The textile arts are rife with baggage. In Canada, it can be unclear where they fall on the spectrum: they could be anywhere between the antiquated, reductive view of the medium and the hyper-progressive, feminist banner version. Recent shows at Vancouver’s Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery and Contemporary Art Gallery posit textiles as coming into their rightful place: next to the painting, the finest of forms.

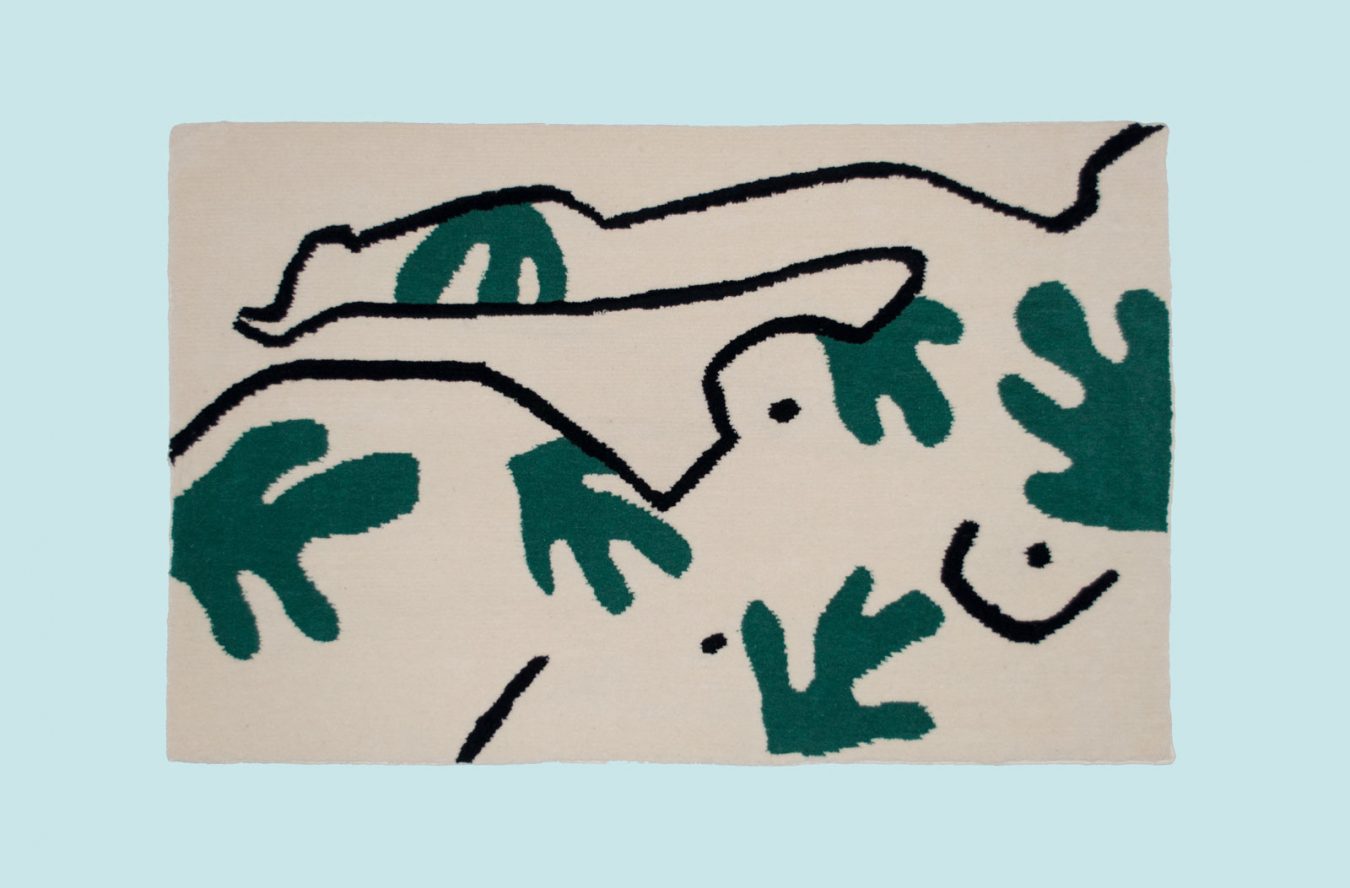

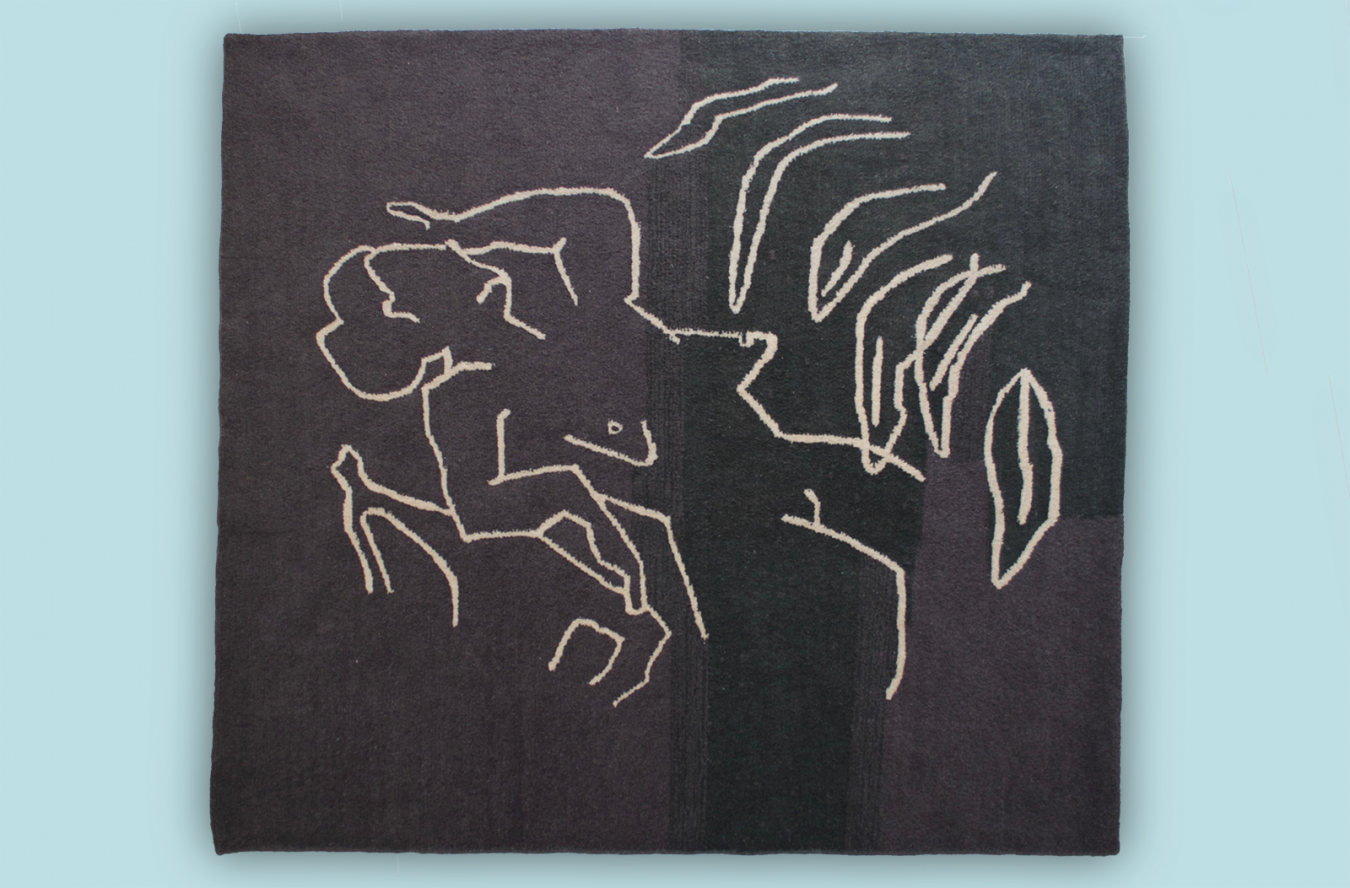

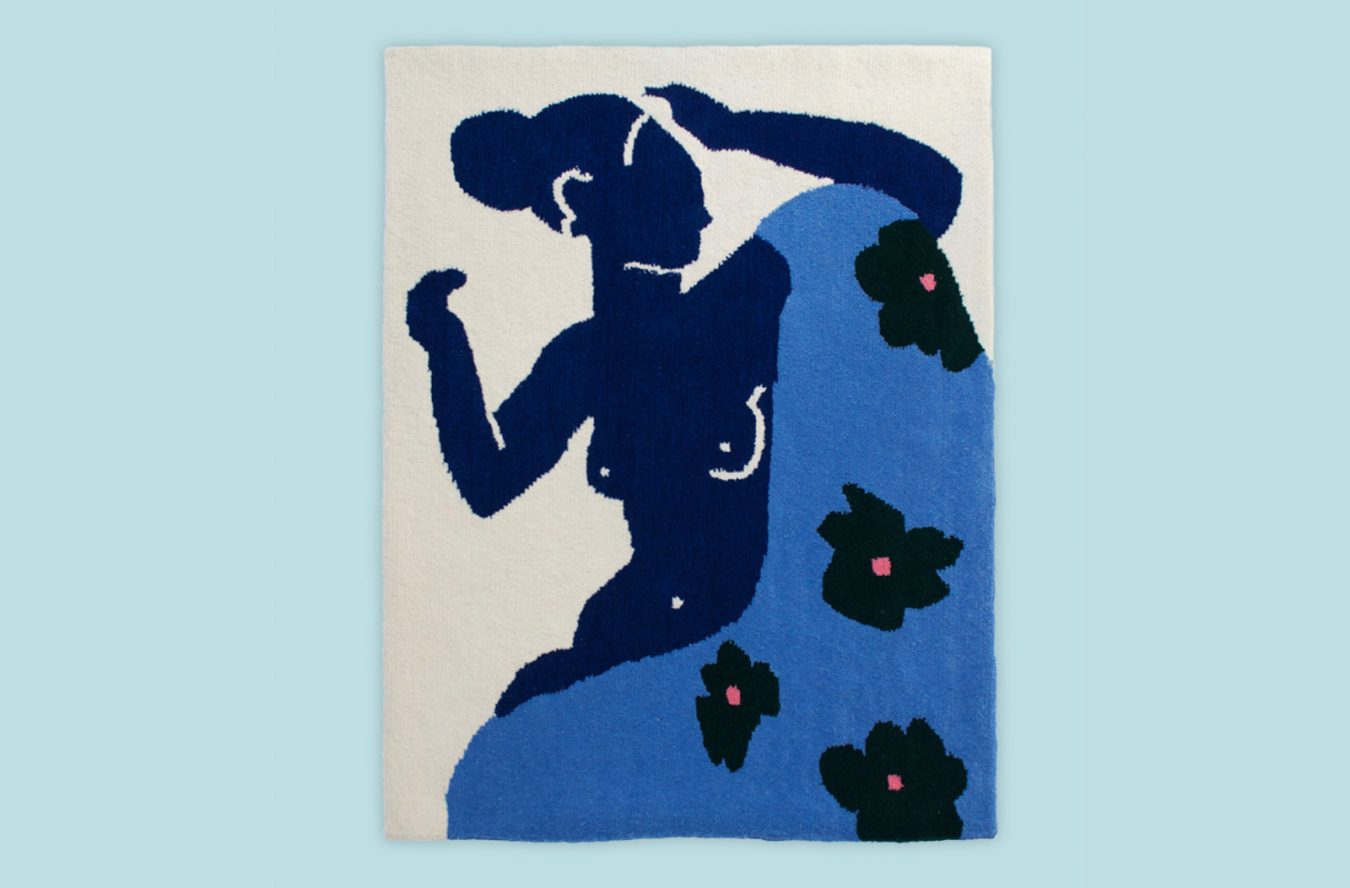

Textiles have long been classified as decorative or applied arts, and more derogatorily (to both half the population and to textiles) as “women’s art” or “women’s work.” It seems as though one of the textile’s defining characteristics is indeed its contested nature; these pieces are mutable, fuzzy, lovely things that stand in as substitutions for systematic and ongoing discrimination in the art world and beyond. However, there is much more to the textile than what meets the topical art critic’s eye. It’s at the crossroads of this controversy and highly skilled whimsicality that one finds the sexy, minimal rugs and pillows of Vancouver-based Julia Mior. Her work enables the medium to sidestep its baggage in order to explore and celebrate a softer side of femininity.

“A lot of people who buy my work want to hang them, but that isn’t necessarily how I intend it.”

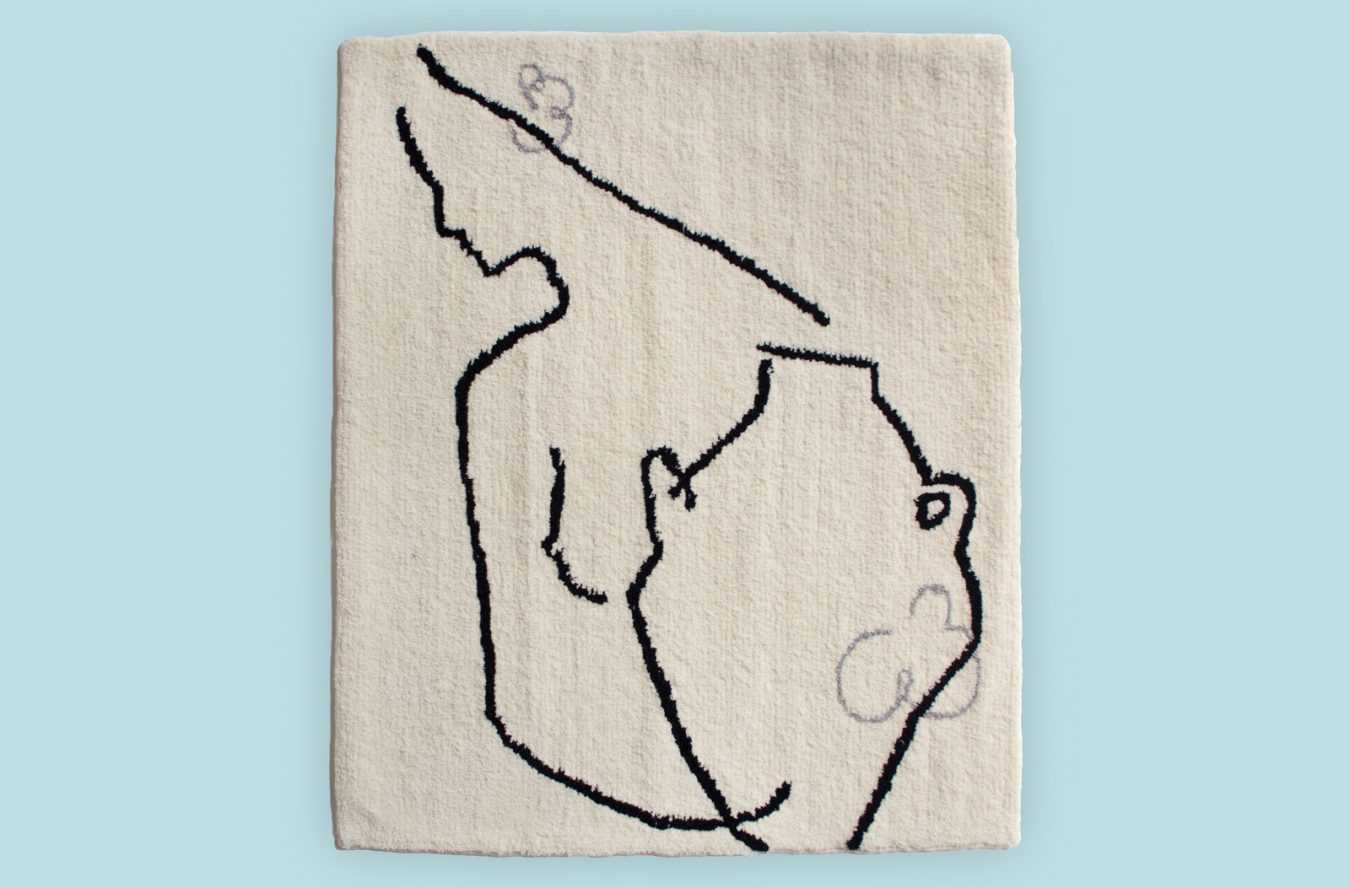

“I’ve been weaving rugs for about a year now,” Mior says, though she adds that she always knew she would work in the arts in some way. Her education took her to Capilano University, and then Emily Carr University, where she studied painting and later got into embroidery. “Weaving is so much more immediate than embroidery, which makes it very therapeutic,” she reflects. Mior purchased a tufting gun from a sketchy online shop, half suspecting it would never show up—but when it did, she taught herself to use it. As one might imagine, this was not an easy task. “It took me forever to figure out how it worked. It only works in one direction, and I didn’t understand that part,” she says. But now that she has honed the tool of her trade, Mior has started to really branch out and experiment.

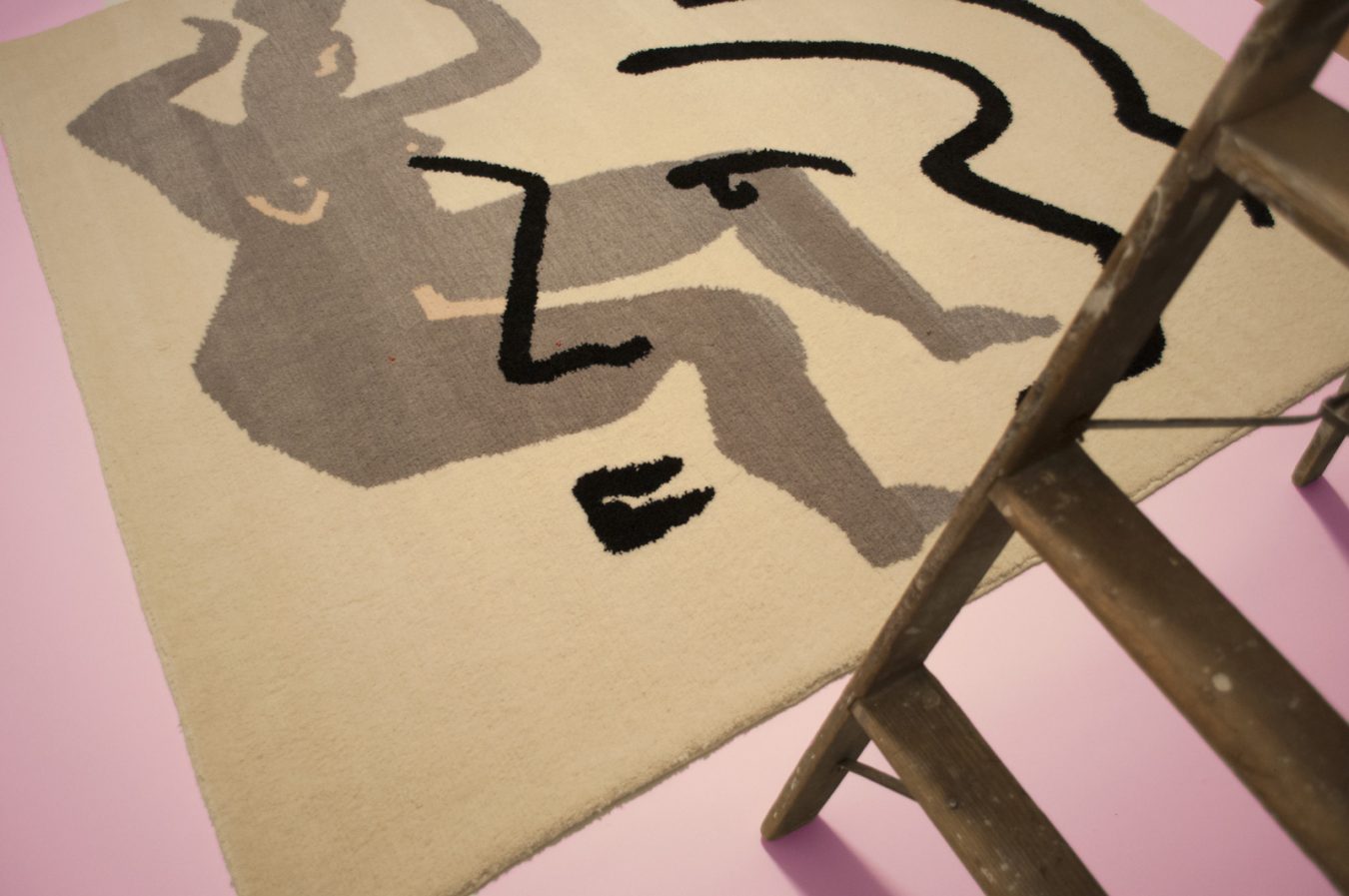

She works with recognizable subjects: minimalism, abstraction, the female nude. The products—austere and cleverly emotive rugs and pillows—are the result of nearly 40 hours of labour (and at least one manic drawing spell, where Mior systematically works out the abstraction of her chosen figure). Part of what sets Mior’s textiles apart from contemporary museum discourse is that she does, indeed, want people to use them. “The rugs are made to be put on the ground,” she says, seated at Cartems Donuterie on Main Street. “A lot of people who buy my work want to hang them, but that isn’t necessarily how I intend it.”

The implications of the female body cast in textile and under one’s feet are myriad. It’s an act of domination, to “walk all over” somebody, and Mior knows this. Her works force viewers to look at the female body and consider their relationship with it—both on the rug, and in the world—a relationship which is developed in dialogue with historical artistic practice and social discourse. What moves Mior’s work beyond the tense negotiation for space and ownership is her personal break with these histories. It’s not a violent break, and she does grapple with the conditions, but it places a pause on some of that baggage: her work is, in part, free from the weight of having to be tough, or to prove its value in art. The pieces, and their content, can embrace a space of kindness more freely. Especially with her pillows, Mior recasts the caring, “domesticated” woman from something shameful to something warm; the items capitalize on the empathetic, considerate embodiment of femininity that is so often discouraged in men and women alike.

For many, just being in public feels a bit like a protest, like a war might break out at any moment—it can seem dangerous to be sensitive, like we’re letting our guards down. Mior’s nudes celebrate this gentle, soft inclination (which is by no means exclusive to one gender) and encourages the viewer—or the person snuggling the pillow, or stretched out on the rug—to be equally gentle and soft. Mior reminds us that beyond the white cube, textiles serve a purpose in life that few other artforms can: they offer a tactility that facilitates a specific kind of comfortable living. Despite the charged imagery she produces, absolutely rife with discussions of misogyny, racism, and discrimination, Mior manages to reclaim the kindness of the textile—without ever undermining its importance or validity to the broader history of fine art.

View more of the Arts.