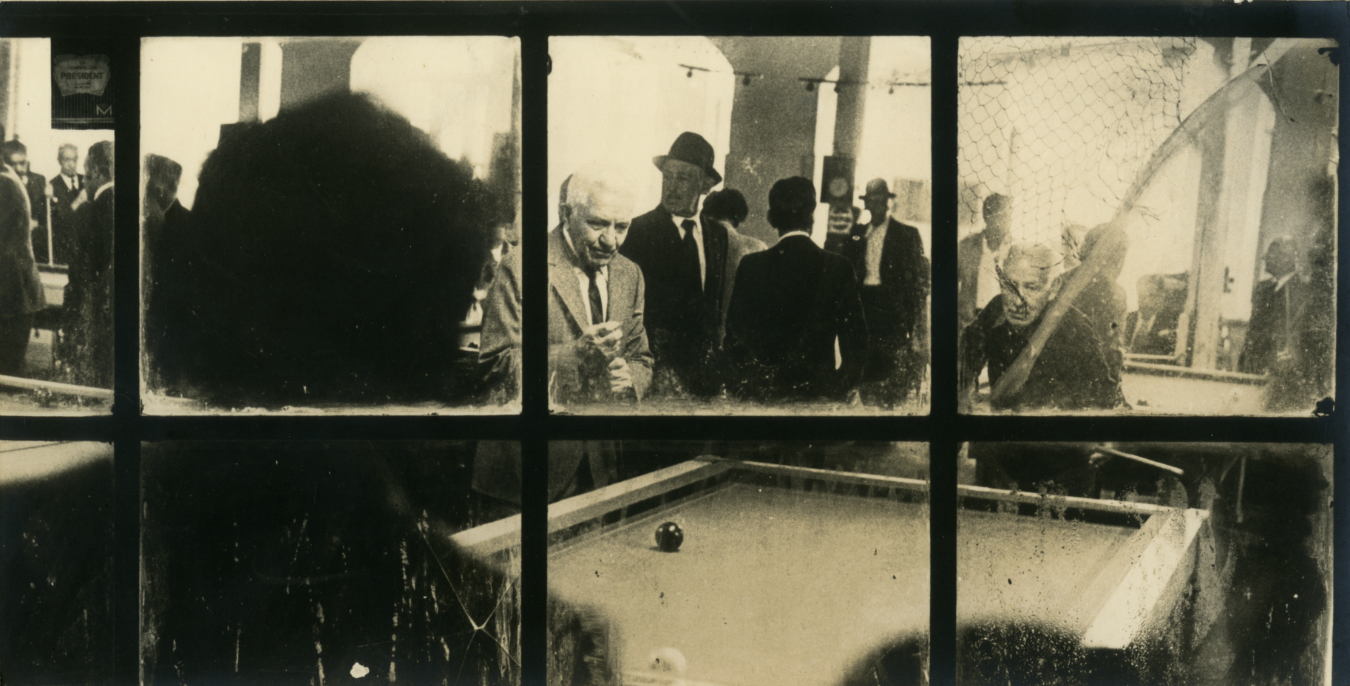

During his life, Fernell Franco didn’t receive international praise or fame. Working as a bicycle messenger, photojournalist, and photographer in his native Colombia, Franco was a vibrant figure in the arts community that developed out of Santiago de Cali, yet his name didn’t reach far beyond the borders of the country. Looking at the work on display now until June 5 at Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris, it’s impossible to not draw broader connections to international photographers of prominence. The artist’s repetitive, collaged images recall certain Andy Warhols; the links between painting and photography conjure associations to Ian Wallace, and his cinematic arrangements feel somehow Cindy Sherman-esque. It is certain Franco’s work fits with the history of photography, yet remains entirely distinct.

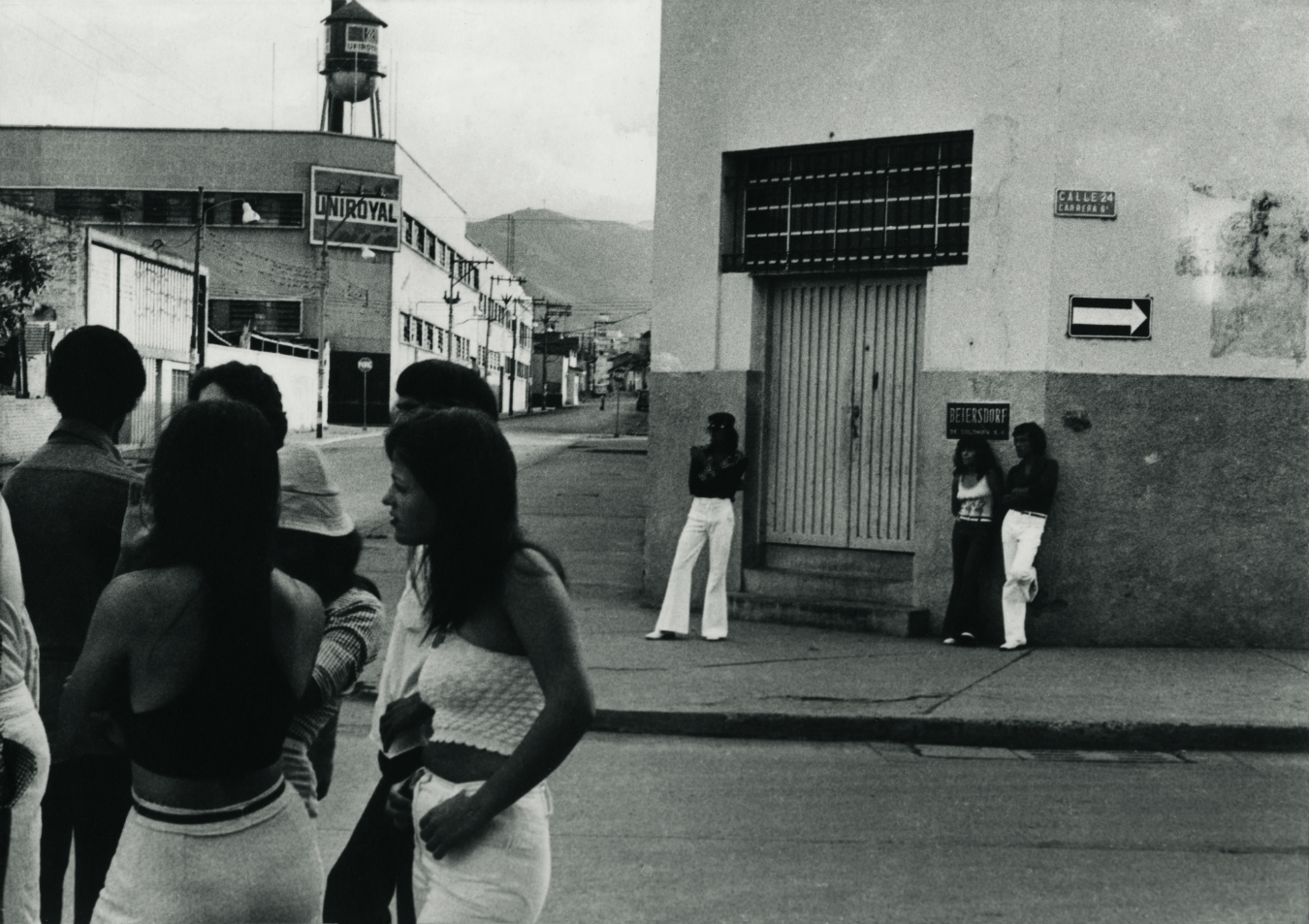

“Fernell Franco, I would say, is the most important figure in contemporary photography in Colombia,” says co-curator María Wills Londoño, who has been researching Franco for nine years, working closely with his family (he died in 2006). “He did a body of work, which is mostly unknown and internationally even more so. Unfortunately in Colombia, photography has not been taken seriously as a medium until really recently.” The work on display at Fondation Cartier, curated by Alexis Fabry alongside Londoño, comprises the artist’s first comprehensive retrospective in Europe and draws pieces beginning from 1970, when Franco first began working as a photographer. After moving from the countryside, as many others did, to flee bipartisan violence, Franco and his family settled in Santiago de Cali. “Fernell was not a single case: many people went to the cities because of the violence in the countryside,” Londoño says of the time. “So Cali went through a period of growth that was uncontrolled.”

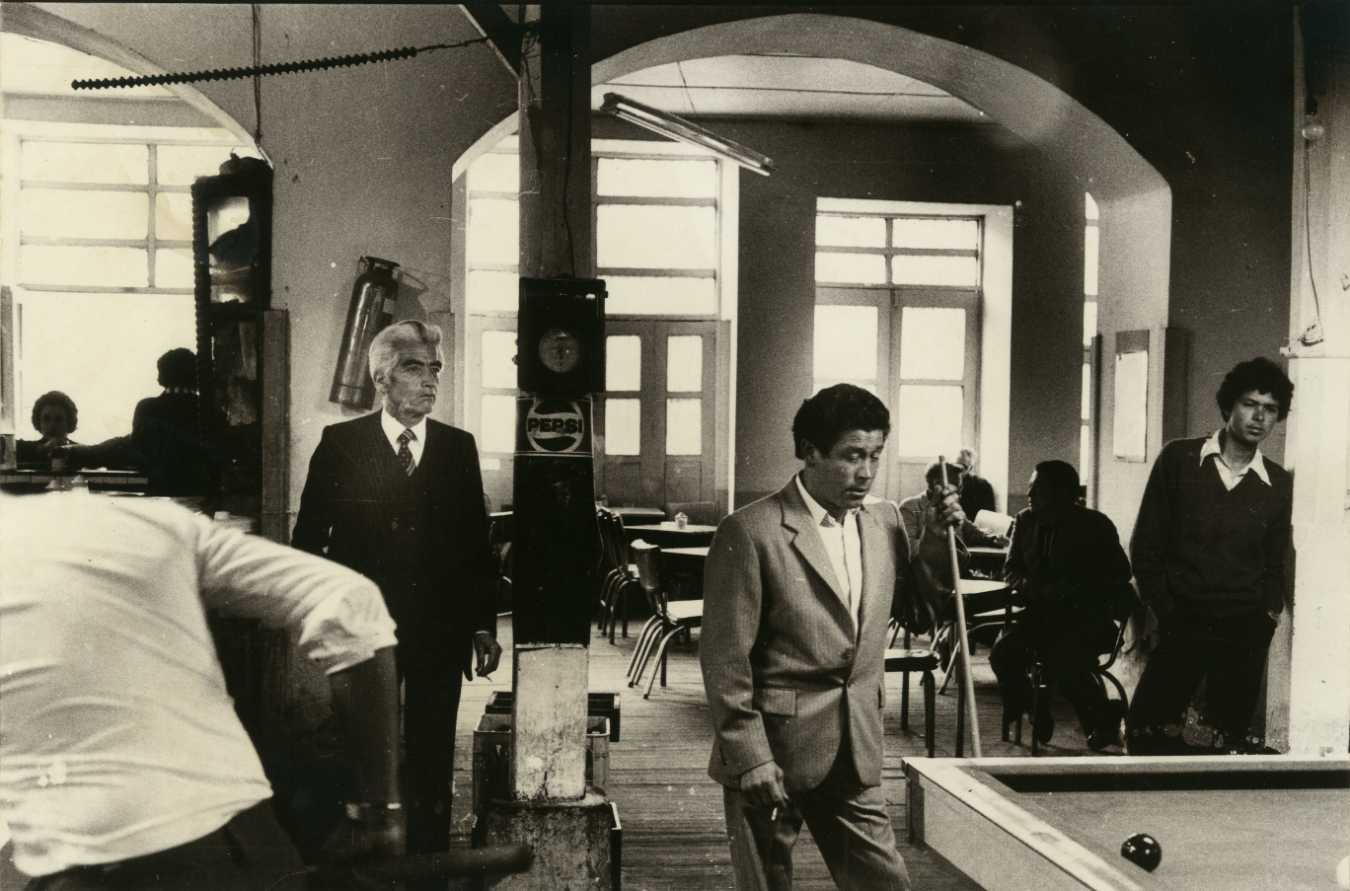

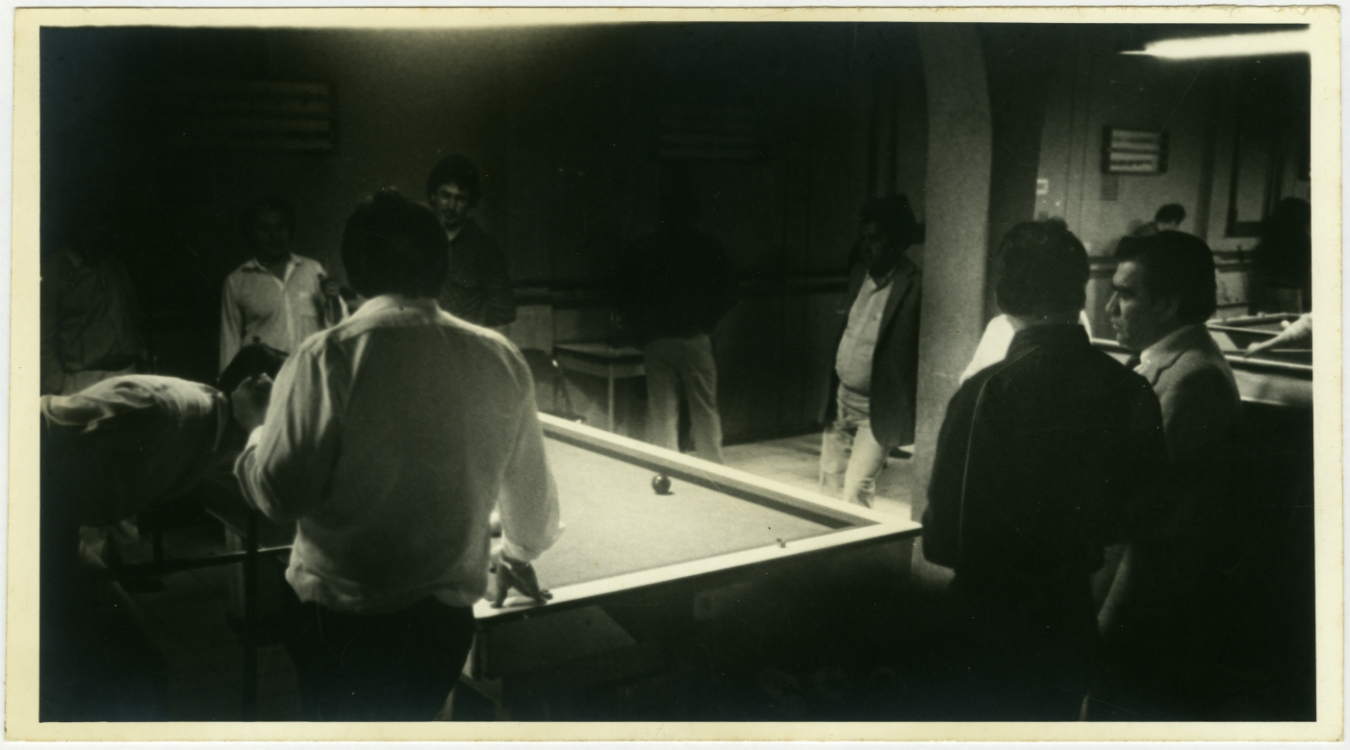

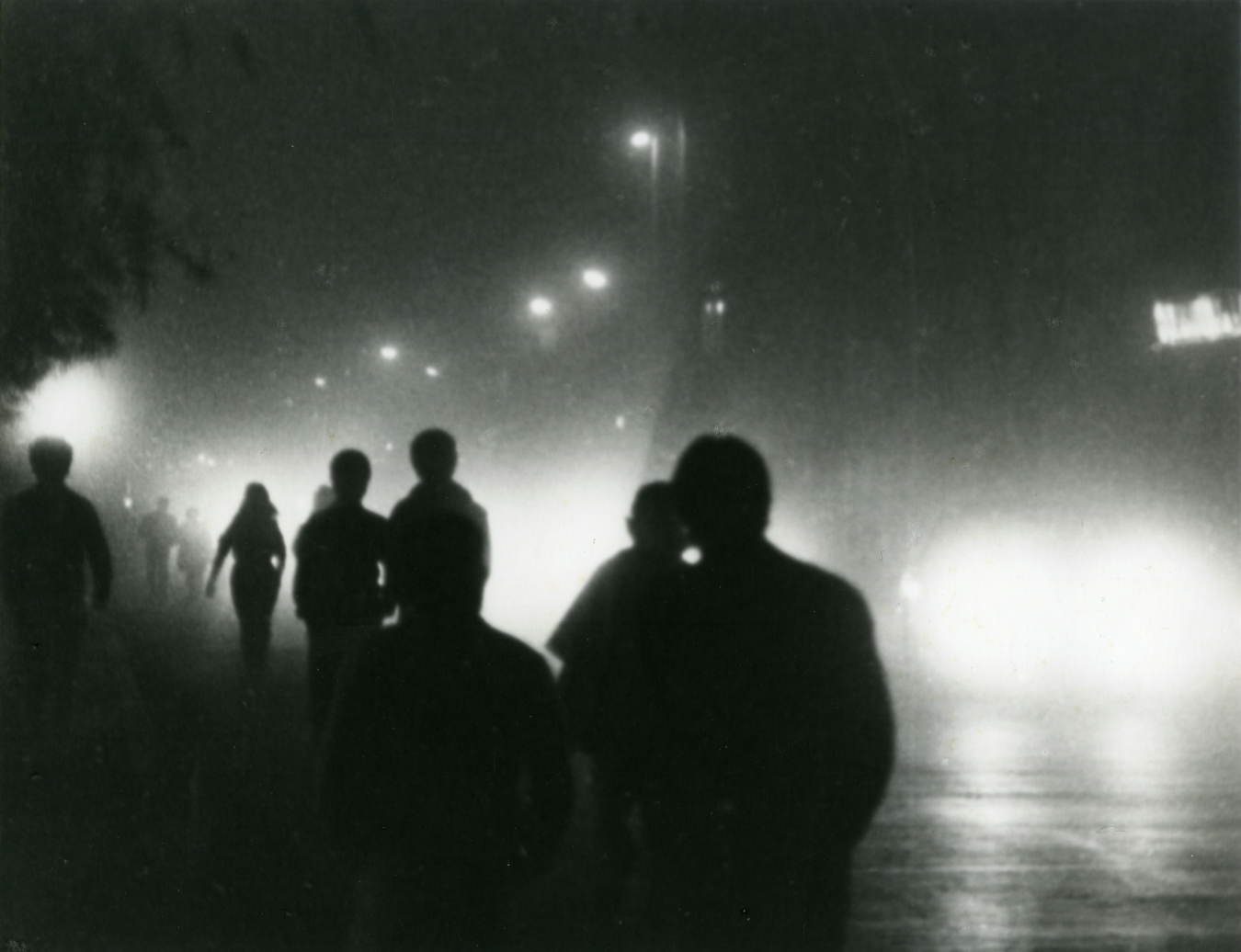

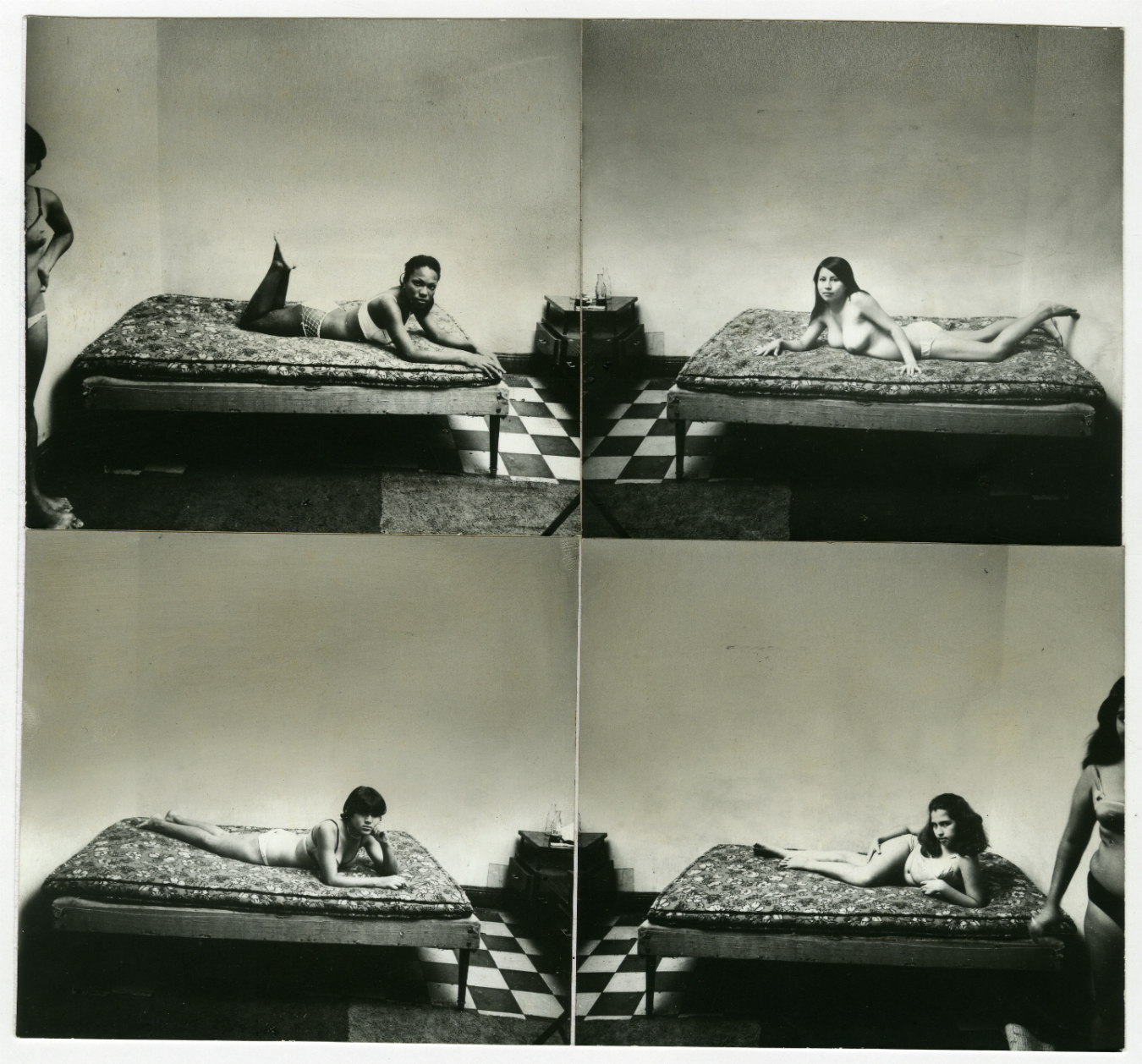

Spurred by this urban expansion, Cali was propelled into being a cultural centre for the country. “The environment was very interesting because the politicians wanted to show the city as a utopian, modern city,” explains Londoño. “But many artists, in visual arts, cinema, and literature—Andrés Caicedo, Luis Ospina—were trying to show a side of Cali that was not the politically-correct side to show.” Franco’s subject matter (the Red Light District, dilapidated housing) exposed a much neglected side of the area. “There was a lot of social conflict, a lot of poverty,” says Londoño. “The artists of the time wanted to show this in order to uncover this hypocrisy of most of the Latin American cities where they tried to say everything is okay, but it’s actually not.”

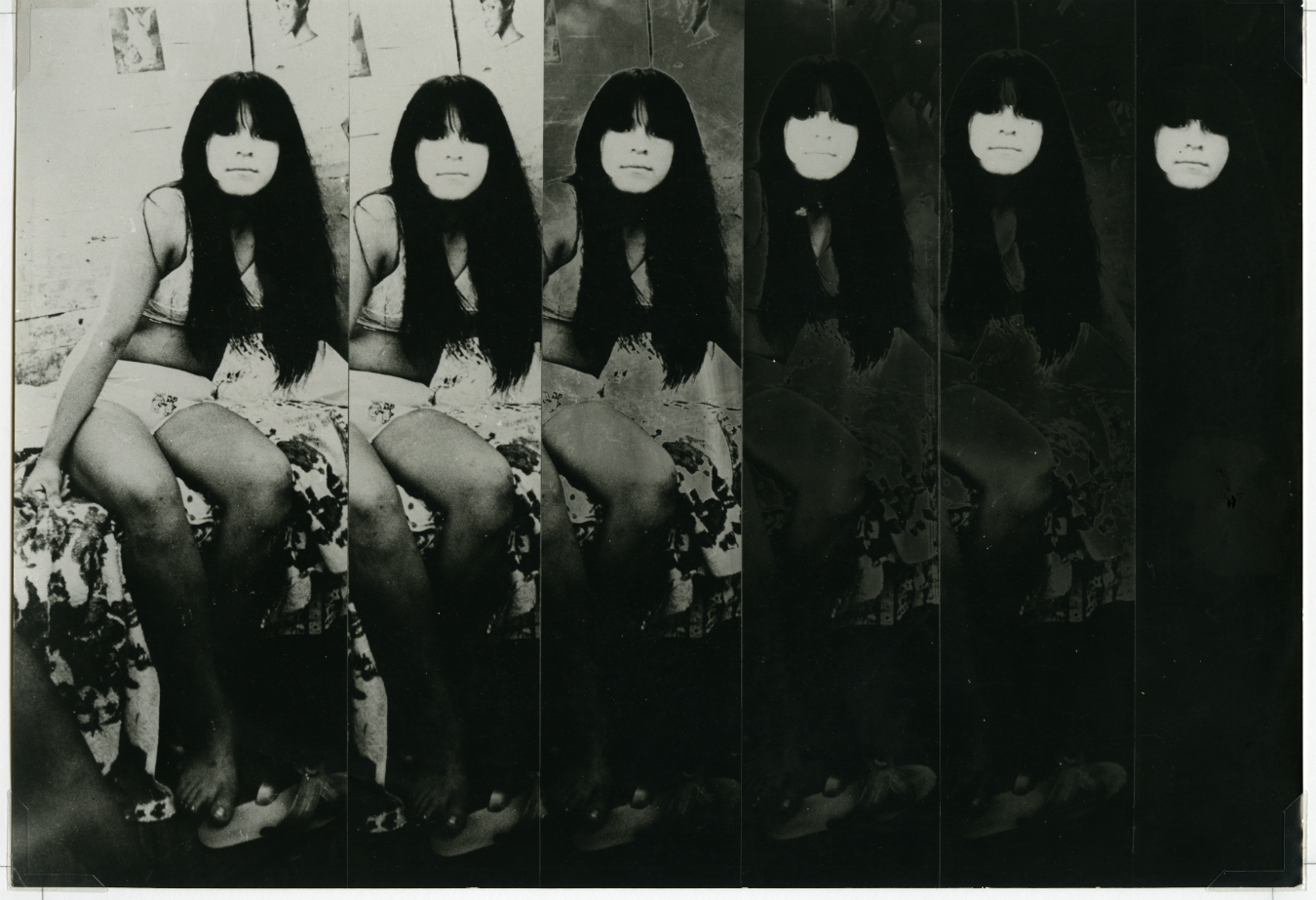

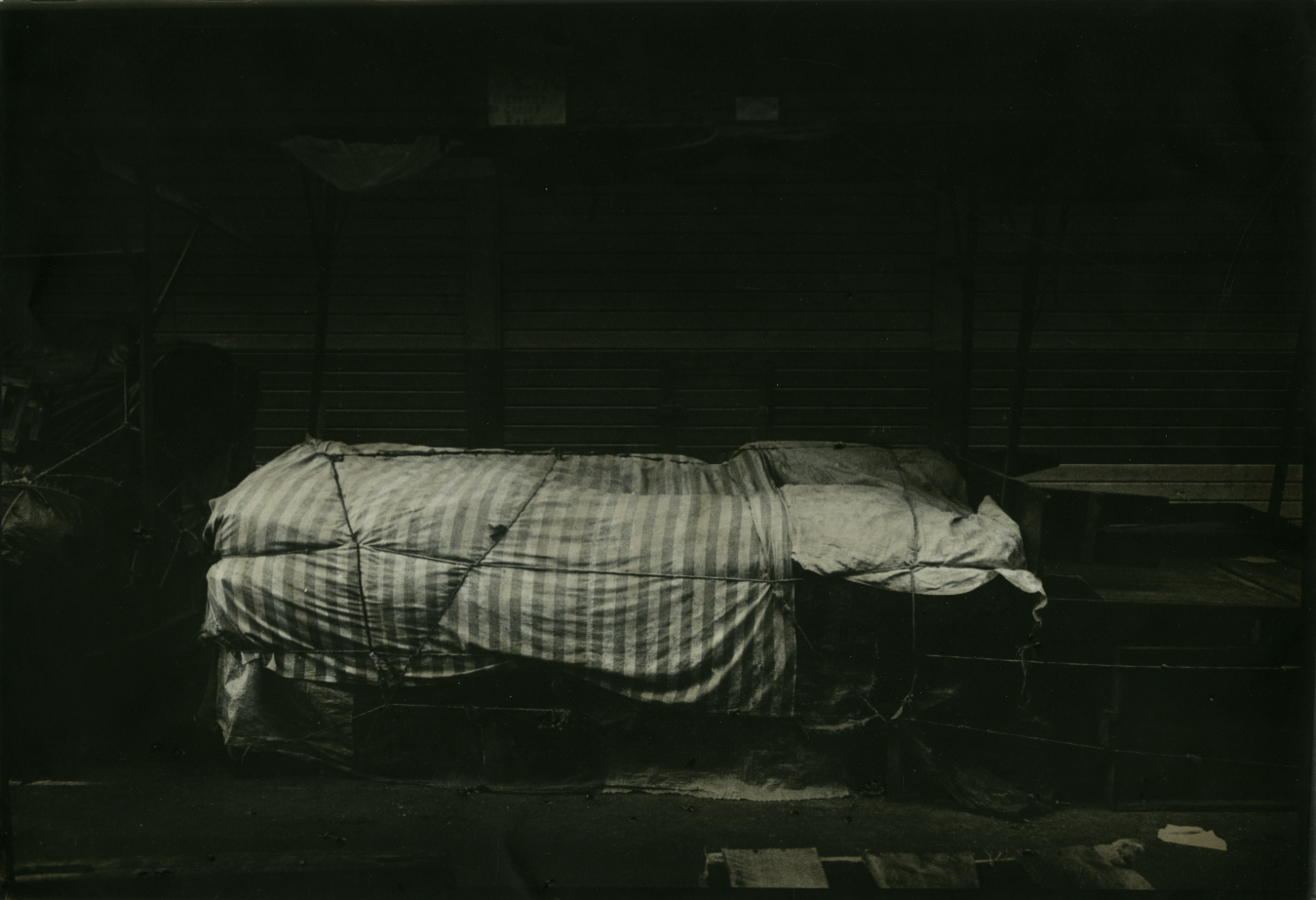

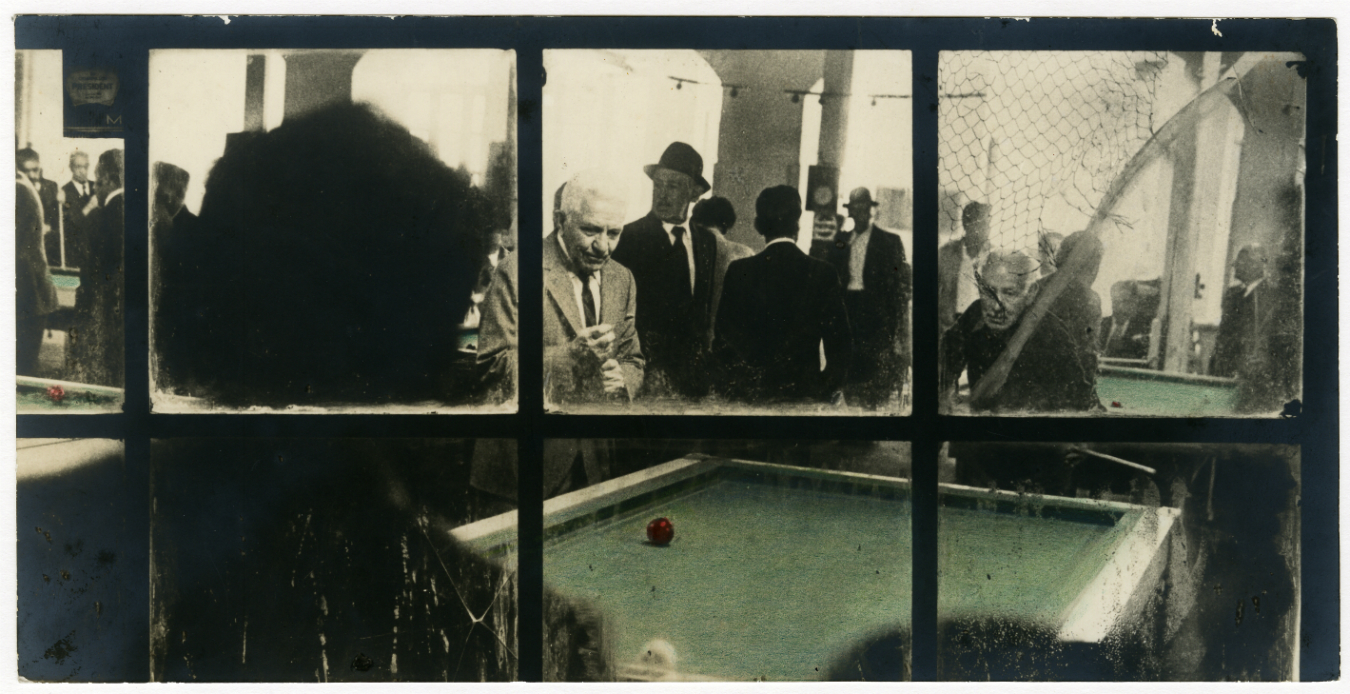

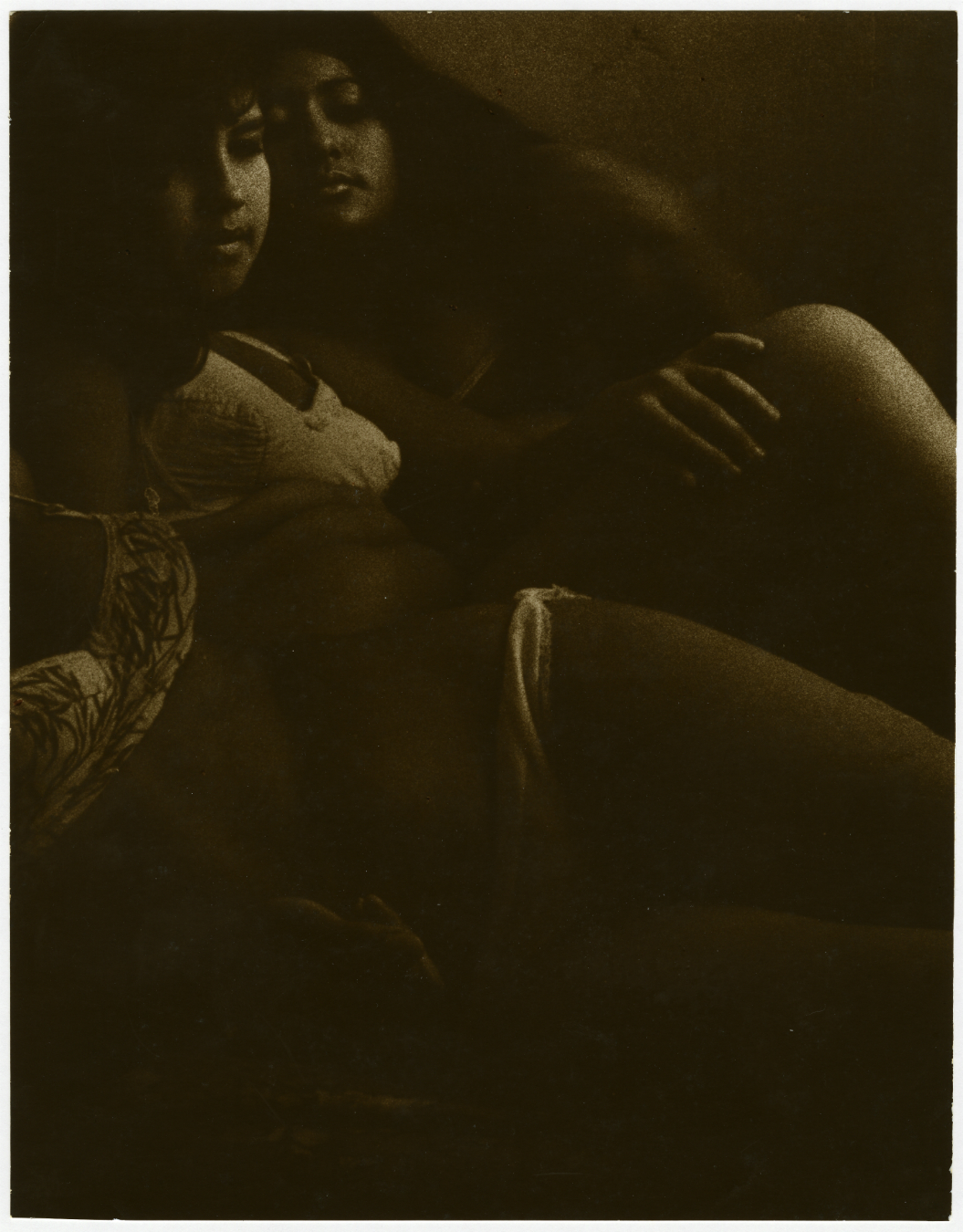

Franco’s images, however, are not straight-forward documentary-style photographs. His process relied heavily on out-of-camera techniques, rearranging and dismantling photos. “Franco would work with his images in a way that was anti-photographic, against photography,” says Londoño. “He would go to the darkroom and play with the chemicals, modify the images, tear up the images to make collages. Many of the practises that he used would be considered a sacrilege to photography.” Sometimes drawing directly onto the images, Franco’s techniques confused and muddied the then clear distinctions between art and photography.

As Franco’s work disseminates internationally, it’s perhaps his distinctive process that will resonate most clearly. “In making a photograph, which is mostly seen as a very pure and objective medium, Franco completely decomposes it and violates it in a way that could be considered very violent,” says Londoño. “I think in that way, people will be amazed to see how many ways a photograph can go.”

Images courtesy Fundación Fernell Franco Cali/Toluca Fine Art, Paris.

_________

Read about the finer things in life. Visit our Arts page.