In their new book Where the Power Is: Indigenous Perspectives on Northwest Coast Art, UBC Museum of Anthropology curators Karen Duffek and Bill McLennan, along with Musqueam First Nation guest curator Jordan Wilson, ask 81 Indigenous artists, activists, thinkers and knowledge-holders from the Pacific Northwest to reflect on cultural objects held in the museum.

What does it mean when objects created a century or more ago are returned to this part of the world, still institutionally held but newly accessible to Indigenous communities? What power may the objects carry for those who are seeing and holding them today—perhaps for the first time? In this excerpt, a centuries-old Tlingit dagger prompts reflection on the differences between a tool and an artifact, and between the institutional power of museums and the ancestral knowledge of communities.

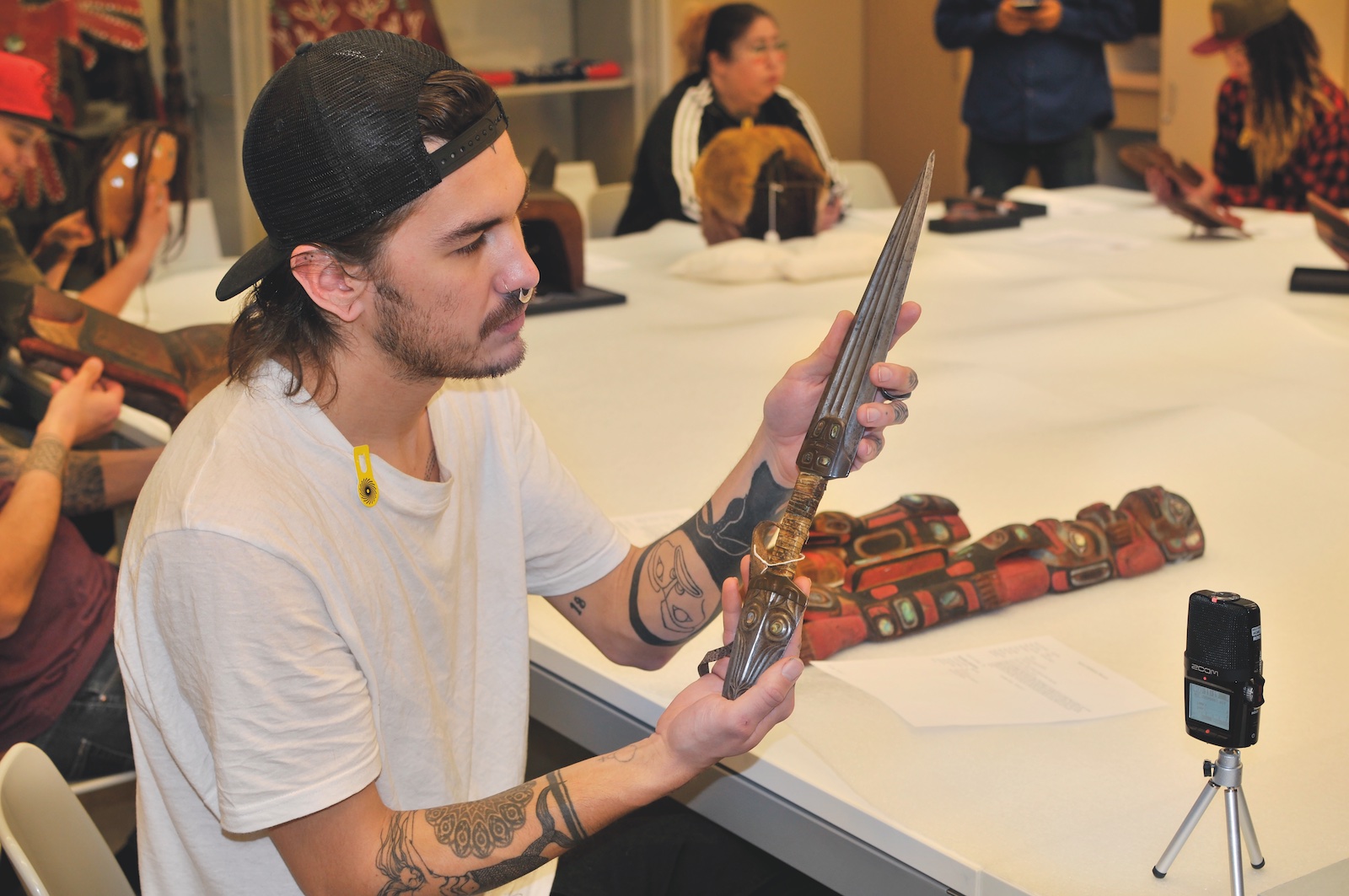

The objects are neatly laid out on the long laboratory table and bathed in fluorescent light. Some have been removed by museum staff from their usual spots in the display cases, replaced by small placeholder cards assuring visitors that their absence is only temporary. Other objects have been wheeled into the lab on carts from the museumʼs behind-the-scenes storage room. A few of the pieces are here at the Museum of Anthropology (MOA) on loan from other institutions or private collections. As curators, we have invited Ts̱ēmā Igharas, a young Tahltan artist, to come in for an afternoon of hands-on study of these historical Indigenous belongings from the Northwest Coast of North America.

She lingers over each piece, picking it up, methodically turning it over in her hands, sharing her thoughts on its making, its origins, its potential. “These artifacts, because they still exist, are a benchmark for our contemporary makers,” Ts̱ēmā reflects. “Itʼs accessing and circulating these pieces thatʼs often the barrier. I mean, can you imagine if everybody got to hold this dagger?”

In the two centuries or more since a Tlingit metalsmith created that dagger, it has passed through many hands. Its maker and first owners are now unknown, and perhaps it was transferred to others within and beyond Tlingit territory through inheritance or warfare, or as a commission or gift. The oral histories and clan relationships it came to represent in those early journeys did not accompany this object, however, as it was eventually sold, traded, or taken outside those communities and entered the market for ethnographic curios and art. Circulating in that global realm of collectibles, the dagger transformed as both symbol and functional tool. Indeed, the activation of purpose inferred by its Tlingit names—gwálaa (“something with which to strike”) or jix̱án át (“thing close to hand”)— were overlaid by the daggerʼs new repose as an “artifact”: a thing to be admired for its aesthetics and form, the disembodied creation of a distant Other. As such, it travelled widely, through successive collections, its final sale occurring in 2014 at a Paris auction. Three years later, the dagger, valued for its rarity and age, was among over four hundred historical and contemporary works of Northwest Coast art bequeathed to MOA by Elspeth McConnell, the late Montreal collector and philanthropist.

“I look at the complexity of the displacement, and locate it so that Iʼm not so daunted by not knowing— and by the task of trying to find out more. Now we have the immediacy of trying to still figure out what the form and function of each object was and is. Itʼs an emergency, right? Iʼm sure many people are curious and enthusiastic about just simply knowing. Itʼs about actually connecting these things to our social networks again—to people.”

—Skeena Reece (Tsʼmsyen/Gitxsan and Cree)

This gift marked McConnellʼs commitment to return these works to British Columbia. Although it remains far from its original northern home, the daggerʼs geographical relocation to Vancouver, and its move from the private to the public realm, also helped to re-centre it in the present. It is now accessible for the first time to current generations of Indigenous community members. No matter their Northwest Coast nation of origin, all who have since visited and studied this extraordinary belonging have been captivated by the experience of actually holding the sleek and powerful weapon: to feel its weight and the contours of its form, to look closely at its details, and to admire its workmanship. Some have imagined mastering the techniques to hand-forge daggers again—a way of reclaiming knowledge that transcends the physical object.

Indigenous artists and researchers working with historical collections in museums today are making it clear that they require a relationship with those ancestral materials—and, by implication, a new relationship with the institutions. They are responding to the reality, often unstated but critical to thinking about Northwest Coast art in museums, that works from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries only rarely remain in contemporary Indigenous communities. Although much new regalia is being made and used and new poles raised in ceremony, it has become normalized, even expected, that most historical Indigenous “artifacts” are held in museums and private collections, locally and around the world. Some works, like the dagger, travelled through global networks before settling closer to home; thousands of other objects are widely dispersed and, despite increasing digital accessibility, out of reach for many Indigenous community members. The monetary value of this art, escalating since the 1970s, extends the displacement, as auction and art dealer prices are usually beyond the budgets of museums and First Nations communities alike.

“When we have our robes, we say that our ancestors are with us. These blankets, theyʼre powerful because they went through a lot of ceremonies and a lot of dances, a lot of potlatches, a lot of history. Thatʼs whatʼs in this robe. All the old blankets and regalia have a memory of these things. Thatʼs where the power is—you feel it. You go to the museums and you open those drawers and you can feel it.”

—Dempsey Bob (Tahltan/Tlingit)

Museums are embedded in this matrix of markets and power. With foundational collections built over the preceding century, institutional prerogative often enables them to receive major donations from collector-patrons, and to borrow important works for exhibition from other institutional or private sources—a matrix to which a small number of Indigenous cultural centres are beginning to gain access. Such networks can be seen as emblematic of the ongoing “complexity of displacement” that Skeena Reece describes above. Yet many belongings, from woven ceremonial robes to masks and feast bowls, were made to function in relation to family and community; they embody cultural rights, values, histories, and ways of knowing.

No matter how far the material objects have travelled, each piece anchors intangible knowledge to real places of origin, and to real people both past and present. This knowledge persists in communities, despite the objectsʼ absence. When access to the collections—including hands-on study, computer-based research, reactivating regalia in community ceremony, long-term loans to cultural centres, and repatriation— becomes a priority shared and facilitated by museums and originating communities and supported by donors and lenders, there is greater opportunity for current generations to once again connect to these ancestral objects.

Excerpted from Where the Power Is: Indigenous Perspectives on Northwest Coast Artby Karen Duffek, Bill McLennan, and Jordan Wilson. Copyright © 2021 by Museum of Anthropology at UBC. Excerpted with permission from Figure 1 Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Find more book excerpts.