The Western is the most American of genres, but in the 1970s, as the United States’ idea of itself began to change and art-house cinema reflected the country’s disillusionment with authority, two films with British Columbia connections challenged the Western’s foundational beliefs about morality, violence, and community.

In 1971, West Vancouver became the rainy Washington State town of Presbyterian Church for Robert Altman’s dreamy, seasonal, revisionist Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, the story of a partnership between a small-time gambler (Warren Beatty) and an opium-smoking madam (Julie Christie). Then in 1976, Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales, a violent and picaresque Western Aeneid, featured a supporting role for Chief Dan George, a Tsleil-Waututh actor and entertainer whose role subverted the expectations of an Indigenous sidekick.

In McCabe & Mrs. Miller, “Pudgy” McCabe (Beatty) rides into Presbyterian Church as many Western heroes do, possessing only his horses and a reputation for violence. But McCabe’s reputation is just a useful fiction, helping him establish a brothel. He partners with Mrs. Miller, a cockney businesswoman as sharp and cynical as McCabe is romantic. As the town grows, McCabe scorns an offer from a large business concern, only to regret this when the outfit’s hired guns murder a young cowboy (Keith Carradine). Trapped, McCabe is forced to confront the gunmen while the town’s church burns.

Presbyterian Church is unusual in the history of Western film towns—rain-drenched, evergreen, a muddy patchwork of bridges and walkways. Altman shot the film in sequence as the town was constructed. Keith Carradine says in Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, “The sets for that movie in West Vancouver were up above a housing development.… [Altman] had all these carpenters and craftspeople and artisans from Vancouver that came up to work on the set and build the place.… It was absolutely magical.” Julie Christie reminisced in an interview with Roger Ebert, “Presbyterian Church seems like a real place to the people in the movie because it was a real place for all of us.”

A Leonard Cohen fan, Altman scored the film to several Cohen songs, each cued to a character or sequence: “The Stranger Song” to McCabe, for example. American music writer Robert Christgau wrote that Cohen “dominates the soundtrack of McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” and called the film “as groundbreaking sonically as it is visually.”

Roger Ebert wrote of McCabe, “Death is very final in this Western, because the movie is about life. Most Westerns are about killing and getting killed, which means they’re not about life and death at all.”

A similar sentiment is expressed in The Outlaw Josey Wales by the title character, negotiating peace with the Comanche Chief Ten Bears (Will Sampson): “Dying ain’t so hard for men like you and me. It’s living that’s hard.… men can live together without butchering one another.” Eastwood called Wales “a statement that mankind has to find a better solution than just battling themselves into the ground.”

Of all the Westerns Eastwood starred in and directed, Wales is the most grounded in the bloody, racist history of North America. The source novel, written pseudonymously by a Klansman and segregationist speechwriter, was inspired by the life of Bill Wilson, a Confederate “bushwhacker” who, like Jesse James, refused to surrender after the Civil War. Kaufman and Chernus’ script draws parallels between Reconstruction and the genocide of Indigenous peoples, a dishonest equivalency which allows the characters to find common ground in resistance. Wales forms a surrogate family with Cherokee elder Lone Watie (Chief Dan George), two white settlers (Sondra Locke and Paula Trueman), and a Navajo woman (Geraldine Keams), striking a peace treaty with the Comanches and defending their new home from mercenaries.

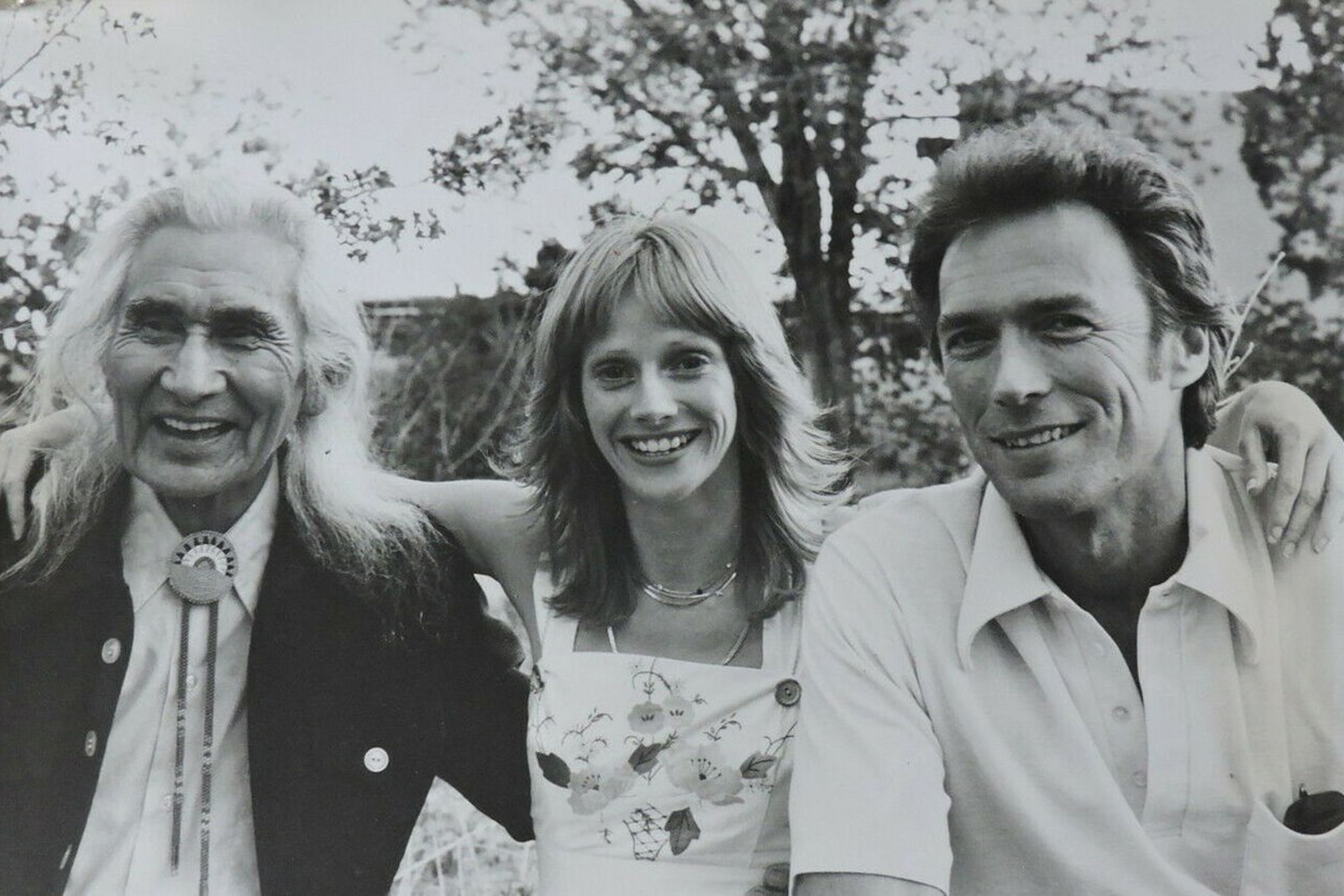

Chief Dan George, born Geswanouth Slahoot and given the name Teswahno, won acclaim for his portrayal of Lone Watie, Wales’s travelling companion, comic foil, romantic rival, and friend. Born on the Tsleil-Waututh reserve near Deep Cove, Slahoot was forced to attend St. Paul’s Indian Residential School in North Vancouver (now St. Thomas Aquinas Secondary) from age five. According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the school was frequently cited for overcrowding, infectious disease, or malnourishment: one official described it as a “death-trap” and “fire-trap.”

George worked as a lumberjack, longshoreman, and hunter before touring with a country-folk band called Chief Dan George and His Indian Entertainers. His breakout roles as an actor were the CBC show Cariboo Country and George Ryga’s play The Ecstasy of Rita Joe. George began working steadily, earning an Oscar nomination for Little Big Man. In an iconic speech marking Canada’s centenary, “Lament for Confederation,” he wrote, “My nation was ignored in your history textbooks.… I was ridiculed in your plays and motion pictures.”

But in The Outlaw Josey Wales, in contrast to stereotypical Indigenous roles, Lone Watie is resourceful, competent, sexually active, and possesses a wry, self-deprecating humour. Describing his humiliation at the hands of the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Watie says, “We told him about how our land had been stolen and our people were dying. When we finished, he shook our hands and said, ‘Endeavour to persevere.’… We thought about it for a long time, ‘Endeavour to persevere.’ And when we had thought about it long enough, we declared war on the Union.”

McCabe & Mrs. Miller and The Outlaw Josey Wales complicated and enriched the Western genre. The fair-fight shootout, the conquering of nature, the subjugation of Indigenous culture, the clean and happy ending with the townsfolk safe—these elements are avoided or subverted. Instead, the films offer strange and complex meditations on community and place. With their connections to British Columbia—a fictitious town built on the slopes of West Vancouver, and a Tsleil-Waututh actor whose opposition to colonial practices matched his role on screen—perhaps this complexity was inevitable.

Read more local Arts stories.