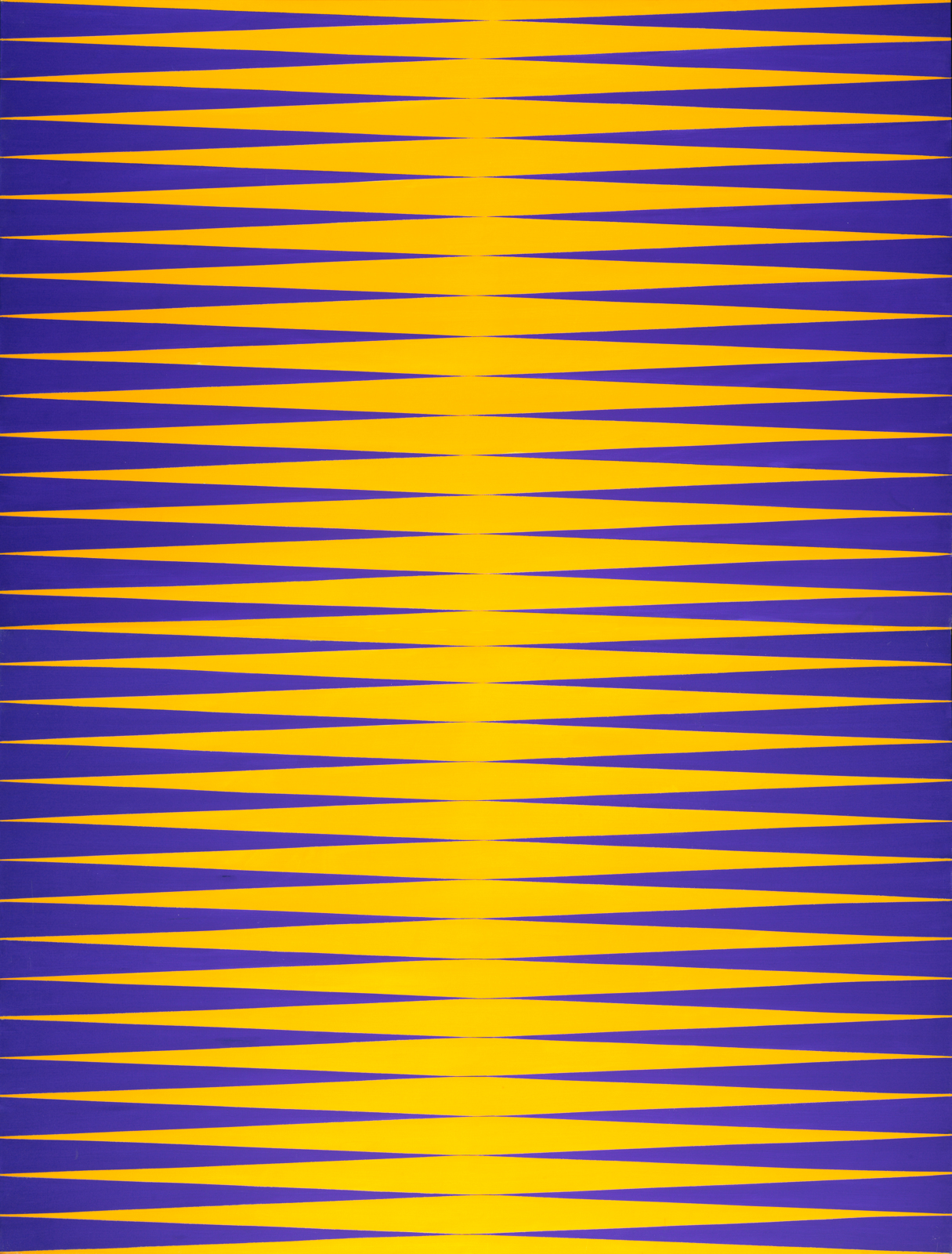

A canvas of blue and yellow geometric forms shimmers on the gallery wall. The abstract, called Radiance Diptych, suggests sun rays and blue sky and is among West Coast artist Joseph Kyle’s final works before he died in 2005. Yellow shapes stack up and down the canvas, each connecting at a central point to create a vertical column of light that spills beyond the painting’s boundaries. The spirit of Kyle’s work comes through—lyrical, radiant, and limitless. His powerful painting and 23 others dating back to the mid-1970s are on view at the Paul Kyle Gallery in Vancouver until May 6.

“His work is a symphony for the eye, just like music,” says Paul Kyle, the artist’s son and curator of the retrospective show, titled The Soul of an Artist.

Joseph Kyle’s passion for abstracts is rooted in the mid-20th century when artists experimented with shapes, colours, and compositions that tricked the eye. Abstract paintings by Kyle’s peers from the 1960s and 1970s are currently featured at the Vancouver Art Gallery’s Hard-Edge exhibition. The Hard Edge movement arrived on the heels of other European-based abstract styles, such as Cubism and Fauvism, and was marked by its freedom of colour and shapes, using an economy of form, well-defined lines, and bold colours. Its cousin Op Art played at creating visual sensations through repeated optical patterns. But Kyle turned away from the Hard Edge and Op Art styles, instead following his own path in which every element of a painting had equal emphasis, creating a harmony of colour and form. This original approach to painting abstracts he called Synoptics.

“He took Op Art to the next level,” Paul says. “Synoptics is about seeing disparate shapes united by colour.”

Kyle’s Synoptica #1, 1999, is comprised of geometric shapes and colours, each colour representing a musical note. The total effect for the viewer is a sensation of harmonious visual rhythms and movement—the concept of Synoptics at work.

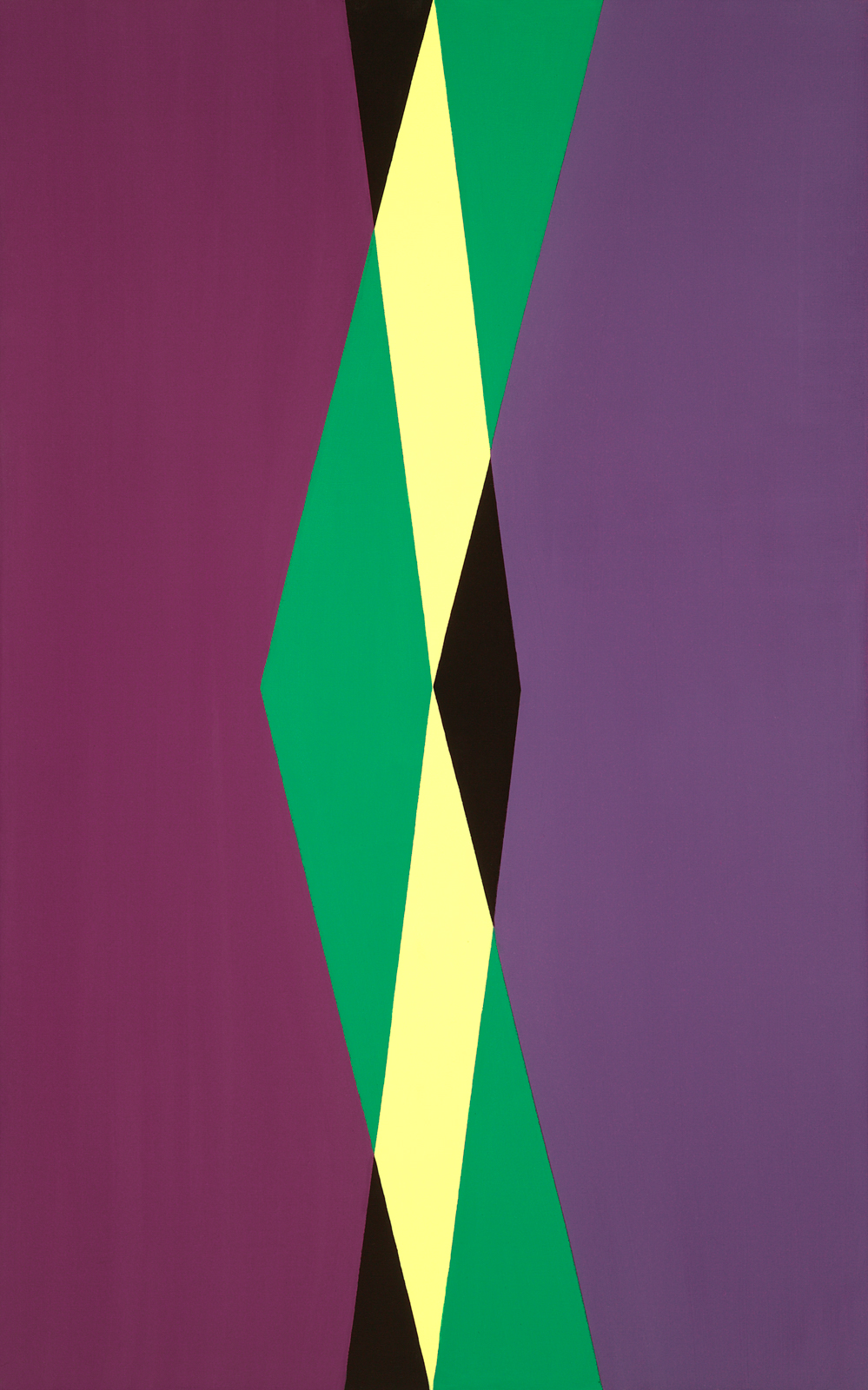

Glenn Gould #6, 1986, is Kyle’s painterly tribute to Gould (1932-1982), a notable Canadian classical pianist. Elongated shapes in yellow, black, and green run up and down the centre of the canvas, bookended with wider forms in burgundy and purple. The composition is informed by Kyle’s keen interest in the connection between abstract art, musical sounds, and mathematics.

Glenn Gould #6 (1986). Joseph Kyle. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 30 inches.

The teachings of Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo also influenced the artist’s work, according to Paul. Joseph Kyle aspired to a “vision of the sublime” in his paintings. The viewer senses a spiritual quality in Entelechy Series 11 #42, 1993. Bold forms are painted in yellows and blues, with the artist employing an overlay on the fields of colour to create a translucent effect.

Not surprising, Kyle developed a kinship with Canadian artist Lauren Harris (1885-1970) of Group of Seven fame. Both men were deeply spiritual, and both focused on painting abstracts. “He was one hundred percent committed to the geometric abstract form,” Paul wrote of his father in the exhibition catalogue.

Kyle was in his 70s when he was honoured by the Canadian Cultural Review board in 1999 for creating art of “outstanding significance and national importance.”

The path leading to this impressive recognition starts in Belfast, where Kyle was born in 1923. His family immigrated to Saskatchewan in 1930 and, a decade later, Kyle travelled to Vancouver, serving four years in the navy. In 1946 he married Annette Roberts and soon after the couple moved to Montreal, where he studied music composition at McGill University. The pair returned to the West Coast in the mid-1960s and Kyle found various lines of work, including at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and Simon Fraser University.

The post-war era was a time of dramatic upheavals and fresh ideas. “New technology always produces new art,” Kyle wrote in an article for Arts Canada magazine in 1968. “It is in this way that man invents an image of himself that enables him to relate to a new reality.” While Kyle and his wife were busy raising six children in their West Vancouver home, he networked with creative people across the Lower Mainland’s budding cultural community.

Entelechy series II #42 (1993). Joseph Kyle. Acrylic on canvas, 72 x 60 inches.

In 1967, Kyle co-founded Intermedia Society with visual artists Jack Shadbolt (1909-1982) and Victor Doray (1930-2007) and served as the first director. The group operated out of a four-storey building at 575 Beatty Street in downtown Vancouver. Intermedia attracted a wide range of visual artists, performers, and musicians, gaining a reputation as experimental, interdisciplinary, and visionary. When the Intermedia Nights festival was held at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1968, the Province newspaper noted that those who attended experienced “a cultural arousal” as never before seen in the city. Intermedia’s impact was enduring, despite closing in 1973. Among the spinoff arts groups that still exist are Western Front and Video Inn.

The same year Intermedia folded, Kyle and his family moved to Victoria. Three years later he founded the Victoria College of Art, teaching and serving as principal for 25 years. Whether painting in his studio or sharing his talent with students, Kyle kept his creative flame alive. In 1981, he achieved satisfaction in both his worlds, leading the entire art school in a year-long experiment with geometric abstract painting.

After retiring from the college in 1988, Kyle spent long hours in his studio. He made hundreds of sketches, working out his compositions and labelling colours with a letter. When he transitioned to the canvas, he used acrylics and painted by hand without any digital or mechanical aid. Typically, he created a series of abstract paintings, each consisting of 50 or more works.

Synoptica #1 (1999). Joseph Kyle. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 66 inches.

His canvases were large. Radiance Diptych, for example, is painted on a canvas six feet wide and nearly eight feet tall. A photograph in the exhibition catalogue shows Kyle applying a tradesperson’s wide paintbrush to a canvas. In another image, he holds a hair dryer over a wet painting, a method to speed up the drying process. Despite his keen interest in music, Kyle did not listen to anything while he worked, preferring silence in the studio.

Kyle’s senior years were remarkably prolific. He maintained his link to Vancouver, travelling from his home in Victoria for shows at the Alexander Gallery, then owned by his son Paul, and the Bau-Xi Gallery on south Granville Street. His final exhibition was at the Buschlen-Mowatt Fine Arts Gallery in 2002.

Today Kyle’s paintings are held in collections in Canada and around the world and at several private and corporate locations. He is among 14 British Columbian artists to have a painting displayed in the West Building of the Vancouver Convention Centre, all chosen for their “innovation, creativity, and international influence.” (The Convention Centre’s BC Artists Gallery can also be viewed online.)

The fresh and dynamic works displayed at the retrospective honour Kyle’s important legacy and offer the visitor a meaningful visual experience. Joseph Kyle was truly a remarkable artist, always moving forward creatively and always toward the light.

The Soul of an Artist is showing at the Paul Kyle Gallery, 4-258 East 1st Avenue, from February 15 to May 6. Read more local Arts stories.