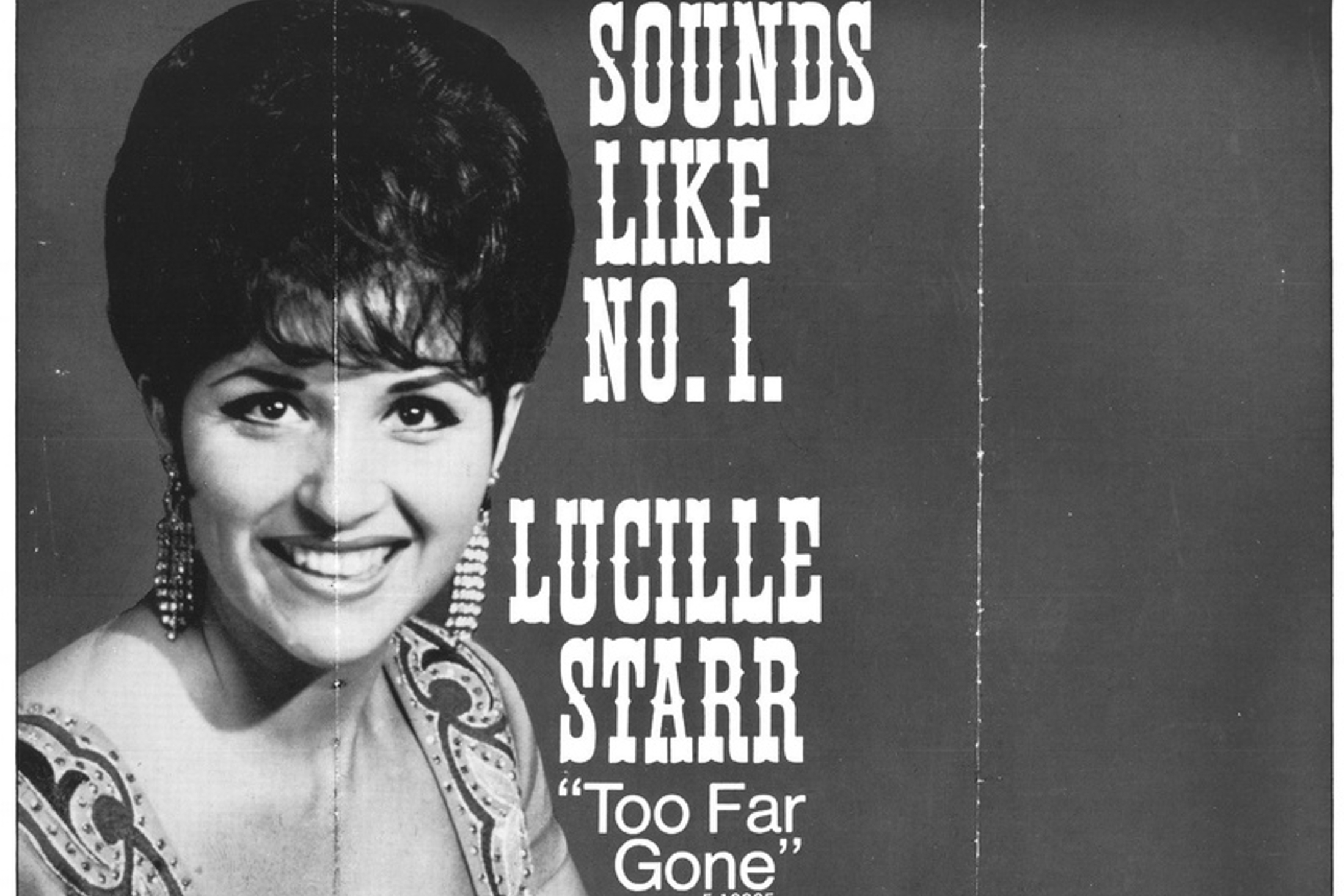

On radios around the world in that whimsical pop music year of 1964, one song sounded like no other.

It opened with a sad, slow horn. After a few beats, a crystalline voice joined in. “Quand le sol-eil-eil-eil dit bonjour…” The third word was trilled, extending the syllable. And, most surprisingly, it was in French.

“Quand le sol-eil-eil-eil dit bonjour aux montagnes et que la nuit rencontre le jour,” Lucille Starr sang in a down-tempo country warble. “Je suis seule avec mes rêves sur la montagne.”

Partway through, the song reverted to English: “When the sun says good day to the mountains, and the night says hello to the dawn, I’m alone with my dreams on the hilltop.”

The ballad about a lost love—dead or unrequited is left to the imagination—climbed the Billboard charts. It got as high as No. 54 on the Hot 100 in the United States, reached No. 12 in Canada, and, in cities such as Ottawa, the song rose past one-hit wonders like “Hippy Hippy Shake” and Louis Armstrong’s ubiquitous “Hello, Dolly!” before ascending beyond even the Beatles and their fellow British Invasion mop toppers to reach No. 1.

The bilingual song became a hit on four continents. The singer toured the globe to perform a tune titled “The French Song” because the owner of her record company could neither remember nor pronounce the foreign words of the title.

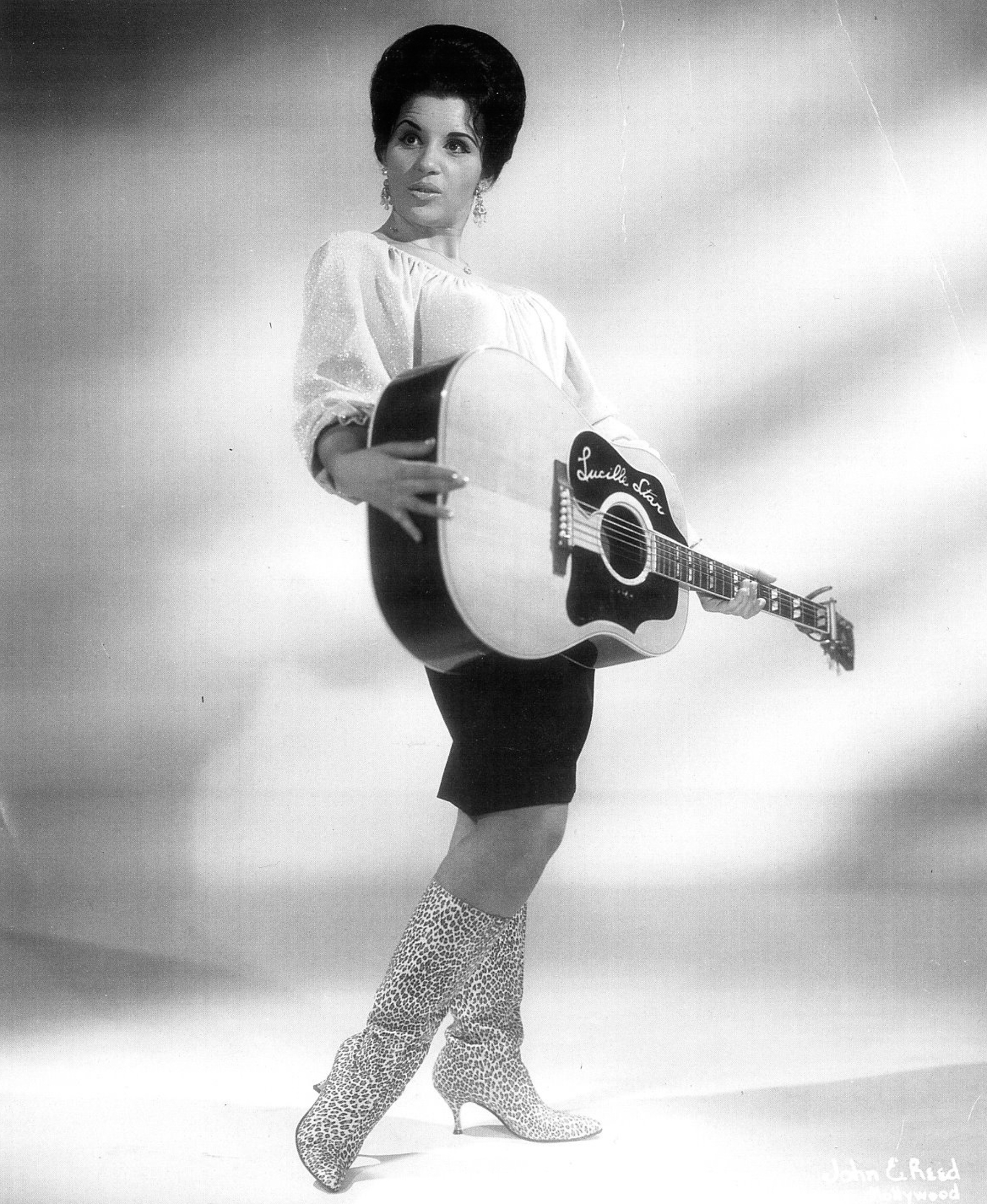

A petite figure with towering, country-style hair, whose stage wardrobe often highlighted an impressive décolletage, Starr became an overnight sensation after a long decade of playing small halls and smoky clubs, country fairs, and country bars.

In her hometown, Starr’s great achievement went mostly unnoticed.

Photo by John E Reed, courtesy of the Manitoba Music Museum.

She grew up in a house at 211 Begin Street in the francophone community of Maillardville in the Vancouver suburb of Coquitlam. She had been born in St. Boniface, Manitoba, the only child of Aurore and Gerard Savoie, a fiddler and former cobbler who found work as a labourer and millwright at a mill on the Fraser River. Lucille attended Our Lady of Lourdes school at the top of Laval Street, a 10-minute walk north, where the family’s language, faith, and culture were shared and protected for another generation.

On Sundays, the Savoies attended the nearby Roman Catholic church of the same name, a simple, whitewashed wooden building with a steeple visible throughout the community.

The girl’s singing attracted attention even before she attended school, as an uncle liked to pay her pennies to sing bawdy songs with risqué lyrics. (Her mother put a stop to that.) At Maillardville weddings and social events, she performed with an all-girl group called Les Hirondelles (The Swallows). One day, she boldly talked her way onto the radio to perform with Jackie Jensen’s Rhythm Pals, a male trio who had toured the province with Wilf Carter.

As a teenager, she joined the Keray Regan Band, crooning the bandleader’s “My Home by the Fraser,” a 1948 hit. (Regan, who was born Oscar Melvin Frederickson in Pouce Coupe in British Columbia’s Peace River region, changed his name after becoming a Kabalarian.)

While with the band, she began a romance with the bandleader’s young brother, Bob. The couple married in 1956. A wonderful singer and talented guitarist, she took as her stage name Lucille Star, later changing the spelling to Starr. The couple performed as Bob & Lucille and then called themselves the Canadian Sweethearts.

They settled in Los Angeles, playing clubs and releasing rockabilly, as well as pop and country singles, building a modest career that included appearances on television, notably on Cal’s Corral, a live country-and-western show sponsored by car dealer Cal Worthington.

In 1963, they were signed to A&M Records by Herb Alpert (the A in A&M). That same year, Starr performed as an uncredited yodeller for Cousin Pearl in the “Elly’s Animals” episode of the popular sitcom The Beverly Hillbillies.

Alpert saw great potential in Starr and her vibrato as a solo performer. He produced and handled the arrangements for “The French Song” on which his Tijuana Brass band played, confident that this odd hybrid of a song would be a sure-fire hit. It sold more than seven million copies worldwide, making Starr the first Canadian woman to earn a gold record (100,000 sales) and the first to sell a million records. She also won a prestigious Golden Tulip Award from the Dutch recording industry.

The record’s success did not ease tensions in a troubled marriage with a domineering and now overshadowed husband. The Canadian Sweethearts were anything but. They continued to perform together until the mid-1970s, appearing on such television programs as Hee Haw and The Ronnie Prophet Show. Their union, which she once described as a “living hell,” ended in divorce.

“It was like a tornado every evening, every day, every morning,” she told the Tennessean newspaper in 1987 after moving to Nashville.

A happy second marriage led to a revived solo career. She found an audience for country singles (“Power in Your Love” and “The First Time I’ve Ever Been in Love”) and albums (The Sun Shines Again, Back to You, Sweet Memories, and Chansons d’Amour/Songs of Love). Her older work was re-released and appreciated anew. Overdue accolades began to roll in. She was the first woman to be inducted into the Canadian Country Music Association Hall of Fame, and she was made an honorary inductee of the Manitoba Aboriginal Music Hall of Fame. Her life story was the inspiration for the stage play Back to You: The Life and Music of Lucille Starr.

In 1988, she returned home for a two-day festival put on by volunteers in her parish to honour a local who made good and not only continued to speak French but sang it for the world’s enjoyment. A highlight of the homecoming was the naming of a street after her. Lucille Starr Way runs north of the Lougheed Highway through an area of malls and industry.

Lucille Marie Raymonde Savoie, known to the world as Lucille Starr, died in Las Vegas in September. She was 82.

Read more stories of Hidden Vancouver.