The ’60s ended a half-century ago, yet they live on in the fertile imagination of Bob Masse.

The celebrated artist, known for his glorious psychedelic concert posters, is as busy as ever in his Salt Spring Island studio. When not on the computer creating new images in Adobe Photoshop, he’s stuffing mailing tubes and boxes with vibrant prints to send to customers around the world.

Back in the day, he crafted posters for the chance to get backstage and hang out with musicians. Sometimes he was paid $10, other times nothing at all. The posters were slapped up around town and promptly forgotten.

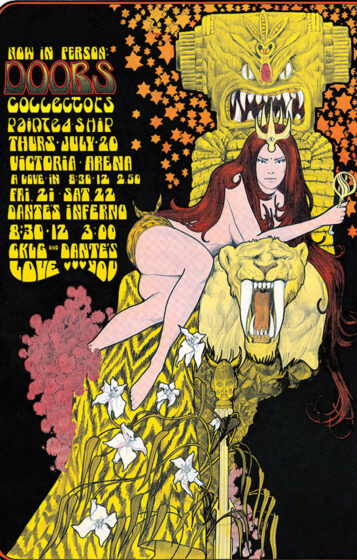

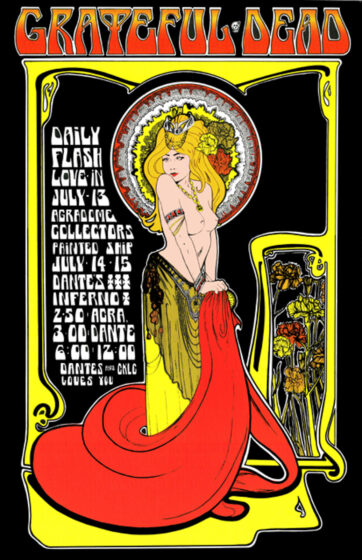

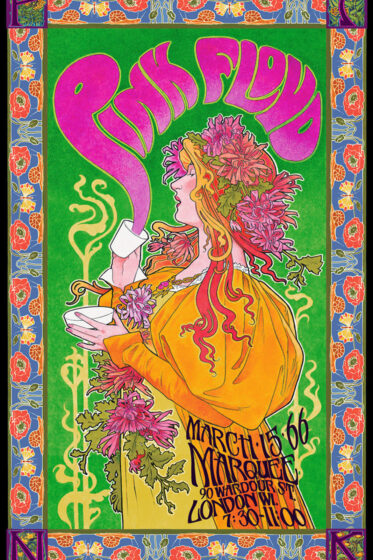

He is known for ornate art nouveau–inspired borders featuring flowing flower stalks that surround nymph-like women in various stages of diaphanous undress. The band’s name and the venue are rendered in far-out lettering. The posters catch attention in garish greens and pulsating purples. Today’s versions are a little less druggy, though just as groovy.

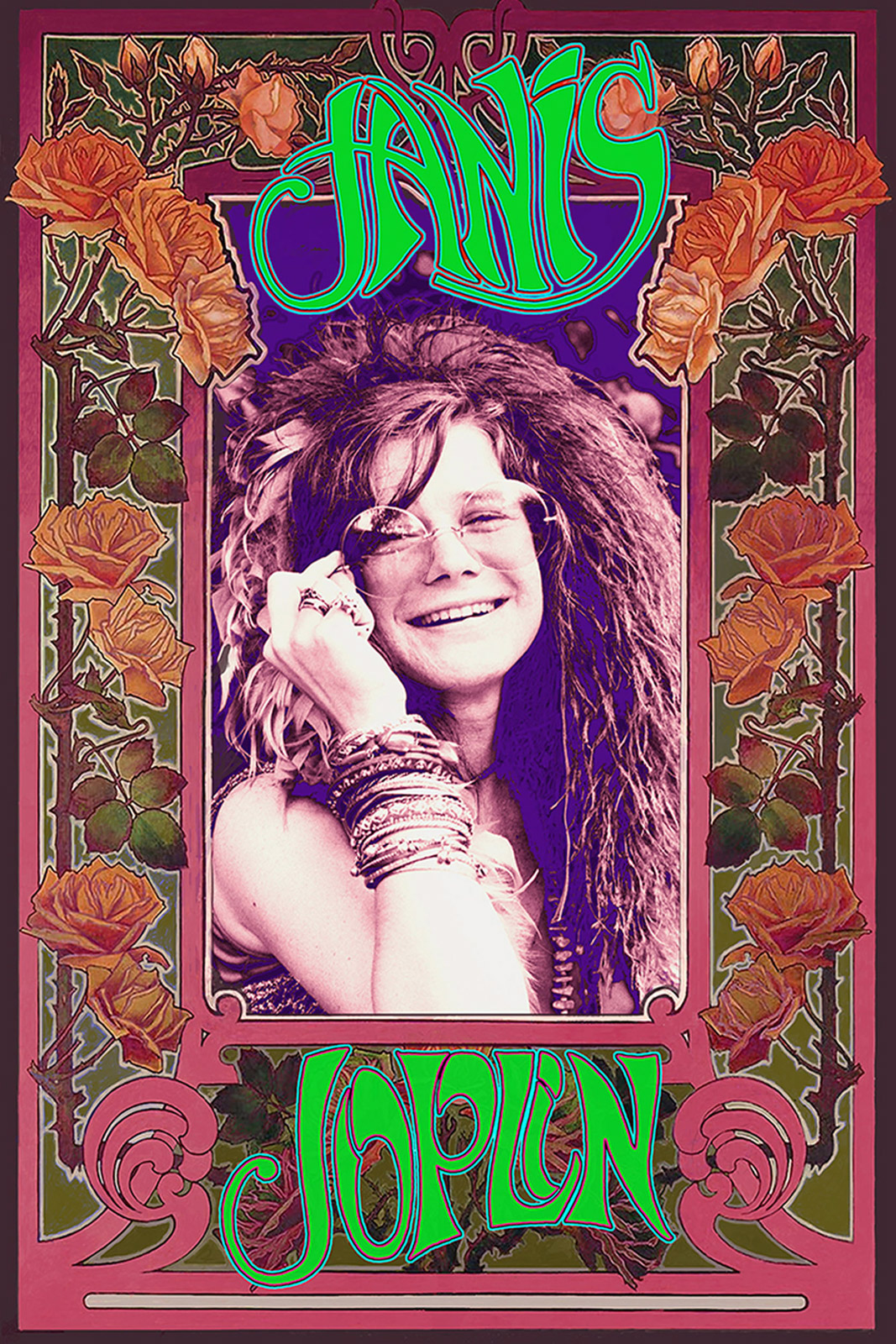

“I’m just finishing a new Janis piece,” Masse says on the telephone, the shriek of packing tape punctuating his sentences as he multitasks. “I’m working on an Aretha Franklin. I just did a David Bowie.”

He lets the news linger. “I work for dead people,” he giggles.

For some, the ’60s remain more alive than the musicians he illustrates. His new work, licensed by a New York agency, is still as eye-catching, the lettering more legible and more often rendered in soothing aquamarine tones. He says he is busier than ever in this year of the virus, as lockdowns and internet access have exposed his work to new customers around the world. Just the other day, he had orders from France, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, and Puerto Rico. Who buys Masse? “Young kids who want to decorate their campus dorm walls to people who will pay a couple of hundred, or even a couple thousand.” Those are substantial sums for what was once considered ephemera.

It has been, as the Grateful Dead noted, a long, strange trip: Masse is the son of Lill and Joseph Masse, an army veteran and furniture refinisher who supported a family of four children as a Woodward’s employee. The Masses lived in Burnaby, and young Bob attended the old Vancouver School of Art in downtown Vancouver. As part of his studies, he had to do commercial work.

He crossed the street and offered to do free posters for the Queen Elizabeth Theatre. As it turned out, the young impresario Howie Bateman was presenting a show featuring a 23-year-old protest folkster from Minnesota via Greenwich Village. The tousle-haired singer had just released his fifth studio album, Bringing It All Back Home, which would prove to be one of the most influential releases of the decade. Masse created an attractive poster featuring black-and-white photographic portraits of the singer over his name in capital letters: BOB DYLON. The poster had been displayed all over town before anyone noticed the egregious misspelling.

Despite that unpromising debut, the budding graphic artist soon became the poster-maker for the Afterthought, a music-and-light show put on by teenaged promoter Jerry Kruz. Once again, Masse made his breakthrough by offering to do the first one without charge. He also created posters for the Retinal Circus, a club on Davie Street.

He remembers first seeing in the shop windows along San Francisco’s Haight Street the outrageous lettering and bold graphics used by an artists’ collective known as the Family Dog. This new age of artistic expression allowed Masse to indulge his love for art nouveau and, later, the imagery of Alphonse Mucha, the Mitteleuropean artist renowned for his turn-of-the-century theatrical posters of the great Sarah Bernhardt.

When the Vancouver rock band the Collectors went to Los Angeles to record, Masse joined them, signing with Warner Bros. to produce album covers and settling into leafy Laurel Canyon, where a passerby might hear Joni Mitchell plinking on the piano in her home. There, emerging rock stars were ordinary people, and Masse an amiable behind-the-scenes figure, though in hindsight he sometimes wonders how he wandered into “strange scenes for some guy from Burnaby.”

Masse befriended many, including Janis Joplin. (He regrets not having taken the hint when she complained about the lack of male groupies. “Nobody chases me,” she told him. “I’m not getting any action here.”) He made posters for the Dead (as in Grateful), the Airplane (as in Jefferson), the Mac (as in Fleetwood), not to mention the Doors, the Byrds, and the Yardbirds, as well as Iron Butterfly and Vanilla Fudge. In those heady days, he painted a mural for the Potpourri Head Shop in Fullerton, a popular stop for students attending the nearby campus of Cal State.

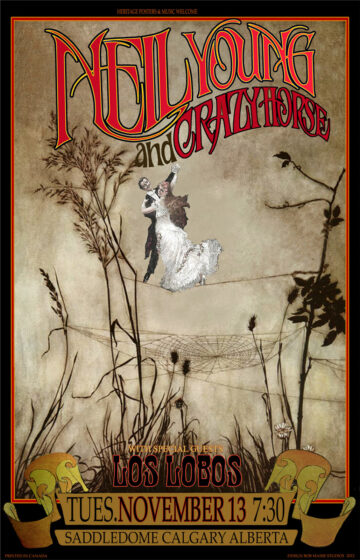

Still, it took decades before psychedelic rock posters were considered anything other than toss-away doodling. Masse continued to make concert posters through the 1970s, though in a less florid style. His work was everywhere, yet often unacknowledged. (Among his creations—the once-ubiquitous orange cartoon fox mascot for rock radio station C-FOX.)

A revival of interest in classic rock posters in the early 1990s found him once again an artist much in demand. He revived his signature style to create intricate posters for the Vancouver Folk Festival, the 25th anniversary of the Stanley Park Easter Be-In, and the 30th anniversary of the Summer of Love.

Tie-dye is enjoying a comeback, pot is legal, and the art of Masse continues to blow our minds.

This article is from our Winter 2020 issue. Read more Arts stories.