Mark Vonnegut wasn’t the only college-age American heading north to British Columbia in the early 1970s. Hoping to avoid the Vietnam draft and searching for a utopian way of life outside the conformity and materialism of Nixon’s America, he and some fellow expatriates bought land north of Powell River and established a communal farm. After a few months, though, he began to suffer a severe mental illness that would lead to two stays in a psychiatric clinic in New Westminster. The Eden Express, published 50 years ago, is his first-hand account of his illness and treatment, and it serves as an outsider’s look at B.C. during a momentous cultural shift.

Mark Vonnegut was born in 1947, the eldest child of Kurt and Jane Vonnegut. Raised on Cape Cod, Mark studied religion at Swarthmore College, registering as a conscientious objector and working as head of security at a psychiatric hospital. In 1969, the year Mark graduated, his parents’ marriage was nearing its end, and Kurt’s literary fortunes were rising with the publication of his landmark novel Slaughterhouse-Five. He and his girlfriend (known as Virginia in the book) set out for B.C. to buy land. Given the cultural clashes of the late ’60s and early ’70s, “leaving the insane society to set up an independent self-sufficient commune seemed like a very sensible noble brave thing to do.”

The trip west wasn’t without incident. Vonnegut was arrested for drug possession in Pennsylvania and released pending trial. Hearing “tales of people being hassled by Canadian immigration on the West Coast,” he and Virginia took a detour to cross into Canada via North Dakota. In the summer of 1970, they drove the Trans-Canada Highway, camped out in the Rockies, and stopped at Cultus Lake, “one of the loveliest places we had stayed.” They met other Americans with similar goals of freedom and a return to nature, who believed Vancouver was “a cosmic magnet drawing us all there.”

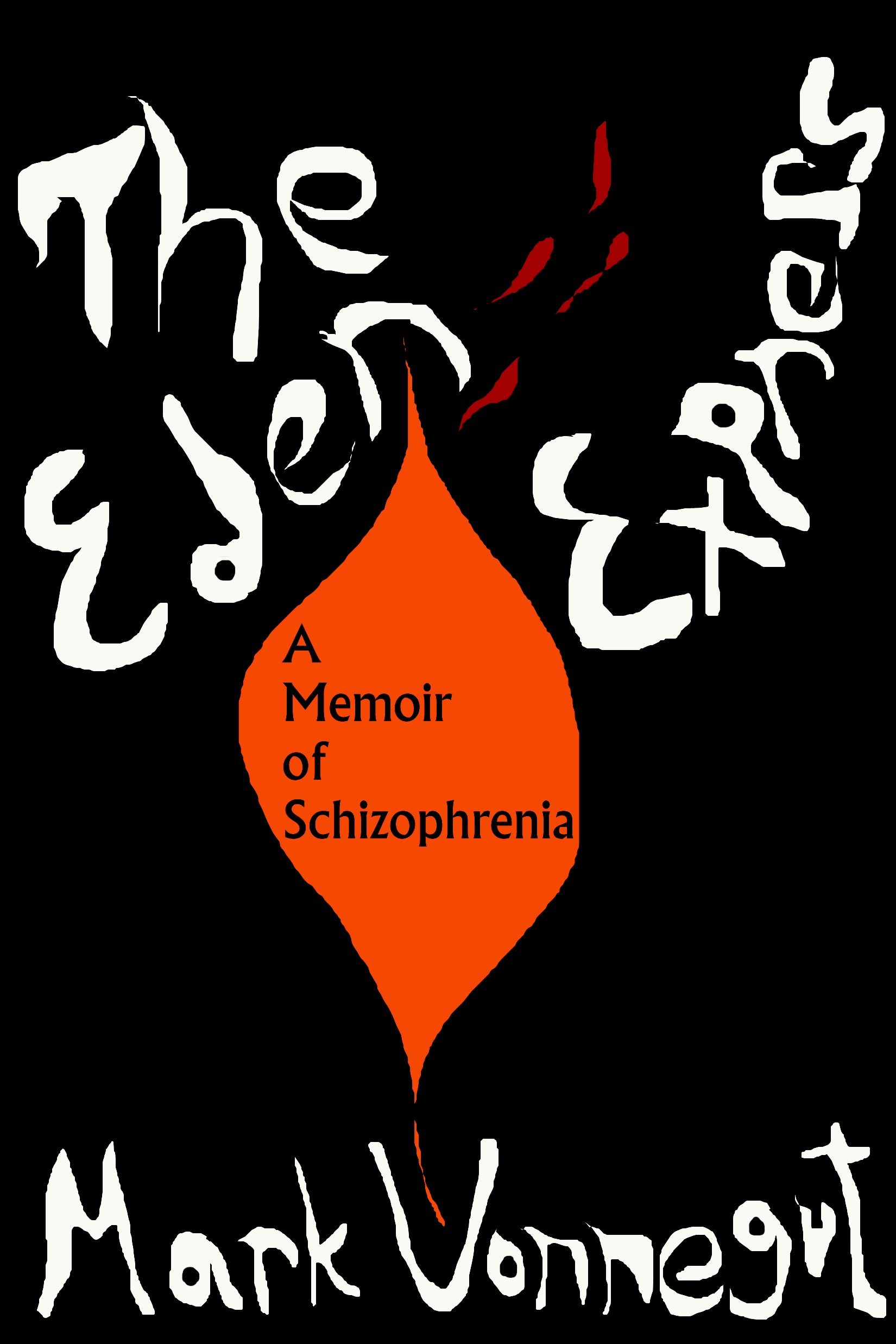

2002 edition of The Eden Express. Courtesy of Seven Stories Press.

Mark’s impressions of Vancouver at the time could just as easily have been written in 2025: “Apartments were pretty expensive and the job situation was dismal.” He began to focus on the Sunshine Coast. The group bought an 80-acre tract about 15 kilometres north of Powell River, only accessible by boat and logging trail. While this land is part of the traditional territory of the Tla’amin Nation, to Mark and the other Americans it seemed a “virgin frontier, unspoiled except for ugly scars left by loggers here and there.”

The farm’s new occupants spent their first days repairing and reroofing the dilapidated structures. The group was enthusiastic but inexperienced, drawing help from the Sunshine Coast locals for transportation, equipment maintenance, and general advice on roughing it: “the sort of life we aspired to wasn’t that far removed from their own…. Many of them had spent their childhoods in the bush. We struck a chord.”

Mark found life on the farm both rigorous and ideal. He helped plant crops, made infrequent trips to town, and even bought a pair of pregnant goats. Yet a series of bad drug trips and his girlfriend’s admission of infidelity seemed to precipitate a change. He began to have apocalyptic visions, sometimes having long discussions with people who weren’t there. Sleeping and eating became difficult. His friends worried for him.

“My son, Mark, has had a nervous breakdown, and has been diagnosed as a schizophrenic,” Kurt Vonnegut wrote to a friend in June 1971. Mark would, in his father’s words, “wing a cue ball through a picture window in an urban commune in Vancouver…. Mark and I went in a hired car from the house with the broken picture window in Vancouver to what turned out to be an excellent private mental hospital in nearby New Westminster.” On Valentine’s Day 1971, Mark’s family and friends committed him to Hollywood Hospital, a private psychiatric clinic where celebrities such as Cary Grant and Ethel Kennedy had stayed (and which had become, as Jesse Donaldson writes, “known nationwide for its pioneering work in the controversial field of psychedelic therapy).” Mark’s treatment involved milkshakes laced with heavy doses of Thorazine. After a short while, he convinced one of the doctors he was well enough to leave.

Back at the farm, the cycle repeated. Ravings and suicide attempts became frequent. Committed involuntarily this time, Mark was given a radical treatment of vitamins to address the chemical imbalances in his body, as well as Thorazine and shock treatment. While some of these techniques have since been discontinued, the doctors’ treatment of mental illness as a biological issue was ahead of its time: “It took quite a bit to convince us that anything as pedestrian as biochemistry was relevant to something as profound and poetic as what I was going through,” Mark writes in The Eden Express. In fact, his condition wasn’t schizophrenia but bipolar disorder, and Mark would change his mind about the vitamin regimen’s effectiveness. Yet with biochemical treatment, his condition improved.

First published in 1975, The Eden Express garnered solid reviews. The New York Times Book Review called it “a searchingly vivid, if sometimes voluble account of the inside of a schizophrenic breakdown, the struggle to recover, to understand.” Insisting that he didn’t offer advice to his son about writing the book, Kurt Vonnegut called it “perfectly wonderful” and “important,” and wrote the foreword to the 2002 edition.

Mark Vonnegut, photographed by Sean Goss. Courtesy of Seven Stories Press.

Mark would go on to graduate from Harvard Medical School, becoming a celebrated pediatrician and author. In 2022, he published The Heart of Caring: A Life in Pediatrics, another autobiographical book, this time tracking lessons from his more than 40 years in medicine.

Now celebrating its 50th anniversary, The Eden Express chronicles the sojourn of a literary icon’s son in a vanished British Columbia of frontier living, hippies, and doctors on the verge of a revolution in how mental illness is diagnosed and treated. As Mark Vonnegut writes in the introduction to the 2002 edition, “Looking at mental health problems the same way we look at other medical problems is factually correct—the best bet for reducing the disabling symptoms and the only way to lessen the stigma and blame that traditionally double or triple the pain.”

Read more stories about art in B.C.