In 1660, the artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) was forced to sell his house and printing press in order to satisfy his creditors. Never particularly good with money, Rembrandt had built a very successful career, supplementing his income earned from his many religious and portrait paintings with the profits from the sale of his etchings, which number around 300. While not expensive when sold individually, Rembrandt could produce about 1,000 impressions from a single plate, which, when eagerly collected by the buying public, would build his international fame as well as his fortune. After his press was sold, Rembrandt never produced another print. Two of his prints, a self-portrait executed in 1638, when the artist was at the height of his career, and a second print, showing the head of his beloved first wife, Saskia, currently hang next to each other on the walls of the Burnaby Art Gallery, as part of two temporary exhibits, running until November 17.

These two exhibits, Storms and Bright Skies: Three Centuries of Dutch Landscapes and Inner Realms: Dutch Portraits, feature works on paper from the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria respectively. As the third largest public art collection in B.C., and the only museum in the country with a dedicated collection of works on paper, the Burnaby Art Gallery is well set up to transport visitors to the land of windmills and canals.

Among the works on display are a number of remarkable pen and ink and charcoal drawings of real and imagined landscapes, including Jan Brueghel the Elder’s Mountain Landscape. Brueghel’s distant mountains are painted with a blue wash, recalling Leonardo da Vinci’s advice that mountains seen from far away appear to the eye not white or brown, but blue, and thus should be painted so.

Two black chalk drawings by Simon de Vlieger were probably studies made for a much larger painting project. Vlieger likely used chalk, instead of pen and ink, in order to capture the trees while sitting outside, a practical decision given how unwieldy an ink pot might be as one sits in the middle of a field or forest. Vlieger would have taken his chalk drawings back to his studio where he could incorporate them into a larger composition.

Many of the landscapes recall the Renaissance Italian way of depicting rural scenery and it is important to recognize that many of these Dutch artists became familiar with this style not necessarily through travel to Italy, but by collecting prints by Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo and later, Annibale Caracci. Part of a series of landscapes, the Herman Naiwincx etching called The Cascade illustrates the way in which Dutch artists were influenced by these Italian models, with its rushing river and idealized hamlet on the hill behind.

Prints and drawings such as these encourage, and in some cases, require, close looking. In the Renaissance, etching was considered a painter’s art, given that the technique is basically drawing in wax onto a metal plate. When dipped in acid, the lines that the artist has made in the wax allow the acid to eat away at the metal, while the areas still covered in wax are protected from the acid. Unlike engraving, where an artist has to carve into the metal plate, etching requires little specialist knowledge and would allow a painter to work in much the same way they might with pen and paper. However, the ability to reproduce a print, rather than a drawing or painting, enabled the artist to build their reputation and their bank balance.

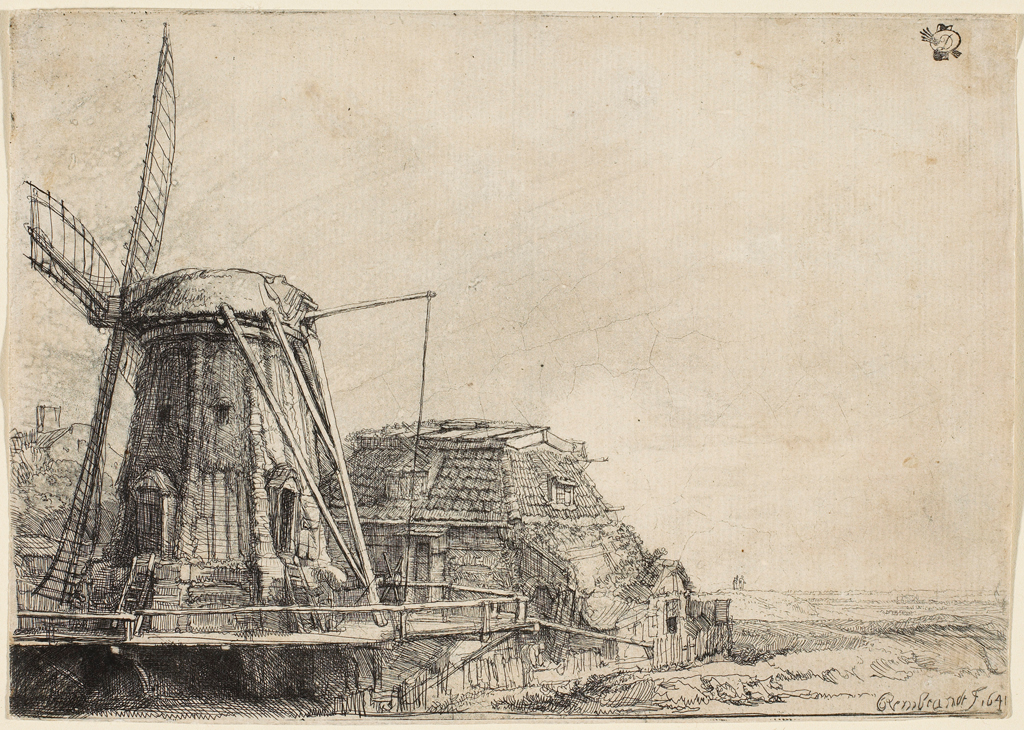

For centuries, collectors have amassed the work of these artists, binding them in albums in order to protect them from damage and wear. Works on paper should only be displayed for three months at a time, and while these works are treated with great care now, previous generations of collectors thought nothing of marking the prints and drawings that they owned with personalized marks. In the exhibit, Rembrandt’s beautiful etching, The Windmill, sports a small collector’s mark in the upper right hand corner, allowing us, hypothetically, to track the print’s previous owner.

In Rembrandt’s case, a signature was not always necessary, but for lesser-known artists, it was essential that they sign their print. Ludolf Backhuysen did just this in his two etchings, Seascape with an Anchored Ship and Ship on a Rough Sea, both from 1701, signing in tiny Latin print, “L Backhuisen Fec[it] et exc:[udit] cum Privil[egem]: ordin: Holland: et West Frisiae,” meaning L. Backhuisen made and printed this, with the privilege of Holland and West Frisia. This signature allowed Backhuysen not only to claim authorship, but also to celebrate the monopoly he had on this print, protecting his work from counterfeiters. In order to see Backhuysen’s signature and many other tiny details in these two exhibits, bring your magnifying glass to the Burnaby Art Gallery and prepare to be amazed.