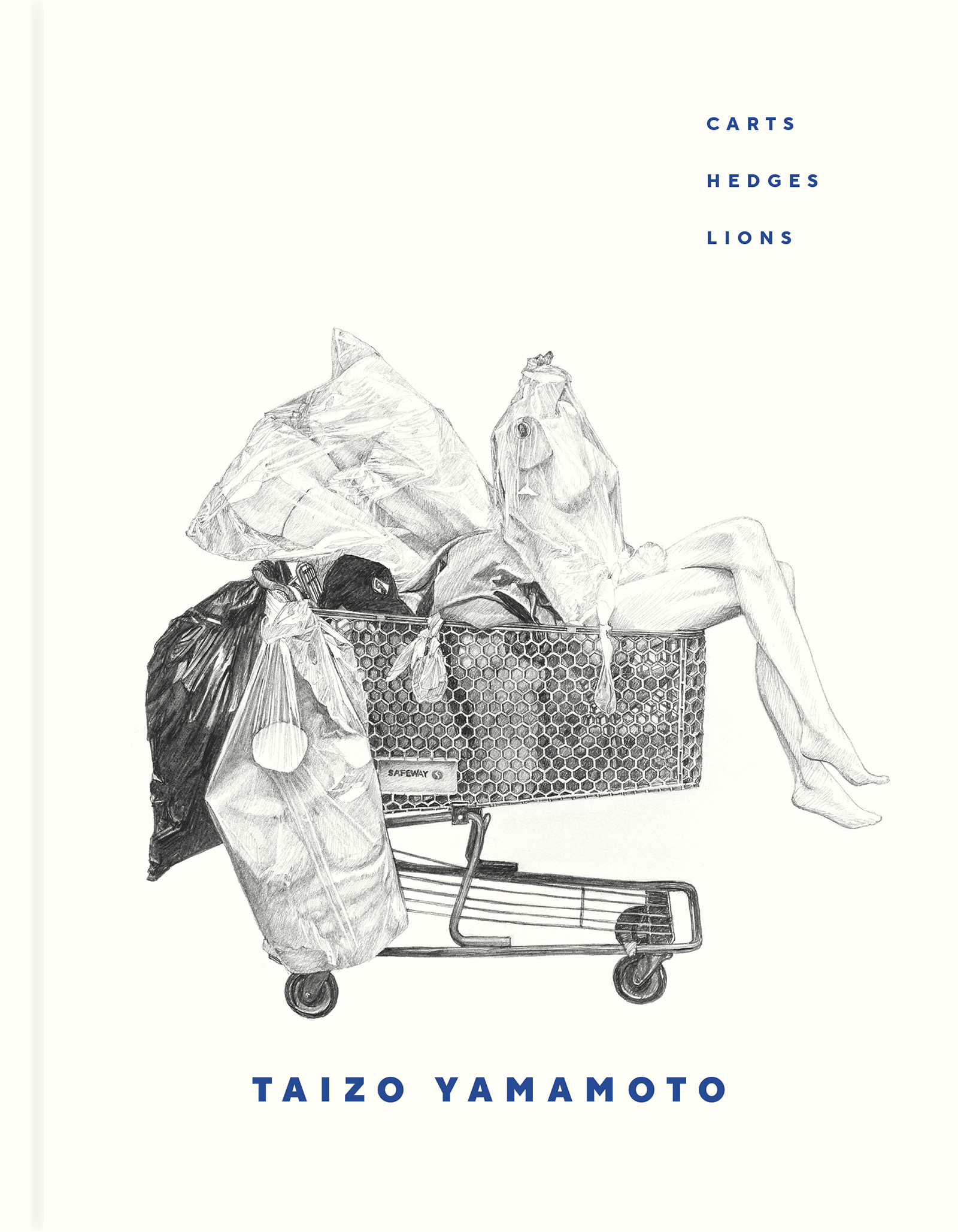

In Carts, Hedges, Lions, Vancouver architect Taizo Yamamoto documents real-world examples of assembled, grown, and built objects common to distinct milieus of Vancouver in three series of intricate graphite drawings. These excerpted images are part of the first series, focused on shopping carts. Republished in full is the accompanying essay “Evident Belonging” by author Aaron Peck.

For years, on Avenue des Gobelins in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, a man sheltered under the awning of an abandoned commercial storefront. He built himself a small structure using old beds as walls and a blanket as a door. On the mattress facing the street, he scrawled the phrase, “LE VIEL HOMME ET LA MER,” a misspelled French translation of the title of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. I used to walk by his home and wonder what it was about the novel that inspired him. I recently found myself in that part of the French capital again. The elaborate nest is gone, including the graffitied wall-bed, though the man still stays nearby.

In his shopping cart drawings, Taizo Yamamoto depicts traces of similar mysteries in Vancouver. Known for his work with Yamamoto Architecture, the artist here produces a body of work that appears to supplement his day job, with images that seem to parallel the design and production of buildings. He treats the carts the way an architect might: their users, who are also the owners of their contents, are unidentified and absent, similar to how architectural drawings render the structure, not the inhabitant. And yet, however connected his work as an architect may be to his output as an artist, these pieces are independent and involve different concerns.

From 2005 to 2008, Yamamoto took walks around Vancouver, particularly in the downtown core, during which he noticed the many shopping carts of unhoused people. “I would walk through the city,” he told me via email, “and be ready to photograph any carts that stood out as being particularly intricate or unique.” He was careful to take snapshots while the carts were unattended or when their stewards were otherwise preoccupied. Back in his studio, the artist made drawings from the photos. This series, which renders these repurposed vernacular structures, then focuses on the particular gatherings of objects collected in them. All cropped the same way, the compositions are uniform, consisting of the carts only in side profile, each pencil-drawn in the same method. In some, select details are coloured, such as the blue plastic of a Toys “R” Us cart and the pink floral print of an umbrella, although the majority remain uncoloured, leaving them with a forensic quality.

Shopping Cart #1.

At first glance, his work acts as a document of the ubiquitous yet often ignored form of ephemeral architecture found across Vancouver’s urban landscape. But these pieces also present a nuanced appreciation of the shopping carts, especially in our era of economic disparity. Yamamoto’s drawings attempt to address the contradictions in how we encounter these objects by providing his subjects a certain respect. These carts are, no doubt, a phenomenon that requires discretion to observe, because looking directly at the personal effects and shelter of an unhoused person breaches a tacit social contract. We avoid gawking at the interior domestic spaces of strangers, except the rich and famous, so it follows that we should afford those who find shelter in public spaces the same respect. This means these structures are often avoided, even underappreciated. The drawings then give us the ability to reflect on the nuanced aesthetic appreciation of these objects. It feels particularly poignant during the current housing crisis, which finds large numbers of individuals without safe places to live. These works can give us pause to look at what we might turn our eyes away from in public. Yamamoto’s use of colour further mimics how we look at the items contained within the carts. The rare pops of pink or blue produce an effect similar to those brief moments in real life when a detail in a cart catches our eye before our gaze shifts toward a neutral object of attention. More than a record, the drawings represent how we see these things.

The series’ documentary quality, not to mention meticulous realism, calls to mind certain photographic artworks. Formal and thematic similarities exist with Walker Evans’s Beauties of the Common Tool, a 1955 series in which the celebrated photographer presents his subjects in a direct and simple way, as well as the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose studies of German factory buildings from the early 1960s onward provide the viewer with typologies of industrial architecture. A local reference emerges in the drawings’ affinity to Stephen Waddell’s Man in Green Mask (2009), a photograph of a man wearing a bright-green Halloween mask pushing a blue plastic shopping cart in what appears to be the Downtown Eastside. Even if the two art forms are in dialogue here, they have different functions: one is the source, while the other is the result.

Shopping Cart #3.

Shopping Cart #10.

As he walked around Vancouver, Yamamoto selected carts to photograph, ones he found visually interesting. But what details make something “particularly intricate or unique,” to use his words? The drawings, in this case, provide the clues. They are the items that hint at the complex inner lives of their owners. One cart is full of mannequins; another, stuffed with suitcases. A spare bicycle tire rests on the bottom rack of another, while a hockey stick protrudes from its plastic-covered contents. Umbrellas abound. A carry-on bag hangs over the handle of another. One is so encumbered with garbage bags that the cart is no longer visible. One is almost entirely empty, except for a pile of empty cans, perhaps not even used to house personal effects. Each one hints at a story, the plot of which remains unknown to us.

Back on Avenue des Gobelins, I often considered asking that man about his choice of words for the mattress barrier, but I always opted against it. In any case, something about Yamamoto’s shopping carts reminds me of that shelter and its cryptic literary reference. They are evidence of private stories in plain view. Informed by both his training as an architect and photographic traditions, these drawings represent their subjects, in a time of widening inequality, with a certain curiosity and carefulness by keeping their mysteries unsolved.

Shopping Cart #11.

Shopping Cart #13.

Shopping Cart #17.

Excerpted from Taizo Yamamoto: Carts, Hedges, Lions by Taizo Yamamoto. Copyright © 2024 Taizo Yamamoto. Essay by Aaron Peck. Excerpted with permission from Figure 1 Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Read more arts stories.