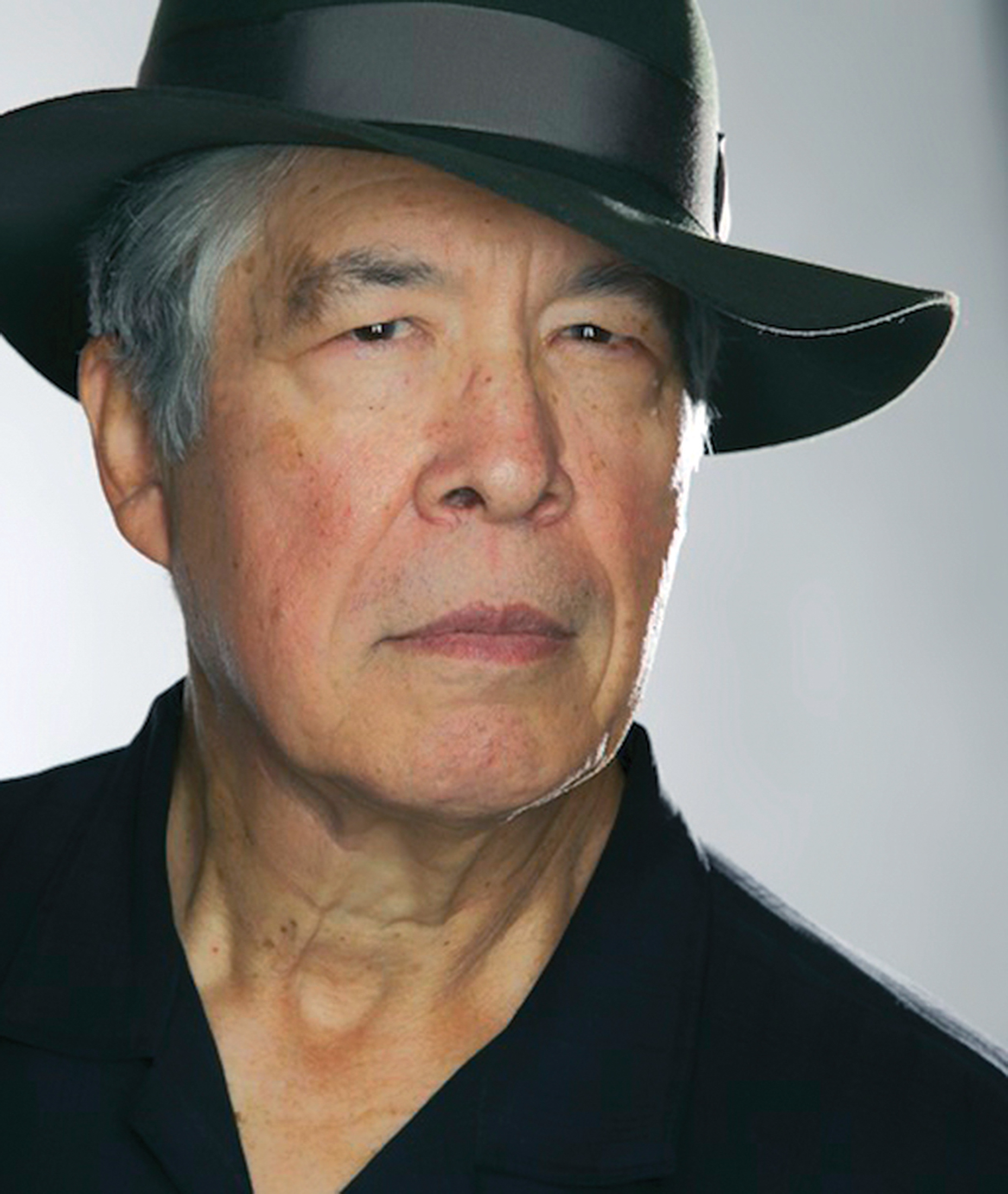

Thomas King isn’t sure what to make of the hundreds of thousands of Canadians who trust his voice. In the first two decades of his career, the award-winning author was a voice of reason, humour, and conscience across an array of lectures, and hours of radio shows. But the success of his first non-fiction book The Inconvenient Indian, which has yet to leave the bestseller lists after eight years, catapulted him to a strange, stratified place in the Canadian intellectual landscape.

For some, The Inconvenient Indian is the first or only text of his that comes to mind, despite its anomalous position in his body of work.

“The hard thing for artists of colour in Canada is that there is the expectation that we are everything,” King says over the phone from his home in Guelph. “That we’re activists, that we’re writers, that we’re philosophers, that we’re community builders, and the fact of the matter is we can’t be all those things. No individual can be all those things.”

King doesn’t say this as a way to ward off additional responsibilities; he speaks as someone who’s actually tried all those paths. He has, at various times, wanted to be everything.

“One of the great sorrows in my life is that with all the energy that so many people have put into changing the landscape for Aboriginal people in Canada, very little has happened at the political level.”

He picked up fiction while he was finishing his PhD, then saw the American Indian Movement first-hand in the 1980s. He wrote provocative, richly detailed novels and was lured to television development by the CBC in the ’90s. And, dismayed by calculated political inaction on matters of life and death for Indigenous peoples, King ran in his local riding in the 2008 federal election.

In their own way, each of these larger institutions repelled King, and so, repeatedly, he has returned to the page, a space unconstrained by the public concerns of media relations. The major book prize bodies in this country have never been shy about nominating King for awards, and this acclaim has essentially allowed King to pursue what he wants in his fiction, even before the success of The Inconvenient Indian.

“I discovered I was better as a writer than I was as a frontline activist, basically,” he says. “And so I settled down into what I am now.”

About that: while the provocative iconoclasm of his earlier novels is no longer a major feature of his work, whether killing off John Wayne in a would-be heroic western (Green Grass, Running Water) or painting colonial landmarks out of the horizon (Truth and Bright Water), King is in the middle of the most productive stretch of his career.

Including his genre fiction, a long-in-the-works poetry collection, and the Giller-longlisted Indians on Vacation, King has released five books in the past three years. He says his next major novel is already scheduled for May 2021, and another two books are in the works.

This isn’t to say that King is, in writing at his usual pace, immune from the turmoil of the world. He’ll watch, even if he’s seen the stories play out before. Even in the nationwide solidarity people showed the Wet’suwet’en, King notices the familiar cycle: where activists demand that people notice, media co-opt their images and language, governments delay, and commissions issue reports they’ll ignore.

“It doesn’t feel very different, to be honest with you,” he says, referring to this year’s tide of protest action seen first in the nationwide rail blockades preceding the pandemic, followed by months of Black Lives Matter solidarity marches. “I think one of the reasons that these things come around, again, is that they don’t get settled.”

“One of the great sorrows in my life is that with all the energy that so many people have put into changing the landscape for Aboriginal people in Canada, very little has happened at the political level.”

The protagonist of his latest work, Indians on Vacation, is Blackbird Mavrias, a disillusioned ex-journalist. He wasn’t laid off, as so many have been; he left after one too many compromises. The main plot, a hunt for answers to an obscured part of family history, includes a major red herring or two, the incursion of real-world headlines, and what can certainly be called an intentional refusal on King’s part to indulge in satisfying narrative development. The real interest, it seems, is how rootlessness manifests.

“In my books, I’m really trying to explain the world to myself,” King says. His fictional worlds, once full of co-existing facets of fable, dream, and reality, are now concerned with animating more modest action. The question is how to keep going, even as the tangible possibilities for change are, at least in the short term, hard to imagine.

There is one possible answer in Michelle Latimer’s new award-winning documentary, which doesn’t just adapt The Inconvenient Indian but uses it as a springboard to explore different artistic responses to the history King has always confronted in his work.

Latimer, to some extent, is doing the work King once felt compelled to do: there are activists, there are writers, there are community builders in the film. She is continuing and developing what King and other artists of his generation started. But in this film, King is more of a framing device than a central figure: after years of taking on every battle he encountered, here all he has to be is a novelist.

Thomas King will be appearing in a virtual talk at the Vancouver Writers Fest on October 24. Read more stories on the Arts.