If people know one thing about Van Gogh’s paintings, it is usually that his thick, swirling brush strokes give the viewer the illusion of movement. Whether the subject is wheat fields, the night sky, or a vase of sunflowers, the Dutch master’s most easily identifiable trope is his ability to convey the pulse of life.

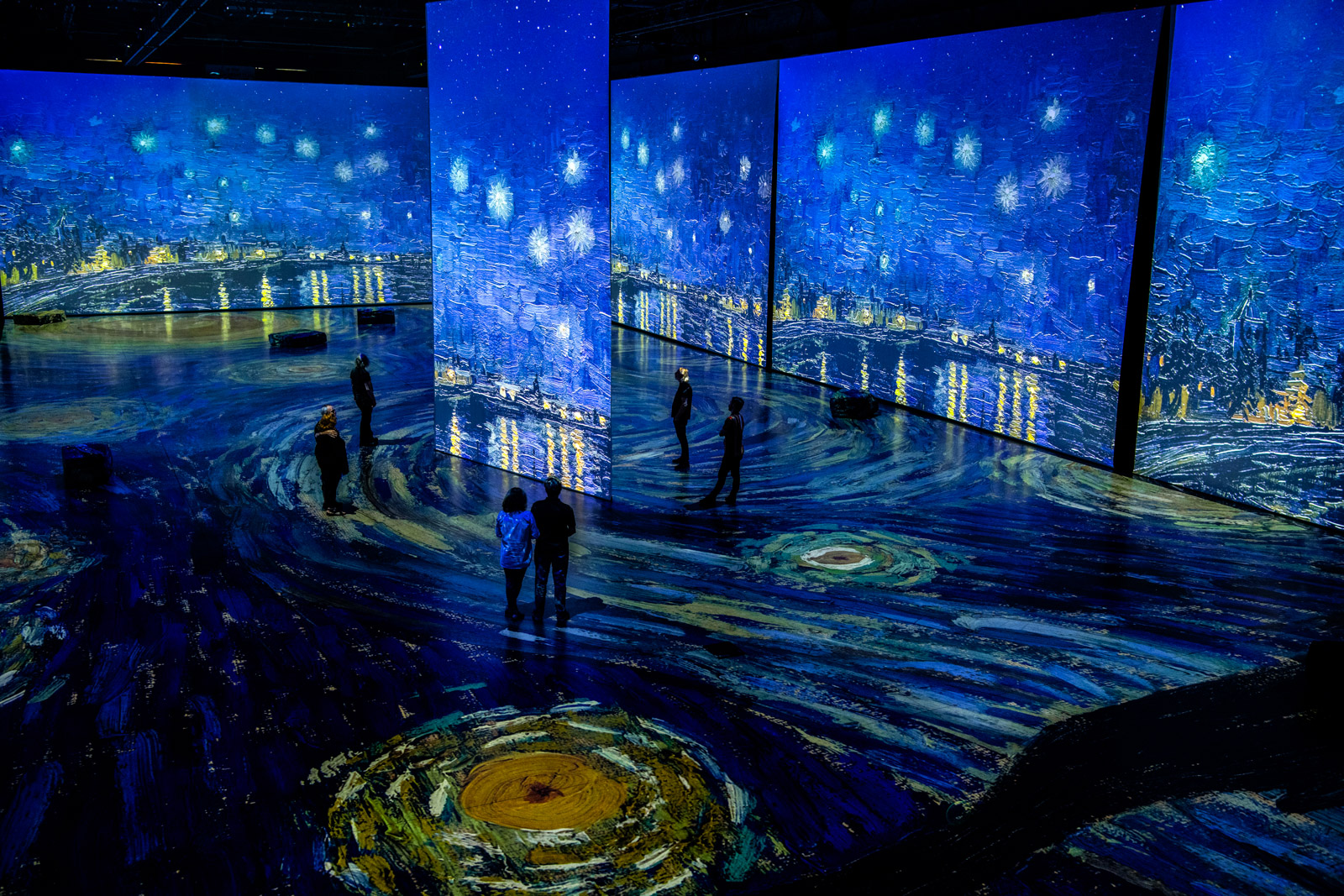

In a custom-constructed room in the Vancouver Convention Centre, that pulse is taken a very large step further in Imagine Van Gogh, where digital projections of the artist’s work are plastered across walls some eight metres high. Not only that, the images scroll up and down as classical music fills the space, and elements from the paintings also cover the floor. It’s an immersive experience that attempts to put us “inside” the art.

Does it work? Well, it’s definitely unlike any other art exhibition I’ve seen, and there’s a novelty to the concept that is engaging. Whether it deepens our connection with or understanding of Van Gogh’s work is another matter, but, as my teenage son who accompanied me pointed out, it’s not as if we are going to see these paintings in real life any time soon.

Imagine Van Gogh. Photo by Laurence Lebat.

And it’s easy viewing: the images are blown up to enormous proportions, there are multiple paintings displayed (in themes) at any given time, and the usual hallowed silence of an art gallery is eschewed by the nonstop music. You don’t require a lot of concentration, because the artworks change every couple of minutes and your eye is inevitably drawn to the scrolling images. The music may or may not help your attention span, but the collection of classical “greatest hits” that includes Lakmé and “Air on a G String” won’t win any awards for originality.

It’s a spectacle—and one we can expect to be reprised; Monet is already being given the same treatment. But there is no escaping the sense that the spectacle eclipses the soul of the art, that the flattened-out, blown-up, pixelated images can do nothing more than chart the artist’s life and work. The overwhelming thought that fixed in my mind while experiencing this exhibition was that it was a perfect illustration of Walter Benjamin’s theory of the “auratic effect”—that the reproduction of an artwork diminishes its power.

On the other side of Burrard Inlet, there is another summer exhibition at the Polygon. Feast for the Eyes attempts to chart the history of photography in food through art, cookbooks, commercial photography, and snapshots. Like a traditional smorgasbord, it is a pick and mix of choice cuts and crowd pleasers that, with a couple of notable exceptions, are unlikely to upset your palate.

Sharon Core’s Still Life with Oranges, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York.

Our obsession with what is on our plates and how it looks has, of course, never been more pronounced (hello, Instagram), and the pure aesthetics of what has been considered appetizing has changed over the years. A selection of 1970s recipe cards from Weight Watchers is the best representation of that—a swath of gelatinous creations set in moulds and oversaturated brightly coloured dishes (moulded asparagus salad, crown roast of frankfurters, several pale-pink concoctions involving mackerel…) likely to slim you down by simply putting you off food for life.

Elsewhere there are beans on toast (Martin Parr), a man shovelling a tsunami of spaghetti into his mouth from a dish sitting on a checkered tablecloth (Weegee), and luncheon meat as kitchen tiles (Sian Bonnell). Bucolic snapshots of old family picnics rub shoulders with examples of fine art photography, still lifes progress from classically arranged fruits and vegetables to shots of half-eaten burgers and precisely lined up rows of peas. There are some political punctuations—JR’s longtable dinner across the U.S./Mexican border, shots (from the What the World Eats coffee-table book) of what a week’s groceries in different countries looks like.

Carl Kleiner’s Hembakat är Bäst, 2010. Courtesy of Carl Kleiner and Evelina Kleiner.

But mostly, this is a Western-focused collection interested in how our relationship with food is expressed through images. A light overview, this is another show where you can take your family bubble and everyone will find something to either inspire hunger or put them off their dinner.

These are not exhibitions to blow your mind at the power of art, but they are diverting and different. And anything that can capture our imagination and transport us elsewhere (even if only metaphorically) at the moment is a welcome distraction. Light and enjoyable is absolutely fine and worthwhile and, frankly, probably as much as our understimulated brains can cope with right now.

Read more local Arts stories.