Still, it is hard not to be skeptical. On the eve of one’s own birthday and deep in the slow, terrifying car crash of the current global political climate, what, really, is the likelihood of anyone feeling “not so serious”?

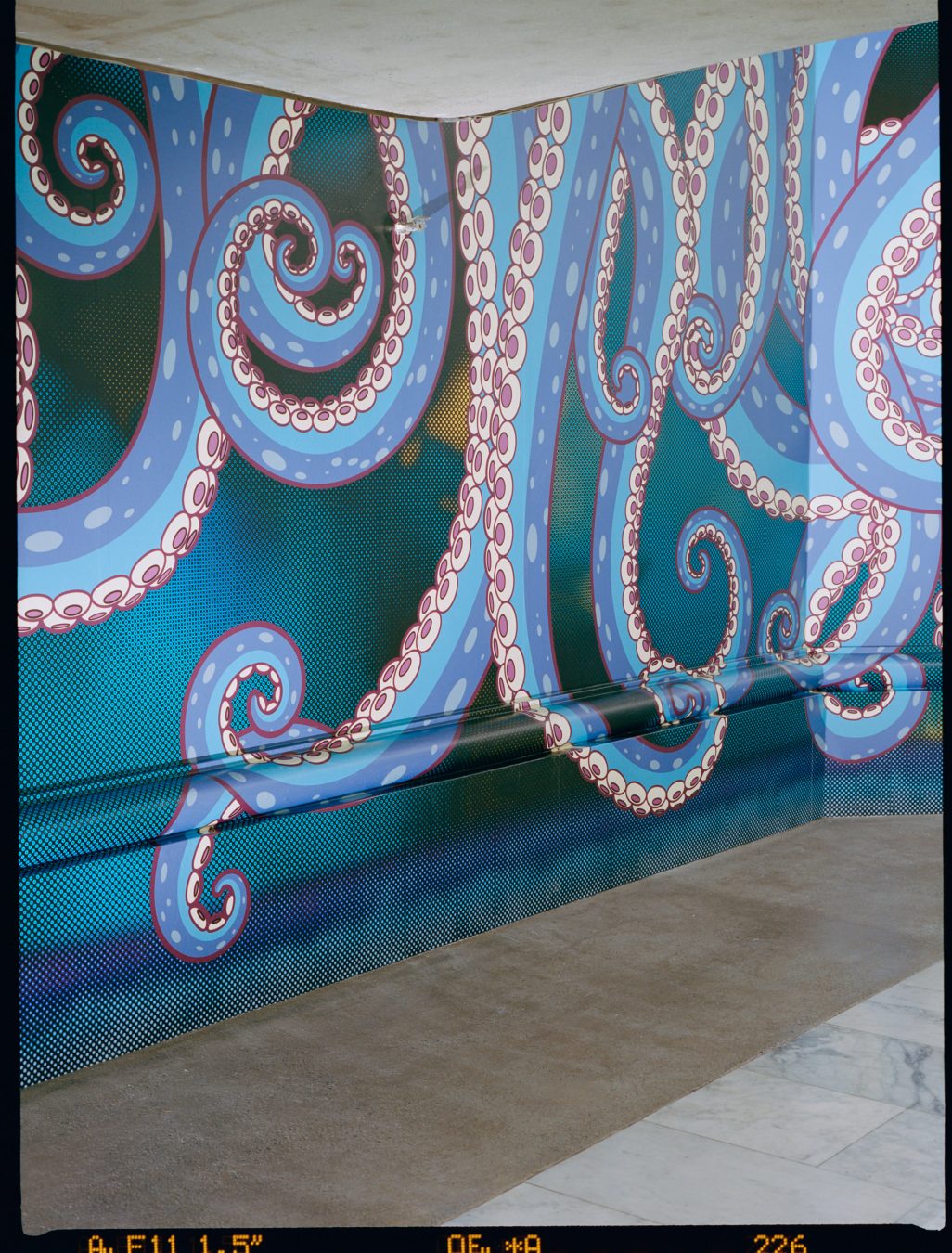

In-person, Murakami is polite and jovial, gamely posing for photo ops and cracking jokes; yet he is somehow also reserved (or perhaps just very jetlagged). There is a deft lightness to Murakami, the man and his artwork, that seems at times equivocal. Case in point: the glittering tentacle-patterned outfit he wears, made to match the wallpaper he designed for the gallery’s atrium, allows him, oddly, to blend into his surroundings. Murakami is clearly adept at having it both ways, being a wallflower and a showman: his art and image are rooted in contradictions. Famously, he helms a large studio to keep up with the demand for his art, where assistants work around the clock to execute his ideas. Murakami is in command of a vast creative machine, all while envisioning himself an outsider.

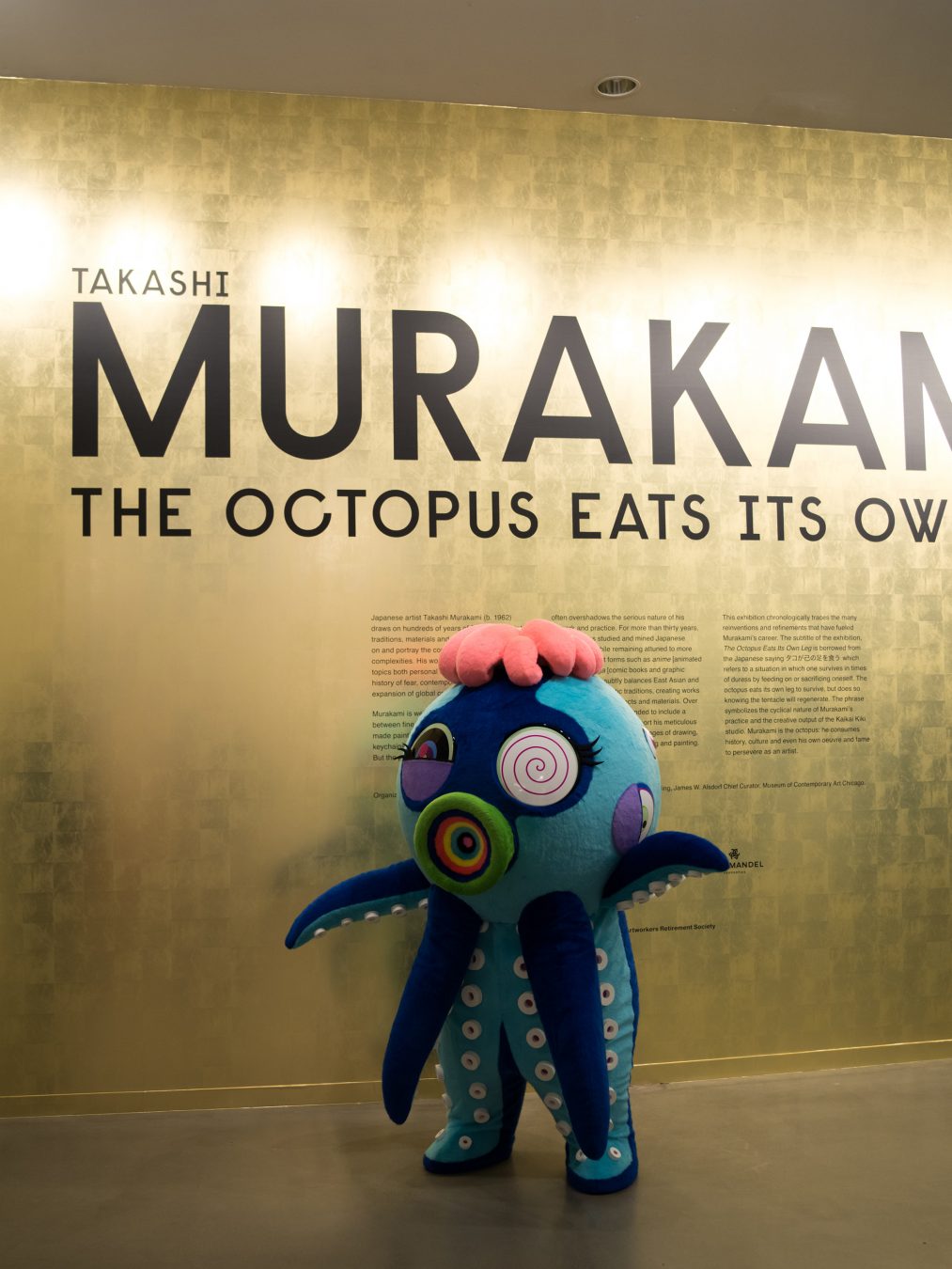

There is the matter of his blockbuster retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery, “Takashi Murukami: The Octopus Eats its Own Leg,” which ran from Feb. 3 to May 6, 2018. Of the exhibition title, he again emphasizes that “not so much serious thought went in to this. It is all about my own lack of talent and how I feel really sort of embarrassed and sad in my daily life because I have to keep recycling old works to create new works.” A distressed octopus can, as a last resort, chew off a compromised leg and survive, able to eventually regenerate the missing limb. It’s hard to think of a more apt image of persistence in an inhospitable world, though that appears not to have been the artist’s intention. “Once it becomes an exhibition title, of course people put a more social connotation on it,” he says through a translator. Murakami lets his work speak for itself, and such vibrant, evocative imagery is at least as loud as the artist’s own stated intentions. Surely this is not an accident.

In fact, nothing in Murakami’s world seems accidental, so finely tuned are the mechanisms of production, so glossy and precise is his output. Even his current position as one of the world’s best-known contemporary artists is the result of clever planning. Early on, Murakami saw how difficult it was to forge a stable career in the Japanese art market and resolved to build his reputation abroad. After studying Nihonga, a traditional Japanese painting style, he began exploring the characters and preoccupations that would become his signature (a peppy, animated mouse-like creature named Mr. DOB and a sinister, skeletal mushroom cloud, for instance). Murakami hit his stride in the late 1990s and, thanks to a tireless work ethic and a gleeful engagement with consumer culture, has remained unrelentingly relevant ever since. A survey of his output, starting in the ‘80s and continuing, unbounded, into the present day, can read like a gauntlet of visual nostalgia. The early 2000s are particularly vivid; few can remember the fashion of those times without the concurrent longing for a Louis Vuitton by Murakami shoulder bag or hear Kanye West’s Graduation and not visualize Murakami’s purple album cover design.

If he insists that he sees himself as an octopus, consuming and repurposing his own body of work, it is fitting, then, that the notoriously self-cannibalizing fashion world has embraced him. Today, Murakami appears in a pair of unreleased Nike Air Jordan 1s produced in collaboration with Virgil Abloh’s cool-kid streetwear brand Off-White (and given to him by Abloh himself as a birthday gift). This affiliation with Abloh is Murakami’s latest in a series of successful fashion matches—the two worked together on an art-meets-style project at London’s Gagosian Gallery—but, according to the artist, it is uniquely fateful thanks to a series of near-associations (Abloh was the creative director for West’s Graduation, and Murakami met him, fleetingly, on a studio visit many years ago). Murakami has been determined, throughout his career, to set himself at the nexus of trends, so it’s only natural he is now in step with some of the world’s most covetable brands.

He is a deft social analyst, after all, seemingly delighted with and intrigued by popular culture. He underscores many of his points with images from Instagram, whipping out his phone to reference viral trends such as Kim Kardashian’s Yeezy Season 6 campaign. Octopuses are known to change the colour and even the texture of their skin to suit their surroundings, and Murakami has settled into a similar role—part Shakespearean fool, granted the unique privilege of mocking the ruling classes, and part consumer algorithm.

His playful iconoclasm is best embodied in Superflat, a theory, later movement, conceived by the artist as a great levelling of high and low culture. It is difficult to even the playing field without first toppling the highest echelons of it, and the art world’s unbridled enthusiasm for Murakami has a slight air of defensiveness combined with admiration. It is impossible to tell if Murakami, with his canvases reminiscent of commercial graphic design and the booming merchandise business, is exalting consumerism or knocking high art down a peg.

Popular appeal rarely dovetails with white cube sensibilities, but Murakami’s work is an exception. His exhibitions break attendance records, and they attract fashion kids and sneakerheads just as much as art types. “I am really interested in these little incidents and news that go viral,” he says. Interestingly, viralness—the proliferation of a single image or idea that spreads because it is highly relevant and widely relatable—has been a present in Murakami’s work since before we had a name for it.

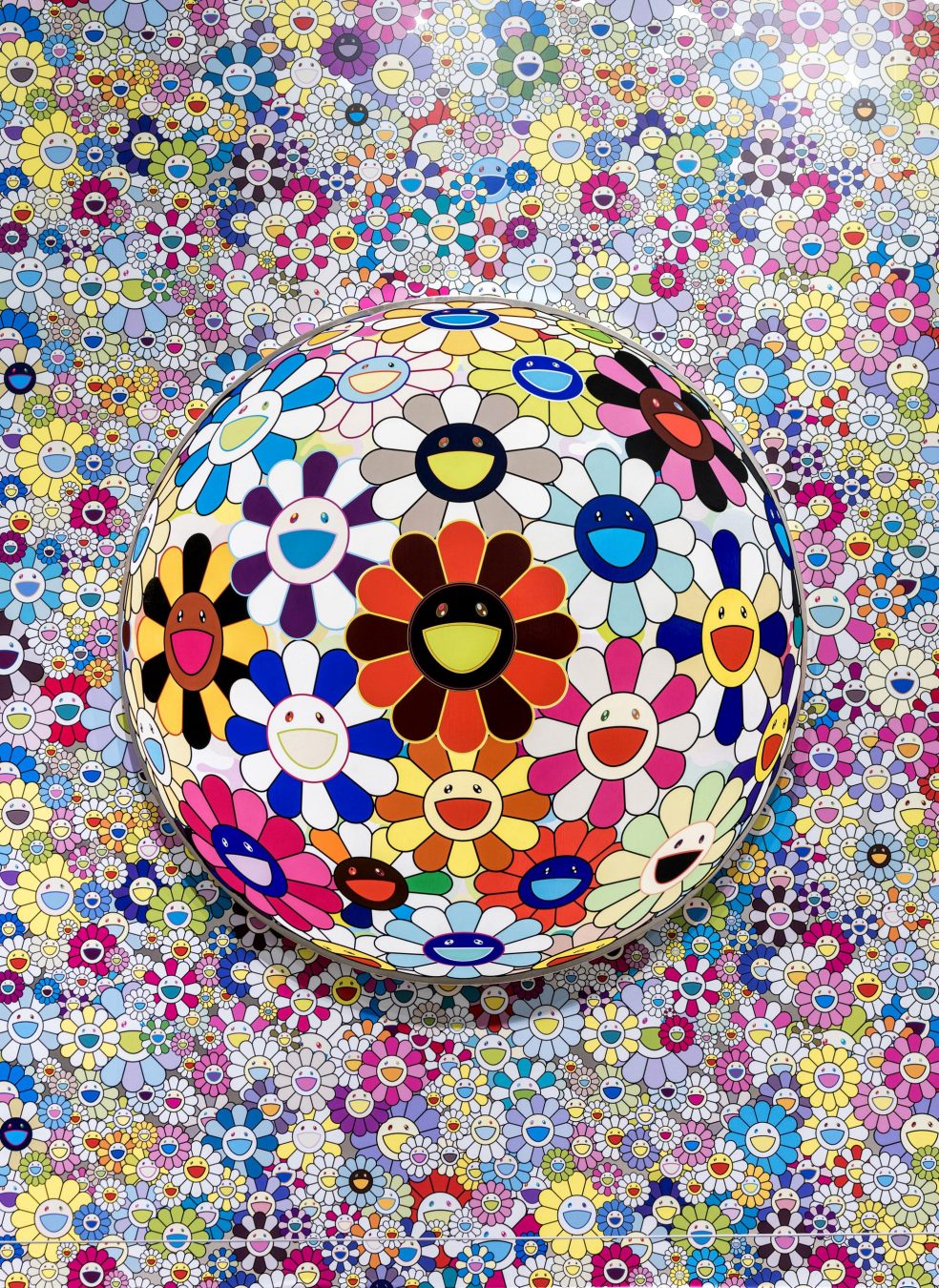

Herein lies the secret to his mass appeal: an eerie ability to reduce an era into an image. Reading his output as a yet unburied time capsule, his unnerving blend of playfulness and deep anxiety becomes our own. He may be “pursuing more lighthearted, slapstick themes,” but his legacy is made of spirit interspersed with anguish, as contemporary a combination as one could have. It takes great conceptual dexterity to develop imagery that is equally successful as a selfie background, a children’s toy, and a statement of nuclear angst. His most famous motifs—a dense field of smiling flowers; psychedelic, googly-eyed mushrooms; multi-coloured skulls—all work their way into our consciousness as sweet confections and linger there by virtue of their ominous undertones. No matter how cheerful a cartoon mushroom, the word “cloud” trails closely behind.

Discover more from our Arts section.