Imagine that it is 1915 and you are living in Paris. The doorbell rings. The butler answers, takes charge of a package, and brings it to you in the drawing room. It is a small rectangular case, about the size of a shoebox or a generous container of chocolates, sheathed in that familiar brown monogrammed canvas. You lift up the lid, and discover not footwear or sweets inside, but rather a bouquet of impossibly fragrant and vivid roses. They are not staidly lying on their side, as is convention when one is sent flowers—they are practically bursting forth from the case, which has been fitted with a rectangular vase of water.

Georges-Louis Vuitton’s Malle Fleurs—which was brought back in 2015 for its original function as a flower trunk—was only one of the many ingenuities produced by the Louis Vuitton workshop in Asnières-sur-Seine. This has been the ancestral atelier since Georges’s father, Louis Vuitton, moved the family and factory out of Paris in 1859. Absolutely everything Louis Vuitton was made here until 1977, and even now, it is one of only a dozen of the company’s production facilities around the world. If, like Yves Saint Laurent, you covet a special carrying case for your Pleiade books, or, like Damien Hirst, you desire a particular trunk for surgical tools, you enter into the rarified Louis Vuitton world of custom-ordered, hard-sided luggage. And for that, to Asnières you must go.

Other than the fact that it is on Rue Louis Vuitton, there is no sign that the small building at the end of this quiet street is the historic headquarters of the luggage-maker. The dark brown door is unmarked. Above the walled garden in the back, one glimpses treetops and the gabled roof of a tall cottage with white brick and grass-green shutters. But walk through the door, and you find yourself in the family home where five generations of Vuittons once lived. There is a painting of the patriarch next to the front door. In the living room, with its ceiling moulding of floral flourishes and intertwining tendrils, are framed family pictures; the organic curves of the ceramic fireplace seem draped in glossy blue enamel. Sunlight comes in through Art Nouveau stained windows that look out onto the lawn. A billiard table stands in the middle of the room, ready for the next game, and a Malle Fleurs with a fresh bouquet sits on the coffee table.

Patrick-Louis Vuitton, who is Louis’s great-great-grandson, moved out of this house in 1964, but he still directs the tranquilly bustling atelier of 200 workers. This is where special orders, trunks, and prototypes for collaborations like the recent Louis Vuitton-Supreme collection are produced. The three-storied factory next to the house is in the glass, steel-girdered, barrel-vaulted roof style of the turn of the century. Here, one can follow a python Capucine handbag through every one of the 300 steps required to make it, or survey the journey of the Malle Fleurs, which starts out in the carpenter’s workshop as a humble, bare beechwood box and lid.

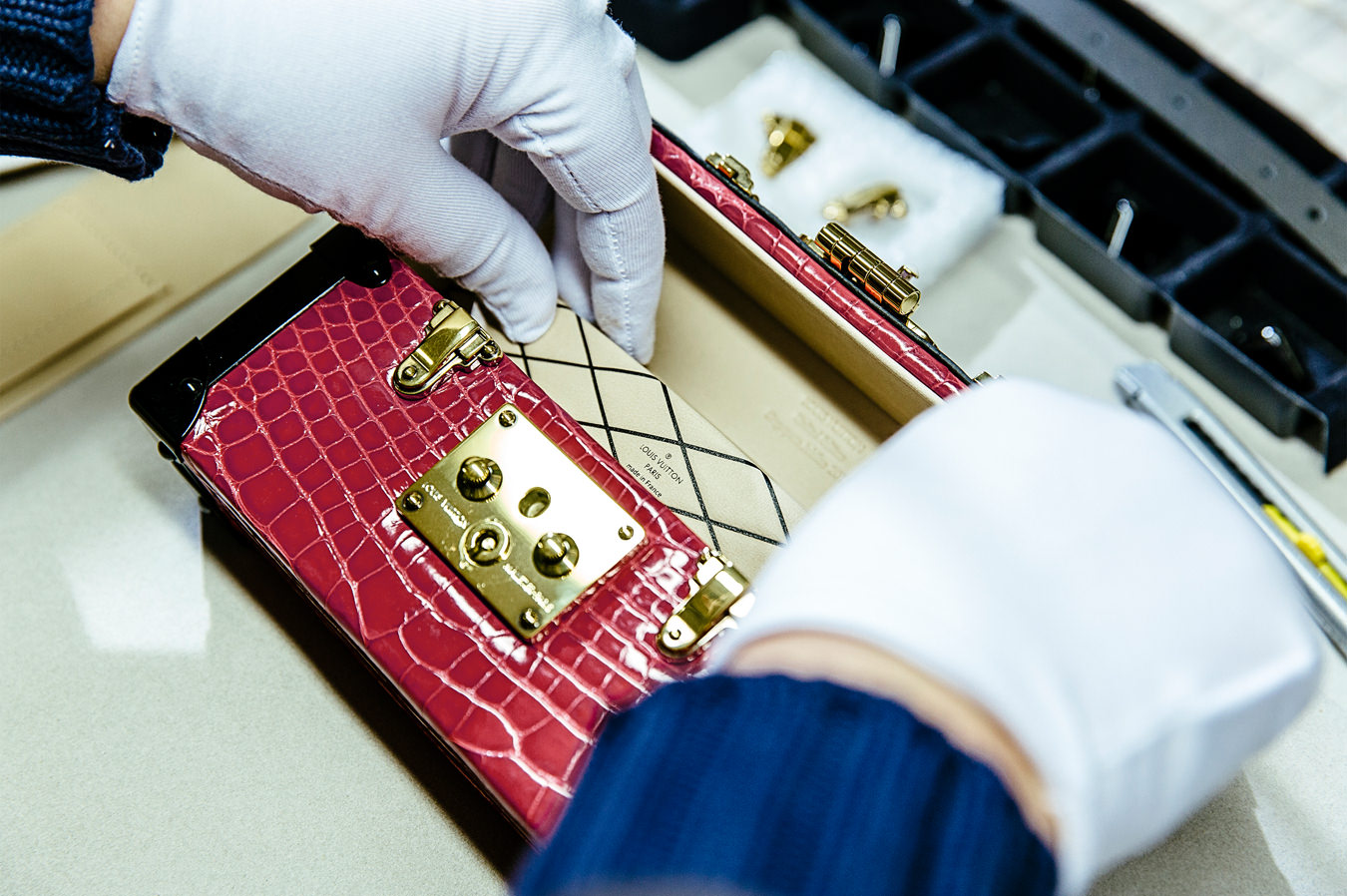

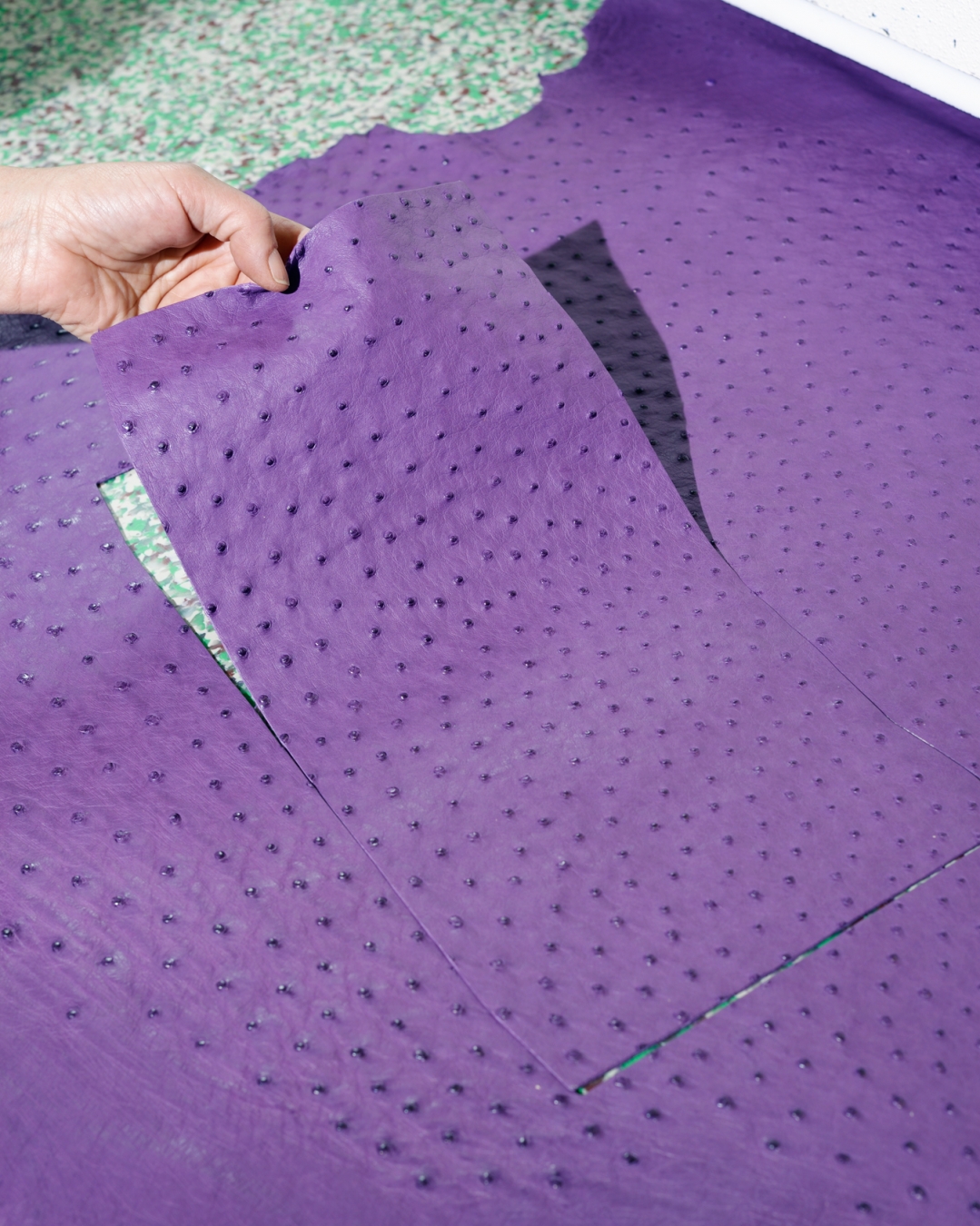

Here, artisans are always busy. A woman peers at a screen on one of the huge cutting machines and pushes a button, and robotic arms manning tiny precision box-cutters spring into action. This is where the rolls of varnished Epi leather that creative director Nicolas Ghesquière loves so much, the Damier and monogrammed canvas, the exotic crocodiles and stingrays, and the vachetta cowhide that Louis Vuitton has used since 1860, first go under the knife. At various stations, employees in almond-white lab coats or dark blue aprons are re-cutting the pieces to meticulously fit each case. They painstakingly glue them onto the wooden boxes, making minute incisions to perfectly wrap them around corners. Like wallpaper, the pattern has to be seamlessly continuous, and the Louis Vuitton logo is integral.

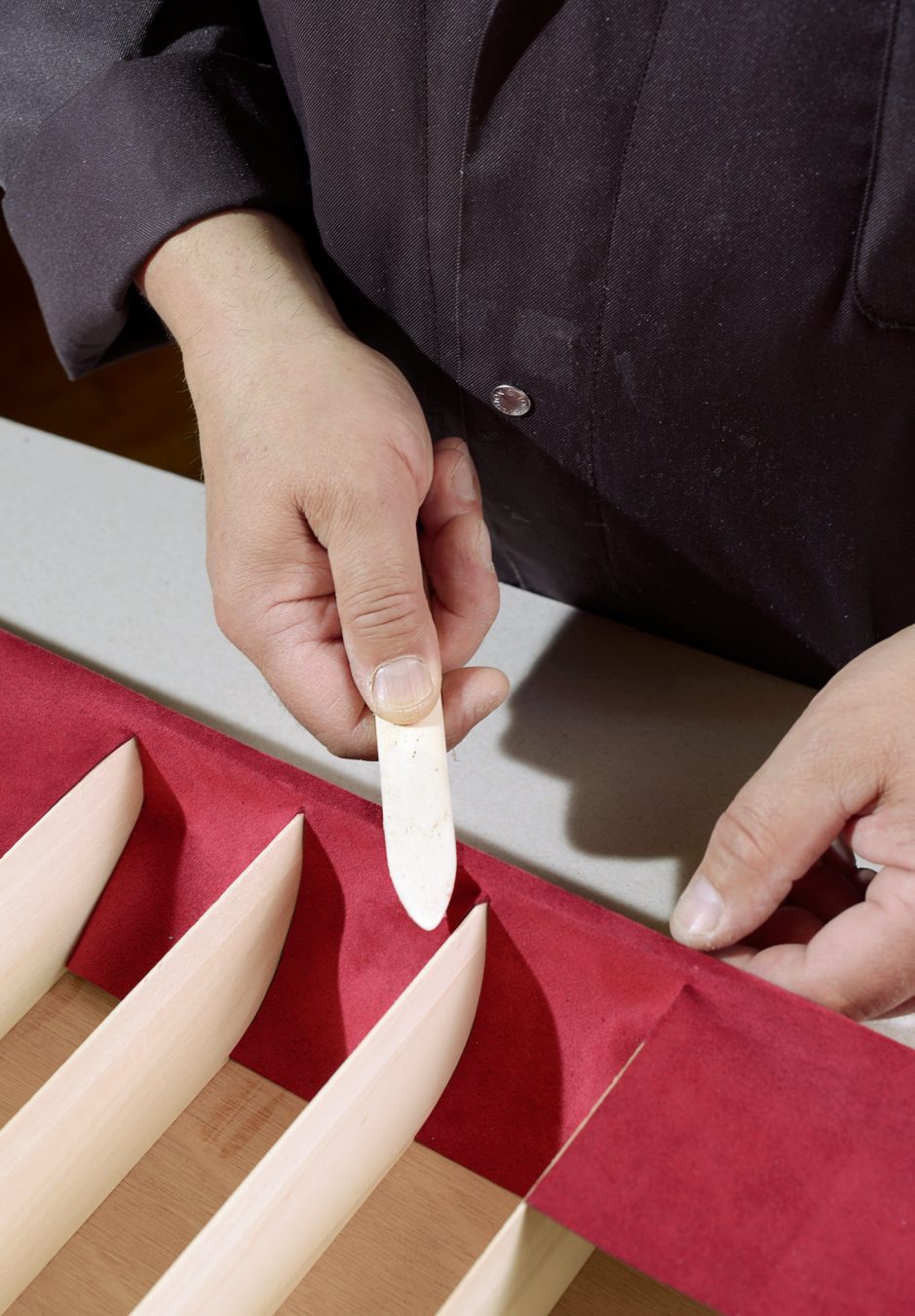

One artisan, who is a brand veteran of 33 years, is putting hinges on a customized pen-and-ink case. The hinges are an insurance measure for the material that really holds the lid and case together: a rectangle of simple white cotton fabric called the nervurage with a seam down the middle. Glued to the inside frames, it is the inventive “connective tissue” in every case. Another worker then selects a small hammer from the customized toolkit sitting next to his desk. It is the size and shape of a trombone case, and its lid is decorated with his initials and a tattoo-like pattern of patinaed brass nails. Carefully laid inside the cushioned compartments are the tools of his trade. The handles are sheathed in the supplest red leather.

In another room, one person is nailing brass tacks and gleaming hardware onto an empty trunk while another builds the interior compartments for it next door. The trunk is roughly the size of a small refrigerator, and is to be outfitted with numerous drawers, each for one of the client’s collection of automatic watches. The artisan says that, occasionally, a client will request secret compartments, or even a false bottom in a case. He says he never asks what they’re for.

Discretion is, of course, paramount within these walls. Privacy is as fiercely guarded at Louis Vuitton as the secret of the stitching on its bag handles. As with all things truly luxurious, what we don’t know is infinitely more compelling than what we do. There is talismanic power, for instance, in the unseen initials that some of the craftsmen pencil onto the wood interior structure of each case. Like the brown door on Rue Louis Vuitton that so many walk past without noticing, the savoir-faire in the making of each case and trunk is mostly unnoticeable. But to initiates, to whom Asnières is a place of pilgrimage, nothing is invisible—they know exactly where to look.

Get a copy of our Summer 2017 issue delivered right to your door.