The year 1974 was one of the nuttiest in North American political history—ignoring our current era, perhaps. Fifty years ago last August, U.S. President Richard Nixon resigned to avoid impeachment. Throughout the fall, disgraced former attorney general, John Mitchell, was sweating in a federal courtroom on charges related to the Watergate break-ins. And on a cold October day, a very different John Mitchell walked into Vancouver city hall to nominate a tap-dancing peanut for mayor.

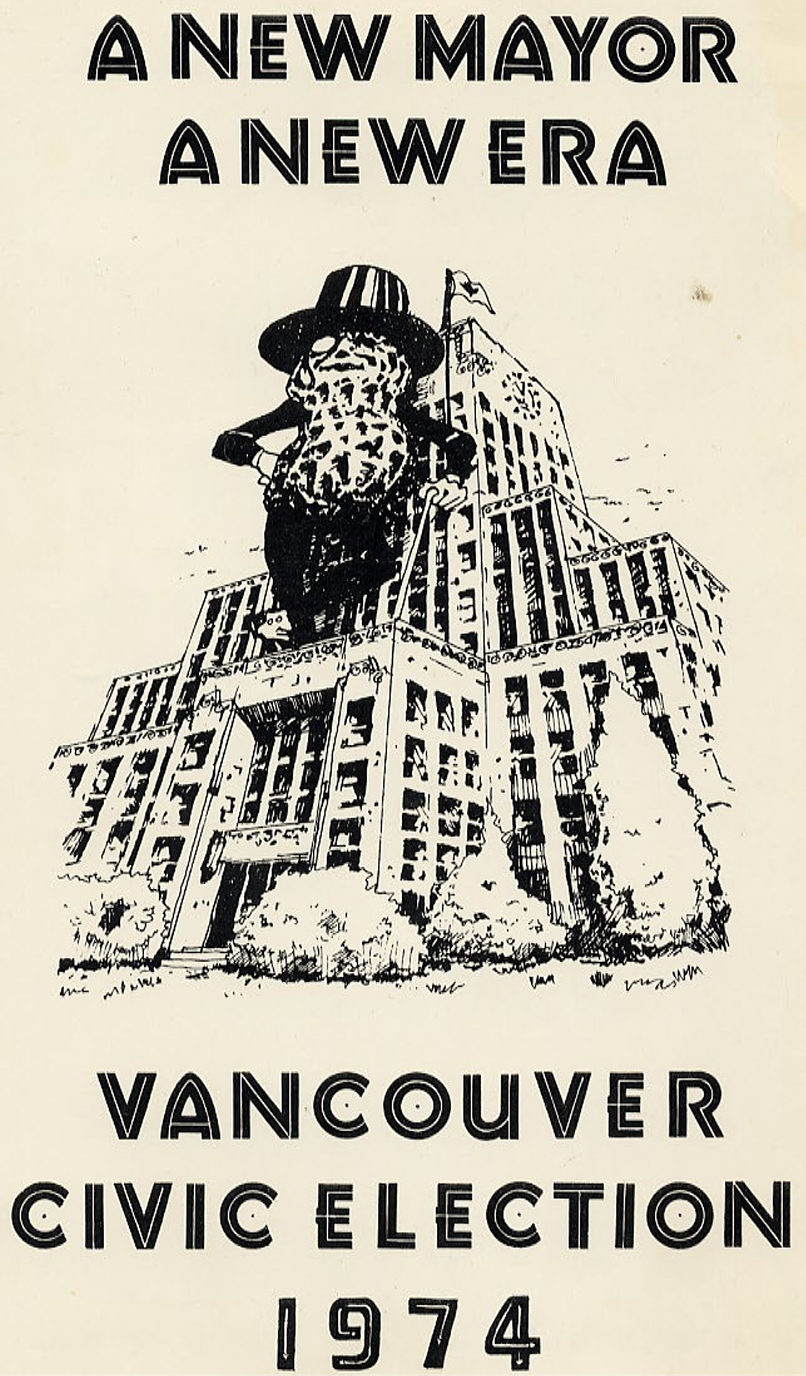

“Returning officer Doug Little, looking somewhat out-of-sorts about the whole matter, certified [Mr. Peanut] as a candidate,” The Province wrote on October 31. “[Peanut] kept his costume on during the certification process, but did remove his tall black top hat to get into Little’s office. Spats, black tights, and a cane completed his attire.”

The project was the brainchild of artist Vincent Trasov and sculptor John Mitchell (founding members of the legendary artist collective The Western Front Society), and over the course of the campaign, they thrilled voters with their surreal take on politics, performance, and culture, which would resonate—for good or ill—for years to follow.

“It was a 20-day performance,” Trasov recalls, speaking on the phone from his home in rural Germany. “I was an official candidate. They couldn’t dismiss us or say we weren’t part of the mayoralty campaign. They had to give me time. They had to give me the stage.”

With a campaign budget of just $14 (plus $300 required for nomination paperwork), a five-piece band, and six backup dancers called the Peanettes, Mr. Peanut, under his Peanut Party banner, danced his way through candidate events from East Vancouver to Point Grey, running on a platform of “Performance, Elegance, Art, Nonsense, Uniqueness, and Talent.” As opposed to the other candidates—incumbent Art Phillips, notorious NPA grump George Puil, and NDP hopeful Brian Campbell—Trasov kept silent on the campaign trail, with candidate literature stating firmly: “Mr. Peanut will be unavailable for comment now, during, or after the campaign.” Nonetheless, he developed a following and garnered tongue-in-cheek endorsements from newspaper columnists Alan Fotheringham, Bob Hunter, and James Barber.

“There were no real serious issues in that campaign,” Trasov explains, “so we were able to talk about art, and politics as performance, and how important it was to have some culture in the city. Back in those days, culture in Vancouver was just beginning.”

A campaign poster promoting Mr. Peanut for mayor.

Trasov, then 27, was at the start of his artistic career, but his association with Mr. Peanut—appropriated from the iconic mascot designed for the Planters Peanuts company back in 1916—predated the campaign by many years.

“I had a Mr. Peanut colouring book as a kid,” Trasov notes. “I had started doing drawings of him, and initially I just wanted to do some animations of him tap dancing. But that required too much time, so I thought, Why don’t I make a papier mâché costume? So I was able to animate Mr. Peanut that way instead.”

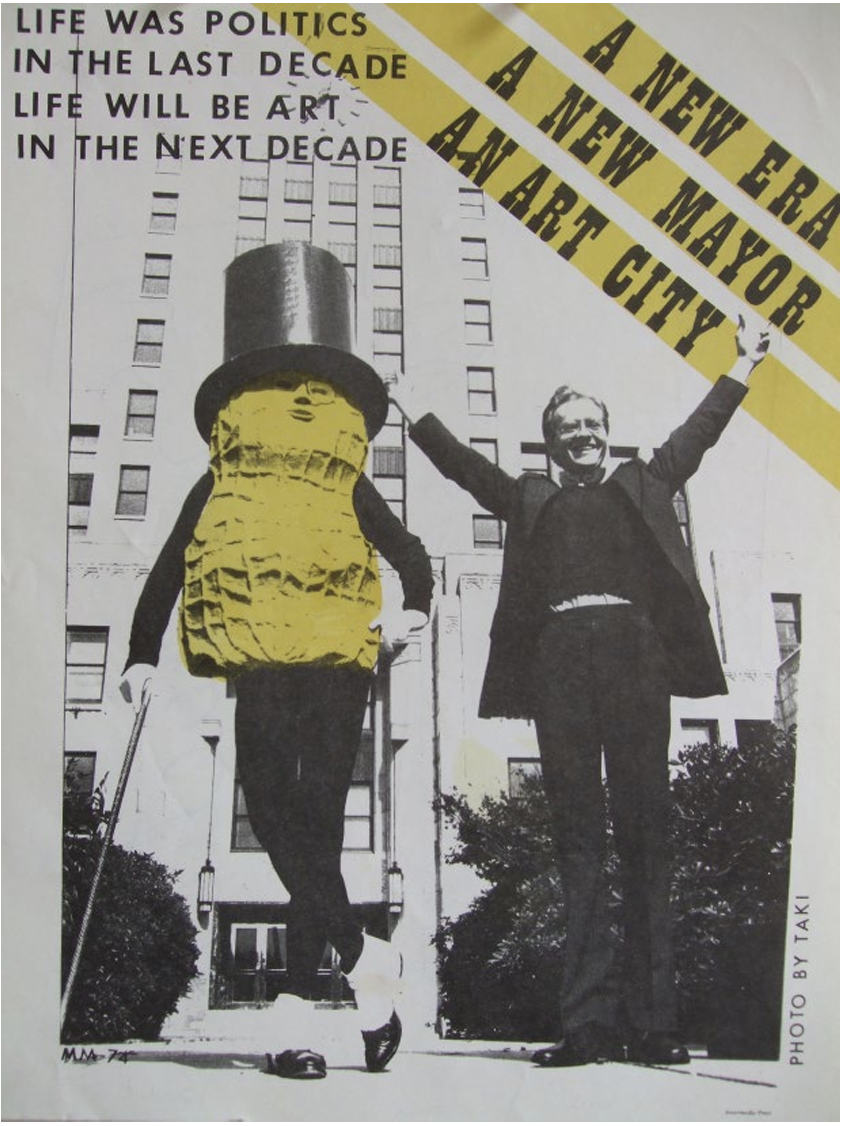

The seeds for the campaign were sown in 1969, when Mr. Peanut made his public debut in Halifax as part of a series of travelling Art City projects—performance art and photography showcases featuring the character in locations such as Los Angeles and New York. But it wasn’t until 1974 that Trasov and Mitchell decided to take the character in a new direction.

“It was John Mitchell’s idea,” Trasov says of his late friend. “He was a sculptor, and he considered sculpture as a form of social animation. He wanted to run me not just as a candidate but as a work of art and a performance.”

Mr. Peanut first made local news on October 26, after being denied entry to the Queen Elizabeth Theatre for refusing to remove his costume. Mitchell seized the opportunity, announcing Mr. Peanut’s intention to run for office and telling Vancouver Sun reporters that being barred from entry was “a matter of justice.” From there, local columnists—faced with a paucity of headline-grabbing issues—turned the candidate into a sensation.

“I shall vote for Mr. Peanut because I feel it is my duty to vote,” James Barber wrote in a November 14 column in The Province, “and there is no way I can consider any of the other candidates as acceptable.”

“Actually, I sort of like the idea of Mr. Peanut as mayor,” Alan Fotheringham agreed in the Sun. “The enclosing of plastic within a human form, as in the incumbent, has now reached such a state of public relations perfection that the Politician as Artist is more understandable. Mr. Peanut, the Artist as Politician, is just trying to reverse the process.”

Some, including the NDP’s Brian Campbell and NPA candidate George Puil, didn’t share their enthusiasm. “Mr. Peanut has made a travesty of art,” Campbell complained to the Sun. “The artists of this city are hanging their heads in shame.”

The abrasive Puil took it one step further, accusing Trasov at an all-candidates meeting of making a “mockery” of democracy itself (Mitchell issued a rebuttal days later, quipping that, given the state of democracy, such a thing was “impossible”).

“Fortunately, we didn’t have to prod them to make fools of themselves,” Trasov says, chuckling. “They did that on their own…. They screamed and ranted, and I guess that was their performance.”

Throughout, Mr. Peanut appeared at events across the city, sitting onstage with the other candidates but answering any policy questions directed to him with his signature 20-second tap dance.

Mr. Peanut campaign artwork.

“[It] brought the most enthusiastic response of all from the crowd of about 150 students in the student union building,” the Sun reported of a November 9 campaign event at UBC. “The other candidates, with slightly less animation, did their things.”

Then, as election day approached, something unexpected happened: the Peanut Party began to be taken seriously.

“It is the gravest hour in human history,” journalist (and Greenpeace co-founder) Bob Hunter wrote. “Yet, when I look to the theatre of political action, to see what is happening to deal with the nightmare that is rapidly enveloping us, I see no practical steps being taken at all…. Not one has had the courage to stand up and say ‘Look, folks, we face a rather desperate situation, and it’s time we did something realistic about it.’ Mr. Peanut says they are all nuts. I agree completely.”

“The size of the Peanut vote will be important in a number of civic elections in North America,” The Province’s James Barber added, “because it will indicate the groundswell of resentment which ordinary people are feeling against manipulative politics which deny human rights.”

“Mr. Peanut and the Peanut Party hold a deep respect for the democratic system,” Mitchell wrote, in a November 18 Province article. “We are not entering the arena of politics to waste press time. Boring, repetitive rhetoric borrowed from mediocre political theoreticians is approaching the ideals of democracy on one’s hands and knees. By these standards, Mr. Peanut is the only serious candidate for the mayor’s chair.”

Despite these unexpected endorsements, Mr. Peanut ultimately came in fourth place, with 2,685 votes—approximately 3.4 per cent of the total. Undeterred, Trasov and the Peanettes crashed the election night victory party of Mayor Art Phillips, shaking hands and entertaining the crowd with the song “Peanuts from Heaven.”

“On quite a small budget we gained about $150,000 of publicity for all the candidates,” a jubilant Mitchell told The Province. “Maybe in the next campaign Phillips will be back with the Tijuana Brass and dancing girls, Puil with something else, and Campbell with bongo drums.”

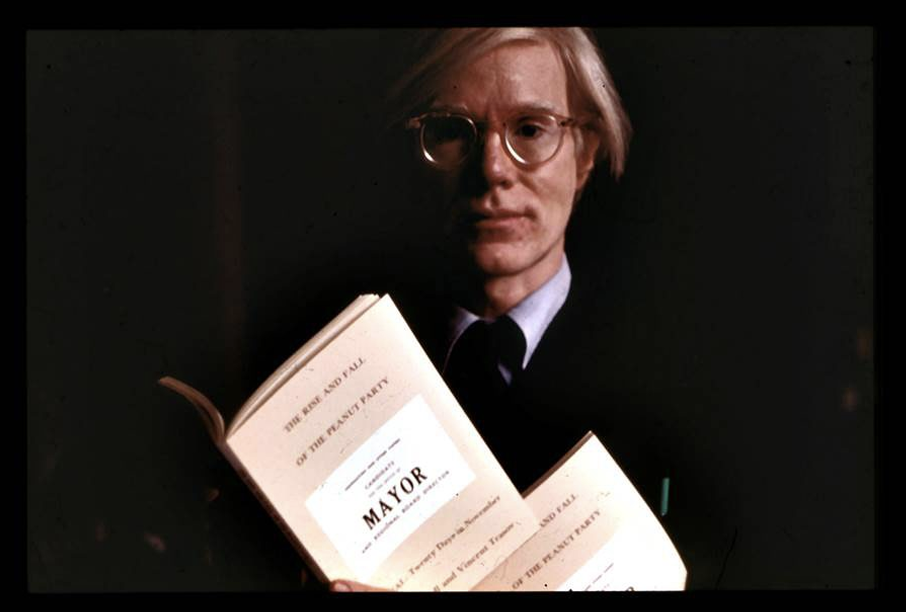

The campaign continued to resonate for several years afterward. In 1975, Trasov and Mitchell published The Rise and Fall of the Peanut Party, a book detailing their experiences. The same year, they were invited to speak in New York, in front of Andy Warhol. Back in Vancouver, however, the reception was less rosy.

Andy Warhol with a copy of The Rise and Fall of the Peanut Party.

“After the campaign, the Western Front got blacklisted,” Trasov says. “We couldn’t get funding from the city for a long time.”

Nonetheless, the legacy of the Peanut Party, and the artists who created it, lives on. The Western Front Society remains one of the city’s preeminent artistic nonprofit organizations and has served as a guide for other such societies across Canada. Today, Trasov’s association with Mr. Peanut continues. His 2020 debut show in Berlin was intended to introduce European audiences to the character and featured drawings, sculpture, and archival materials. At 78, his artistic ambitions remain broad—he works in a variety of disciplines, from drawing to chainsaw carving, and is set to open a new show at his gallery, Chertluedde, in January 2025. He’s also hard at work establishing an artist-in-residence program near his home in Brandenstein, Germany. But no matter what, he inevitably returns to the character who took Vancouver’s political world by storm 50 years ago, and who he feels may still have more to say.

“I think it’s more important now than ever,” he says. “At some point, I’ll get tired of working on my other projects and get back to Mr. Peanut. He’s a lifelong friend.”

Read more stories about Vancouver history.