Kerry James Marshall walks into Vancouver’s Rennie Museum at a little past noon, wearing a faded sweater and baseball cap frayed at the edges. Smiling broadly to a group of journalists standing out front, he introduces himself, shakes hands, and then abruptly turns to climb the stairs to the main hall. Before he reaches them, though, his curator calls him back, introducing the sheepish men with their hands clasped behind their backs as those he’s scheduled to tour through his new exhibit.

“Oh,” he says, laughing. “You were standing there so official, I thought you were Secret Service or something!”

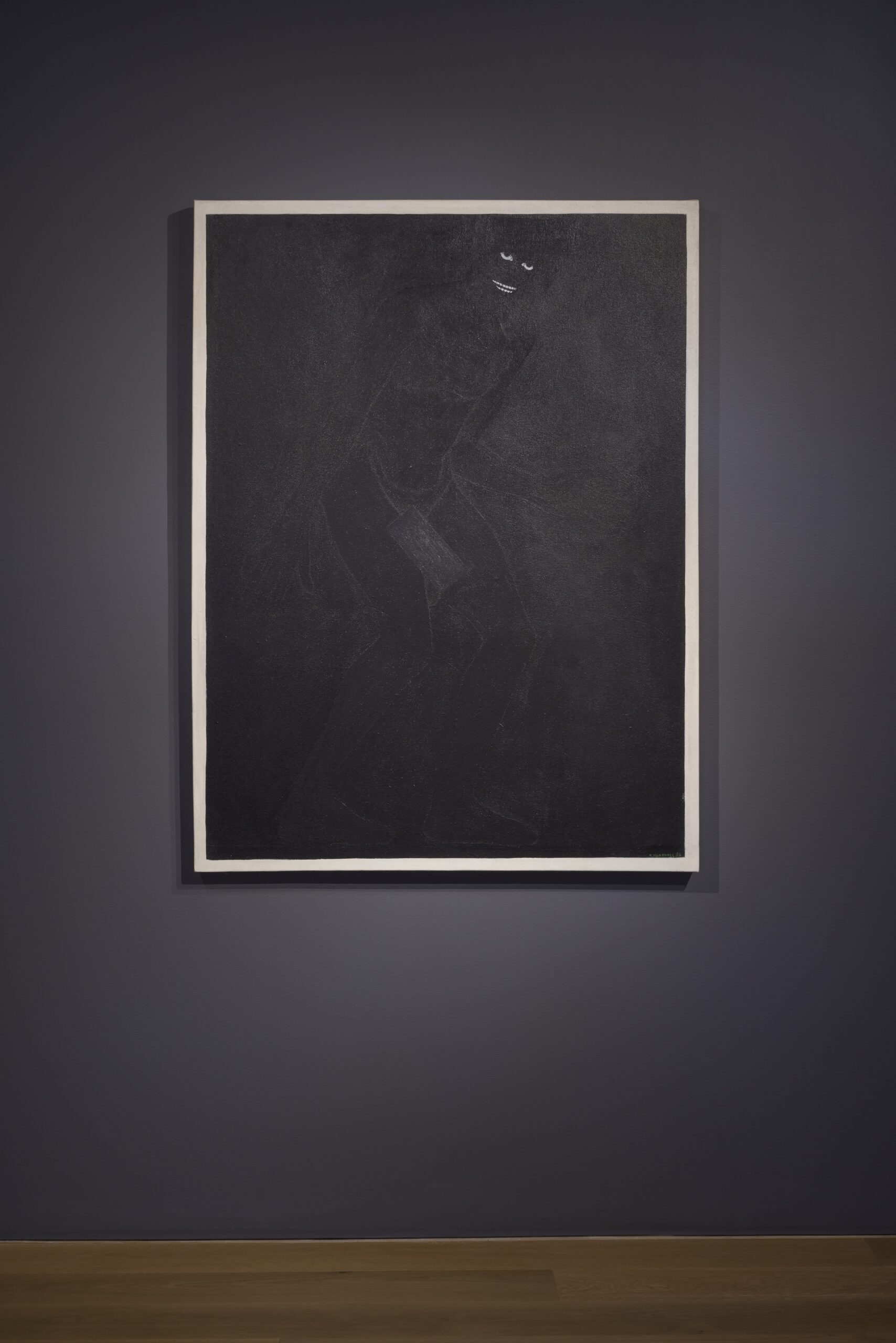

Marshall is a man of perception, but that is to be expected. As a past winner of the MacArthur genius grant, whose art has been featured at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Tate Britain, he cares about how things look. Strolling through the Rennie gallery, where his exhibit “Kerry James Marshall: Collected Works” is on display until Nov. 3, 2018, he points out details most people would be hard-pressed to notice the first time around. As he does, the deeply thoughtful messages he’s trying to convey become a little clearer.

Because while Marshall’s work is intended to provoke thought, it is not intended to provoke just any thought. “I’m not into free association,” he says, laughing again beneath a series of colossal Civil Rights-inspired stamps mounted just above their corresponding—and equally large—ink pads. “Really, I try to put in the things that I want people to think about. I don’t want people to think about just anything they want to think about.”

This attempt to guide and stimulate audiences, often through re-examinations of historical events and the shifting experience of blacks in America, earned him such high-profile fans as Frank Ocean, Beyoncé, Michelle Obama, and P. Diddy, the last of whom recently spent $21.1 million on Marshall’s painting Past Times. The purchase, in May 2018, made Marshall the most expensive living black visual artist in the world, but it was hardly his first success. He’s spent decades crafting art that examines everything from slave ships to Afrofuturism, the Pan-Africa Movement, and the Watts riots—a week-long event that the Los Angeles native actually witnessed firsthand.

It was an experience, he says, that has informed his works in more ways than one. Still standing beneath the giant stamps that use phrases like “Black is Beautiful” and “Burn Baby Burn” to spell out a statement of black affirmation, Marshall talks about how the 1965 race riots in the Watts neighbourhood of LA meant so many things to so many people, but only one thing to him. He was nine years old at the time and living over 70 blocks from the riot epicentre, so his experience was different from nearly everybody else’s. “By the time it got to us,” Marshall says, “it looked like a carnival. People were having fun.”

You can’t tell another person exactly what something means or how it felt, or even know all those things for yourself, Marshall explains. He’s now walking past his next work, a triptych inspired by George S. Schuyler’s Black Empire, a sci-fi novel in which future African-Americans stage a revolution and create their own independent state. The work is beautifully detailed, and shows in vivid etchings black people driving flying cars and picnicking in futuristic cities. There is also a man holding a warhead in his bare hands, standing alone on a pedestal. It’s carefully crafted, and drawn from Marshall’s own experiences, his own thoughts. It’s provocative.

Still, even though he wants us to see specifically what he’s drawn, and to think directly about the ingredients he’s provided within the work, he is not telling us what our opinions on his chosen topics should be. “I’m not trying to tell somebody that this is the way it is,” he says, looking up with everyone else at the work he created. “‘This is something worth thinking about’—that’s what I’m saying.”

Keep up with the Arts.