Elizabeth Zvonar has already made a collage of sorts. The artist’s table, in her temporary studio at Burrard Arts Foundation (BAF), is meticulously covered with clippings from magazines, a stack of them piled up next to her chair. “I’m not sure yet if any of this is going to make it into the cut,” she says, in reference to her upcoming show “To you it was fast” (April 6 to May 20) at BAF as part of the 2017 Capture Photography Festival.

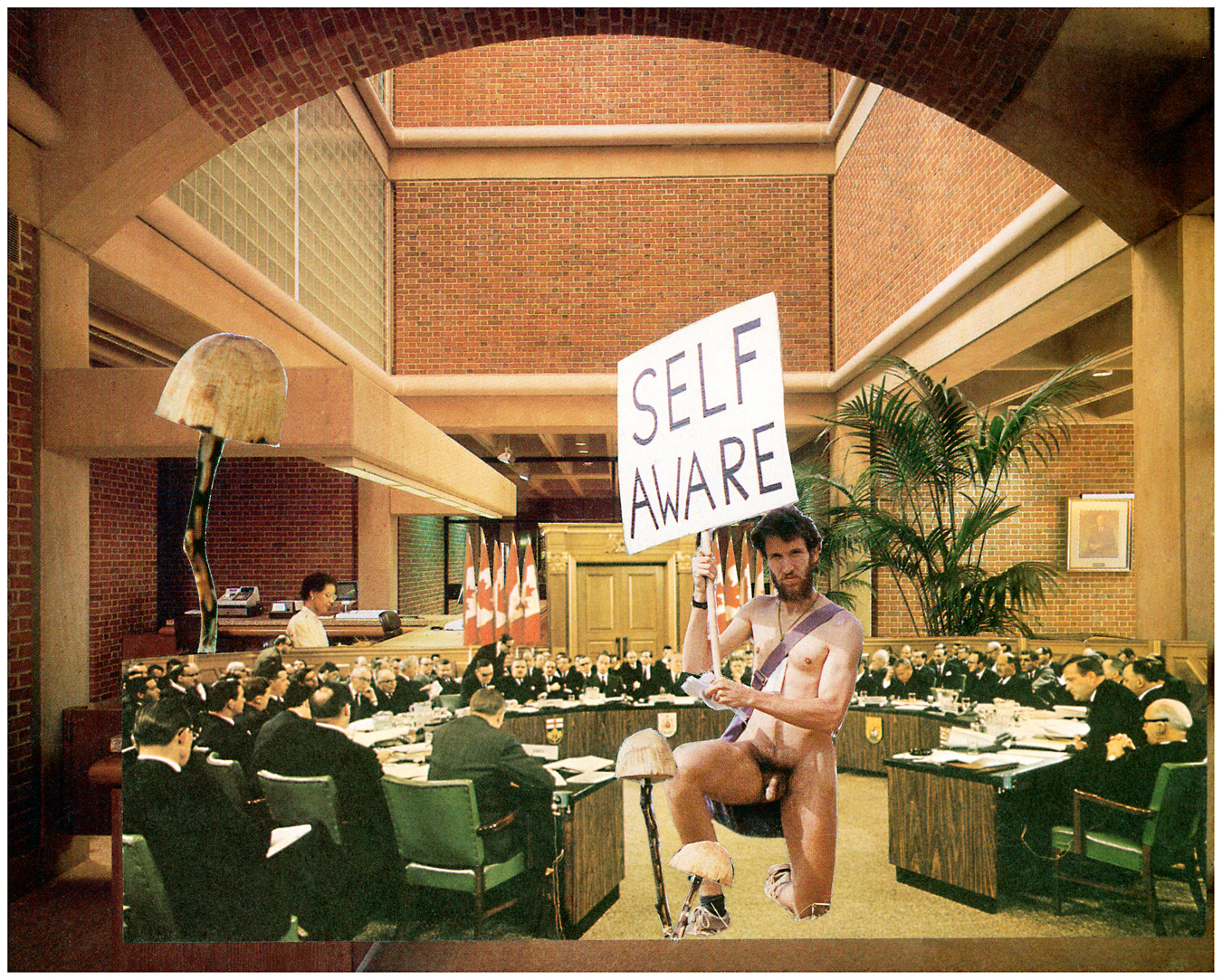

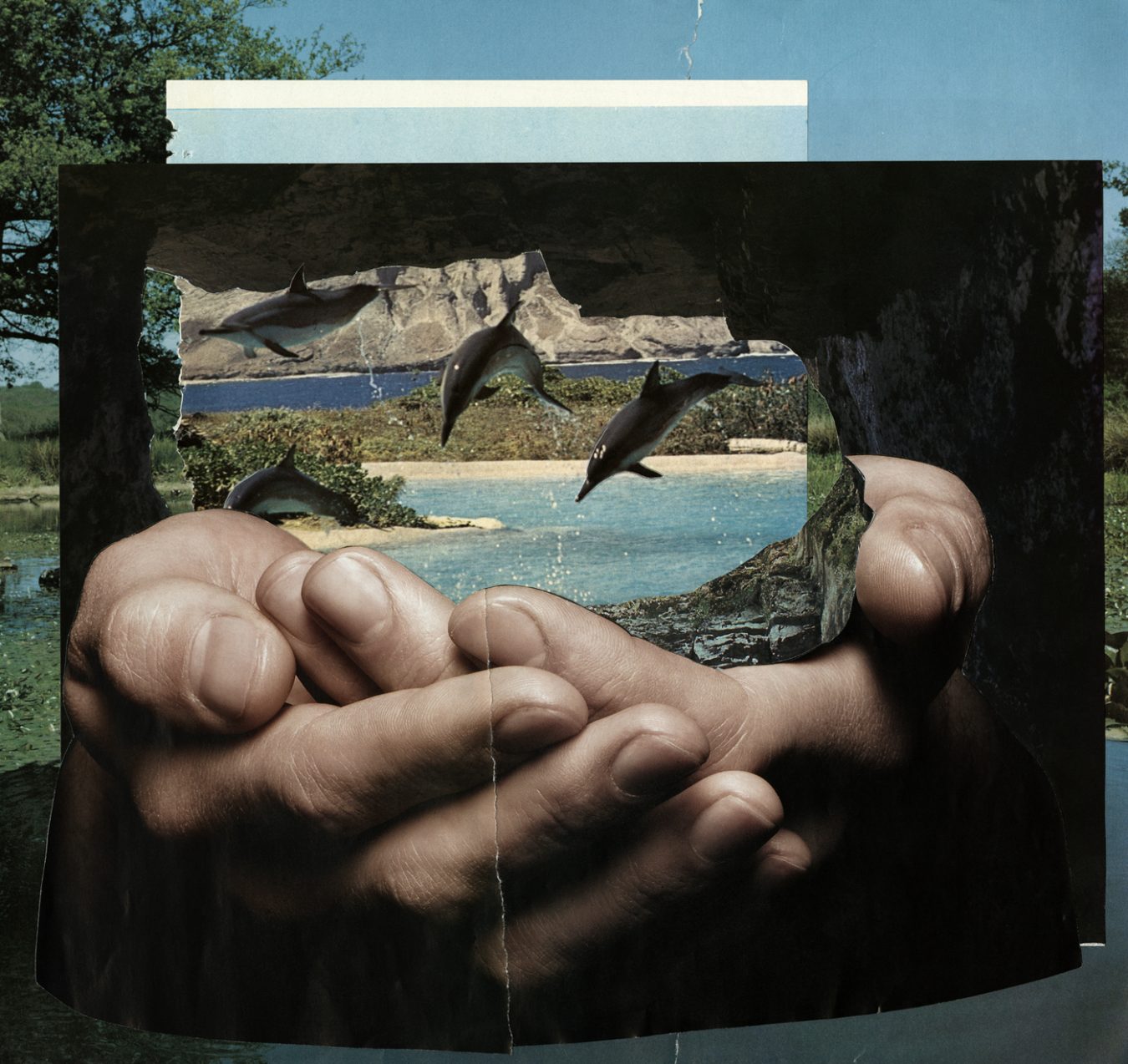

Her ambiguity makes sense; a large part of her practise relies on the editing process. For Zvonar, whose previous solo exhibitions have shown at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Daniel Faria Gallery, Artspeak, and the Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite, the challenge of collage is displacing the images. Her work, made up of found materials largely from glossy fashion publications, is centered on a reductive method, obscuring and obfuscating images encountered every day. “Less is more, for sure,” she says. “I’m looking to create a space where, as a viewer, you can find something in it. It’s always going to be a subjective experience.” The found images—collected photos from lifestyle, art history, advertising—are reproduced to present an alternative message, an alternative history.

The female body is Zvnoar’s most studied subject. Using clippings from magazines, as well as sculptures of appendages (often her own), Zvonar takes away the original, often sexualized meanings, and works to re-appropriate the body. “I’m interested in the push-pull of the ugly and beautiful, the grotesque and the beautiful,” she explains. “I’m interested in pushing aesthetics to the point where it is uncomfortable.” Examples of this show up frequently in her work, particularly in her sculptures. The Spectre, The Serpent, The Ghost, The Thing, a work from Zvonar’s 2013 show at Daniel Faria, is held up by gold-plated bronze stilettos that are clamped directly (almost painfully) to the piece. The collage image, of a blonde showing lot of skin, appears to be pinned down by these instruments.

Context, in our visual culture, means everything.

“I think we’re inundated with a visual lexicon,” says Vancouver-based Zvonar, who was a runner-up for the international AIMIA AGO Photography Prize in 2016. “When we go out on the street there are all of these visual images, so I want to make something that stops someone in their tracks to take a double look—that movement when someone has to think for a moment, that moment when someone is confused.” Zvonar’s work can often be confusing, at least at casual glance. To a contemporary viewer, a woman’s nude body may seem more comfortable when used to help sell perfume than when Zvonar removes it from that promotional context. “I’m looking at bodies in a different way than the way that they’re commodified in fashion and advertising,” she says. “I find myself often using advertising content and trying to obscure the objective.” Context, in our visual culture, means everything.

Zvonar does leave clues for understanding her work—each piece’s title offers didactic insight into her coded imagery. “I can make an image, and then the task is to come up with a title for it, and that can take months and months and months,” she says. The name often reveals a bit about the work’s lineage. An orifice-like readymade sculpture, Marcel Meets Judy, for example, perhaps refers to Marcel Duchamp and Judy Chicago. Titles, in Zvnoar’s eyes, are an important element of female-made art, acknowledging history within craft and person. “Untitled—that feels like a cop-out,” she says. “I believe in biography in work, I think that’s an interesting aspect of an artistic practise. To deny biography, it’s patriarchal.” There’s a choice here, to use Zvonar’s titles as ways into the works, or to find something within one’s own reading—but the important notion is that there are options. Nothing in Zvnoar’s work is oppressive; agency is king.

Keep up with our Arts section.