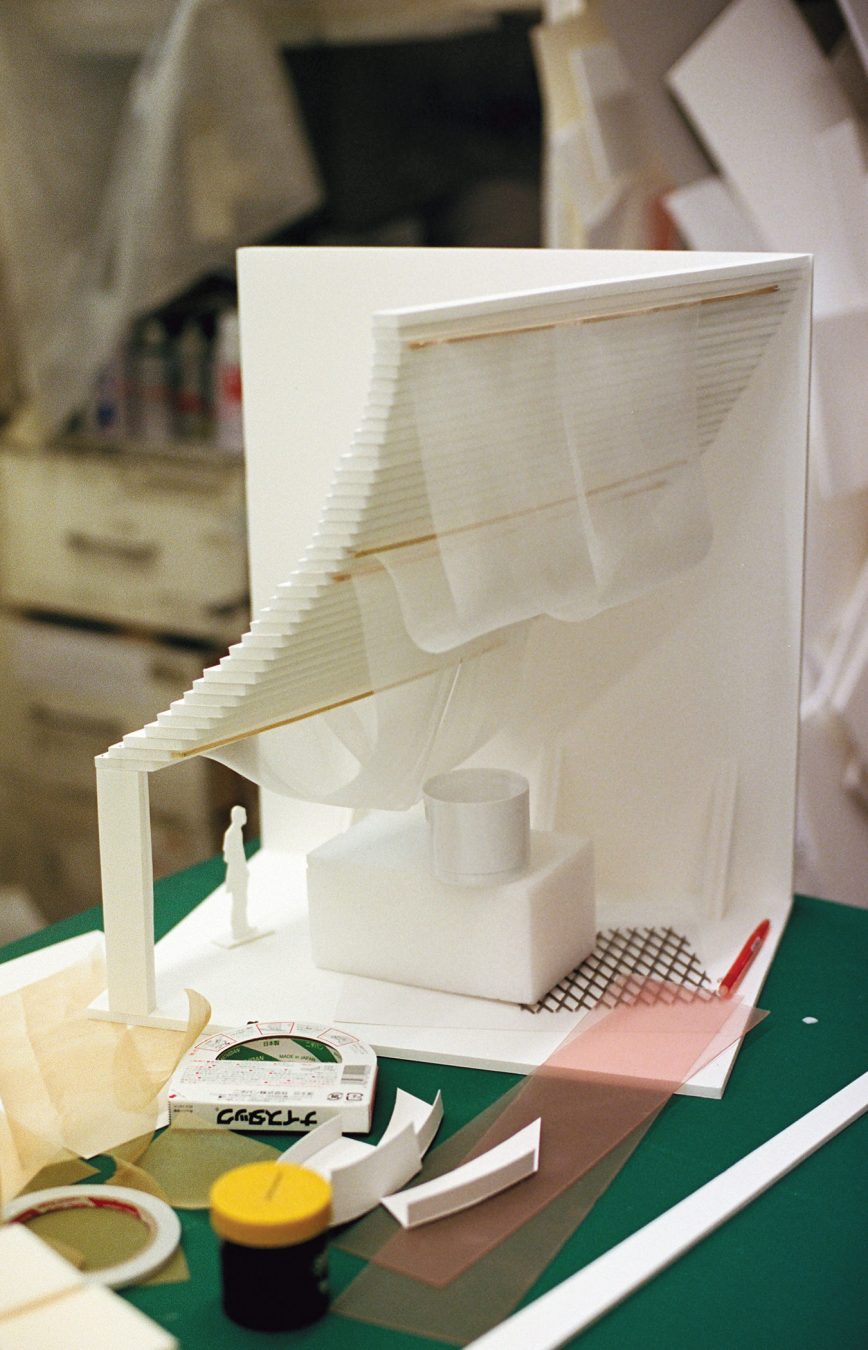

He speaks about the modest scale of his early work in the context of the depressed Japanese economy, when he first started to practice. That early work clearly remains important to him, while his practice and projects have grown considerably in size. “I would say our approach is fundamentally the same,” he says. “With any scale, I always start with the details. I think about the materials and the members; how the characteristics of the constituents could aggregate to create a whole.”

Often his materials are picked from the site, like a master chef foraging for delicacies. Stone laid in stratified layers mimicking the Scottish sea cliffs sculpt the walls of his V&A Museum of Design in Dundee, Scotland; for the China Academy of Art’s Folk Art Museum in Hangzhou, Kuma found stone and clay tiles from old homes in the area to honour the past, and contextualized the project with artfully woven grey tiles that create screens to shade and wrap the building forms. Kuma’s sensitivity and ability to respect the past and present inhabitants of a place, as well as its natural context, is what sets his work apart from many global architects. His desire to understand natural forces and systems, and our relationship as humans to these forces, gives his work longevity beyond the fashion of this day.

The thread that connects Kuma’s work, from small to large and from house to gallery, is his subtle crafting of a sensory experience, through textures and ingredients, composition, sound and light, and, mostly, from a modesty built on passions more informed by exploring a meaningful architecture for humanity than an architecture of fame or fortune. He says, in his calm, thoughtful way, “Lately, I have come to realize that architects either fall into the ‘corporate’ or ‘artistic’ categories. These are almost independent professions, operating with very different results. I have always felt I do not belong to either because they both lack a sense of social responsibility. I want to explore a third route, one that simultaneously responds to the needs of the people and develops design with local craftsmen and inherited wisdom. Wood is an emblematic material for this—it has always been the source of shelter in Japan, prior to the emergence of the corporation or even the artist.”

He is now over 60, and his practice is evolving quickly. This change offers interesting insight into the challenges of an architect known for hands-on exploration of materials from the land, creating the context of his projects. In 2015, Ian Gillespie of Westbank Projects Corp. commissioned Kuma with the intent of bringing a new sensory experience to Vancouver architecture. Here, Kuma faces new challenges in his first major tall tower project in North America. Westbank’s Alberni by Kuma is a 43-storey residential building near Stanley Park, and the project is a turning point for Kuma in many ways. His status as a master is set, and now it is time to manage a growing practice and the demands that come with success.

“With any scale, I always start with the details. I think about the materials and the members; how the characteristics of the constituents could aggregate to create a whole.”

To be a master architect, you have to be exceptional at so many things. You have to bring design that resonates with the public’s ever-shifting aesthetic and social, cultural, and economic values. You have to connect with a concept that speaks to all senses. You have to be a communicator, salesman, and marketer for your ideas to even find a willing patron, and you must conduct an orchestra of designers, engineers, contractors, and policymakers often for years to realize your vision. Finally, you must find time to be creative, inspiring, innovative, and passionate. You must deliver every time, because you are only as good in the public’s eye as your last project. Over and over again you must mix design, politics, policy, ambition, personalities, context, values, history, natural forces, sensitivity, and integrity in an ever-spinning bowl to have a hope of success, and then—and only then—can you sit and watch your work rise. And hope you got it right.

As architects, we share roots with those who came before us, who inspired us or mentored our perspectives and our work. Who were Kuma’s touchstone architects? “Kenzō Tange is considered the leader of the first generation of architects in Japan. I sought to become an architect when I was 10 years old, upon seeing Tange’s Yoyogi Gymnasium for the 1964 Olympics,” Kuma says. “His design represented a new age that was expressed in concrete, a gesture of strength and optimism. But having seen the recession in the 1990s, and the earthquake in Tōhoku and more recently in Kumamoto, I have come to feel that this confidence is an illusion, that we are in fact vulnerable beings that are in need of an improved dialogue between individuals and with the environment. This sensitivity is what I mean by ‘small’ architecture.” At times Kuma has studied socially-conscious projects that search for solutions to challenges. His conviction is that there is a broader need for an architecture that serves humanity. He affirms his rationale: “I certainly feel it is our obligation to connect with the people and the environment to offer something that is socially meaningful.”

What Kuma creates next will be exciting to see. He is powered by a desire to research, grow, and learn, and to make a difference to the community he serves. He explains: “My motivation is always to engage in a new kind of project in a new setting. I want to deepen my understanding of different cultures, and I want to offer some inspiration through my design.” Architecture is more than the decoration it is often seen as. In part, it is about affording everyone the transformative experience of truly great buildings that shape our social and cultural experience—buildings that engage our spirit and our senses.

________

Read more from our Design section.