In 1962, filmmaker James Clavell turned down a trip to Germany where he had been asked to do on-set rewrites of The Great Escape, the blockbuster film he’d written starring Steve McQueen. Instead, Clavell travelled to Vancouver to direct a low-budget revenge film starring unknown actors and produced by a fledgling B.C. company. Although The Sweet and the Bitter (also titled Savage Justice) was a notorious flop, Clavell began an association with Vancouver that would both change his life and spark a new fascination with the Far East in Western film and literature.

Born in Sydney in 1924, Clavell described himself as a “half-Irish Englishman with Scots overtones, born in Australia, a citizen of the U.S.A., residing in England, California, Canada, or wherever.” At 17, he enlisted in the British Royal Artillery and was sent to Singapore to fight the Japanese. His transport was sunk, Clavell was shot in the face by machine-gun fire, and he found himself a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese Army in the notorious Changi prison camp.

In Changi, 10,000 prisoners were squeezed into huts built to accommodate a 10th of that number; 14 out of 15 prisoners died, many from illness and malnutrition. Interned in the camp for three years, Clavell learned to speak Malay and read the Koran. “Changi became my university instead of my prison,” Clavell told The New York Times Magazine in a 1981 interview.

In the late 1950s, Clavell broke into film, penning the script for the Vincent Price horror movie The Fly. During a Writers Guild strike, at the insistence of his wife, April, Clavell wrote his first novel. Set in Changi, King Rat was inspired by his years as a prisoner of war and kicked off “The Asian Saga,” his bestselling series about westerners in Asia. Clavell later used part of his royalty advance to buy a home in West Vancouver.

As Clavell built a name for himself as a screenwriter in Hollywood, Vancouver’s nascent film industry was expanding. In 1956, Oldrich “Oldie” Vaclavek, a Czech immigrant, founded Commonwealth Film Productions (later Panorama Productions), and in 1961 he began construction on sound stages at Hollyburn Ridge in West Vancouver. “With a pipeline now laid to the world’s movie screens,” Vaclavek told The Vancouver Sun, “Commonwealth will make four to eight features here per year to fill that pipeline.”

Clavell first came to Vancouver as part of a multi-picture deal to write, direct, and produce films for Commonwealth; The Sweet and the Bitter was to be the first. Based on a story by Penticton-born novelist E.G. Perrault, The Sweet and the Bitter was, according to Dennis J. Duffy, “suggested by the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II.” A young Japanese woman played by Yôko Tani travels to Vancouver for an arranged marriage to a fisherman, but instead she seduces the playboy son (Paul Richards) of the wealthy businessman who dishonoured her mother. The film began shooting in June 1962, taking 23 days. Filming locations included the industrial waterfront and CPR docks, a North Shore cannery, the Japanese gardens at UBC, the F. Ronald Graham mansion, Little Mountain, and the Lions Gate Bridge.

Asked if he worried about filming in Vancouver weather, Clavell told the Sun, “My friends who light candles are lighting candles. My friends who burn incense are lighting josh [sic] sticks. But if it rains, we shoot in the rain.”

The Sweet and the Bitter “had an awful lot wrong with it,” said Peter Prior, who worked construction on the film. Quoted in David Spaner’s book Dreaming in the Rain, Prior mentioned the extensive amount of film shot (“enough in the can to make about six movies”) as well as Clavell’s habit of stopping every afternoon for a lengthy and elaborate tea service on proper silverware. Cost overruns building Hollyburn studios, a dispute with the British laboratory that was processing the negative, and other financial woes kept The Sweet and the Bitter from being shown for years. It finally premiered at the Orpheum in 1967 to dreadful reviews—Lorne Parton of The Province wrote that the film “violates virtually every tenet of good movie making.”

In the meantime, though, Clavell had received $157,000 from Columbia Pictures for the film rights to King Rat, part of which he used to buy a home in the Whytecliff neighbourhood of West Vancouver. The house at 7165 Cliff Road was previously owned by CBC concert pianist Remette Davis. According to Les Wedman of the Sun, Clavell chose to live in West Vancouver because he loved “the serenity which permits him to work.” Clavell and his wife and two daughters lived there until 1972.

In 1966 the Vancouver Playhouse Theatre Company premiered Clavell’s play Countdown to Armageddon. A year later Clavell wrote and directed the Sidney Poitier film To Sir, With Love. Both Poitier and Clavell took a percentage of the film instead of a salary. When To Sir, made for $625,000, went on to be a box-office hit, Clavell became a multimillionaire.

Clavell split his time between West Vancouver and Hong Kong while writing his second novel, Tai-Pan. The writing process was stressful: he confessed to becoming “obsessed” with the story, to the point it “occupied every waking moment and my dreams.” His solution was to take flying lessons at Sea Island Airport, now Vancouver International Airport, to ease his fixation.

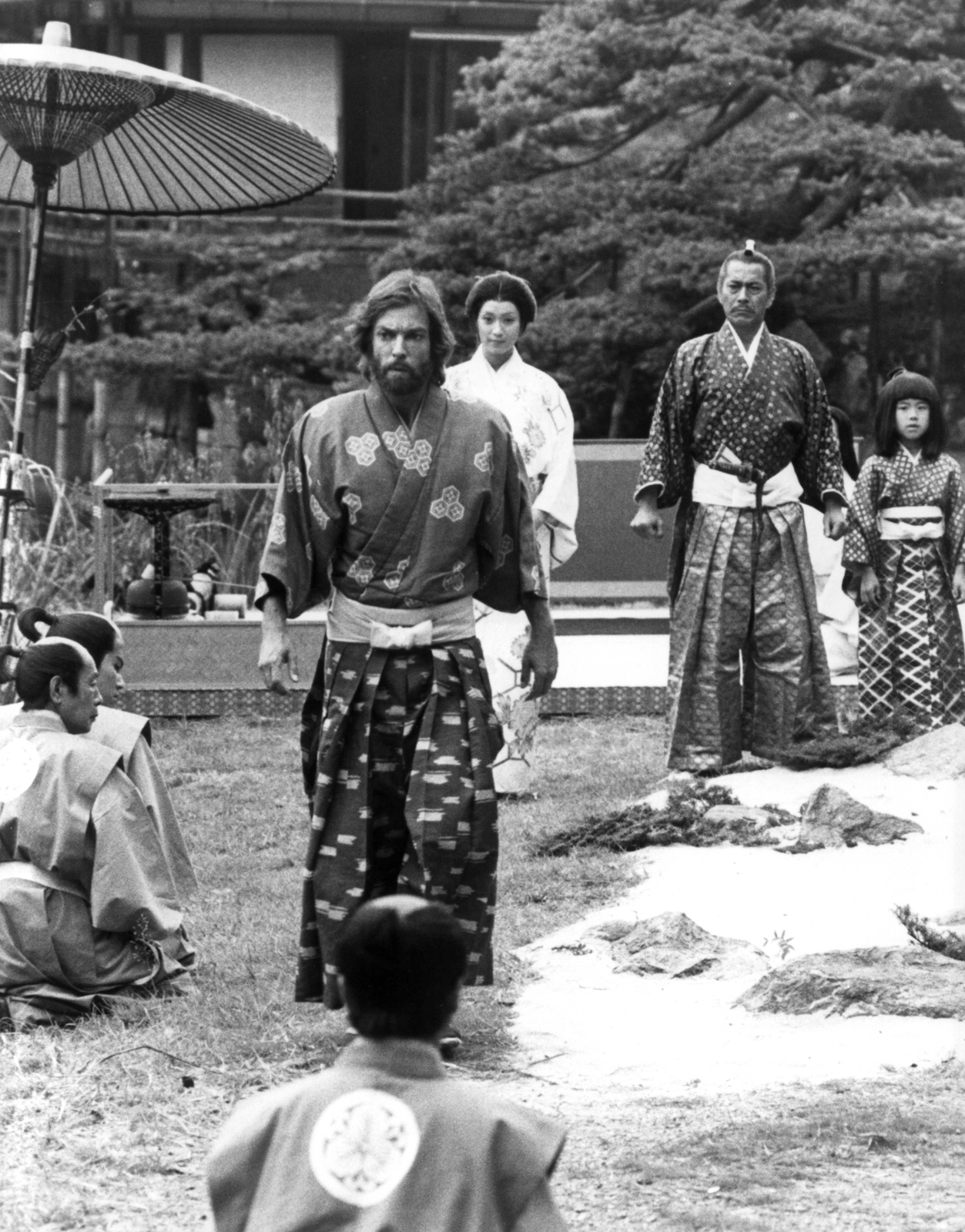

Tai-Pan further cemented Clavell’s success, as did the film adaptation of King Rat. But it was 1975’s Shogun, a novel about a British navigator shipwrecked in feudal Japan, that became his best-known work, not only a multimillion-copy bestseller but also a cultural phenomenon. According to the Times, U.S. President Ronald Reagan wrote a letter of praise to Clavell, and the ruler of an unidentified Arab nation offered him a tanker of oil if he would write a similar book about the Middle East. The 1980 Shogun television miniseries, starring Richard Chamberlain and Toshiro Mifune, was watched by one in three U.S. households, won three Emmys and three Golden Globes, and led to “an entire Shogun industry,” according to The Vancouver Sun, including board games, computer games, and a soundtrack LP. Professor Henry Smith wrote that “Shogun has probably conveyed more information about Japan to more people than all the combined writings of scholars, journalists, and novelists since the Pacific War.”

Although critics argue over the historical accuracy of Shogun, and Clavell’s own attitudes toward “the Orient” are respectful but far from postcolonial, the novel portrays a movement from xenophobia to acceptance. The main character, John Blackthorne, is initially captured by the Japanese, and over the course of the novel he “learns to compare the elegant civilities of Japanese life with the crude vulgarities of Elizabethan England.” As Smith wrote in Learning From Shogun, “The gradual acceptance of Japanese culture by the hero Blackthorne bears the clear implication that the West has something to learn from Japan.”

Clavell’s follow-up, Noble House, was also a bestseller, and in 1986 he commanded the highest royalty advance ever at the time, $5 million, for Whirlwind, his novel of the Middle East. He oversaw a translation of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and wrote one last novel, Gai-Jin, before his death in 1994.

The cultural reach of the former West Vancouverite is still growing. On June 30, 2022, 60 years after Clavell began filming The Sweet and the Bitter, production wrapped on FX Studios’ remake of Shogun. The new series, set to premiere in 2024, was also shot in and around Vancouver, including a set built on the old Flavelle sawmill in Port Moody. The Sweet and the Bitter was a fiasco, but Clavell’s time in Vancouver helped turn the former prisoner of war into what Sun reporter Norman Hacking called “the closest thing to a best-selling celebrity that Vancouver can boast, a man of the world.”