The only way through was to write. It was the only way to process the loss and the ensuing disorienting grief—the only way to face it completely.

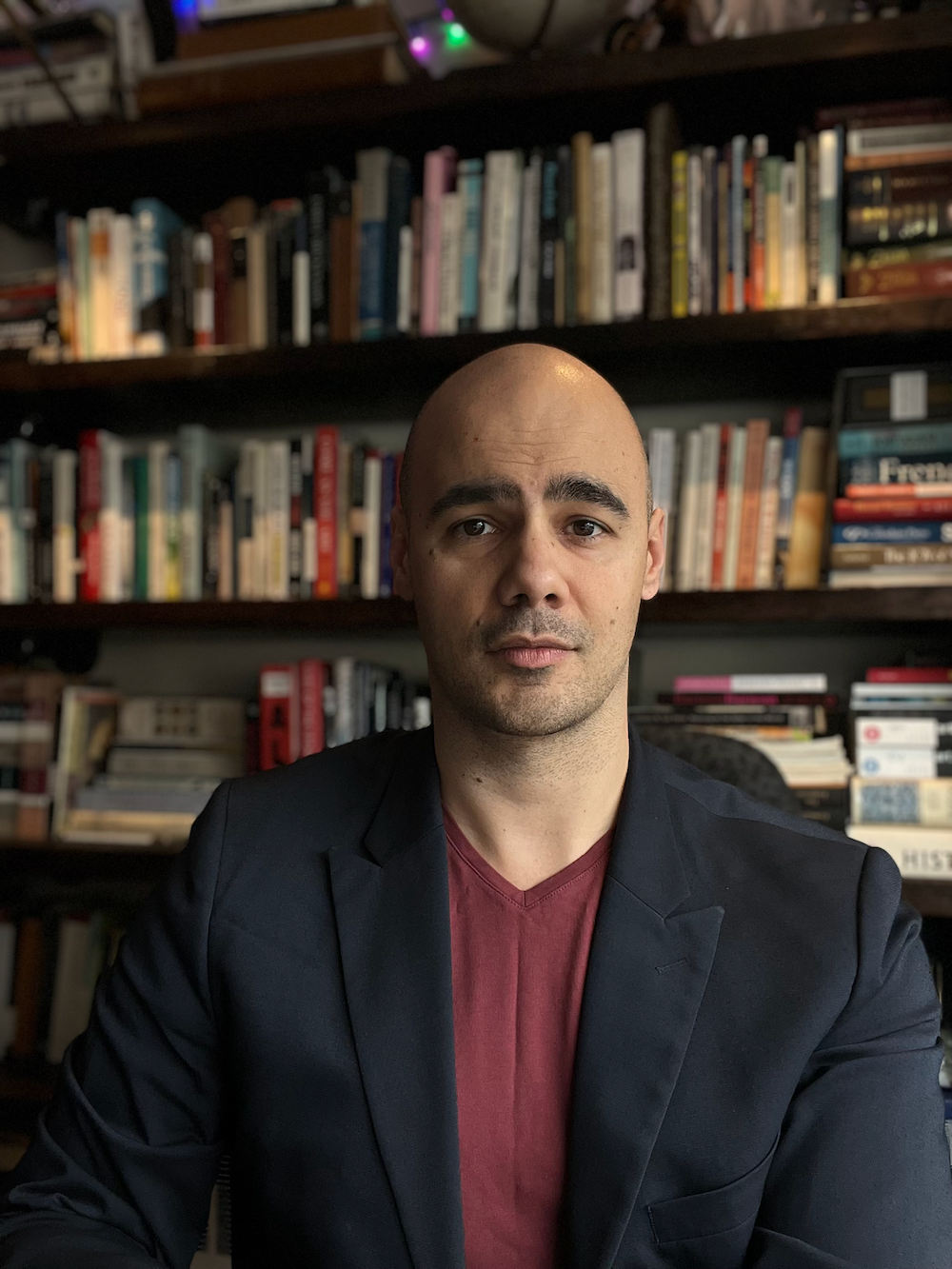

Despite the numbness that blurred out the days around when his father passed away, Miguel Eichelberger remembers that part clearly: “Whatever comes next, whatever I’m feeling—doesn’t matter what—I want to stare nakedly at it, and I want to understand it,” he thought. A week after writing the inscription on the inside cover of his father’s funeral program, he began. He wrote constantly for the next two years.

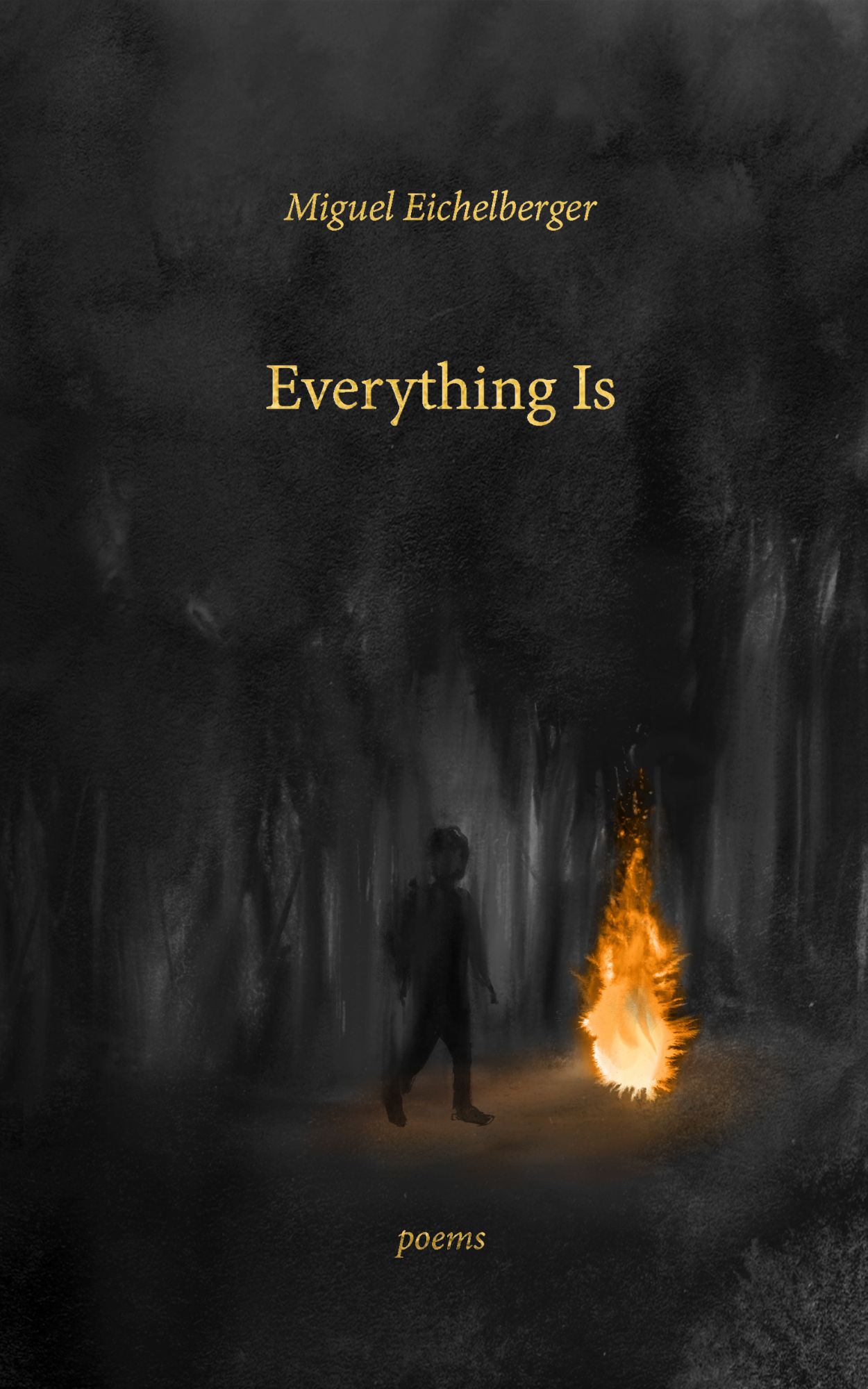

Eichelberger’s debut collection of poems, Everything Is, is the result. With clarity, intimacy, and grace, he navigates the process from hospital room to hindsight, acknowledging the emptiness and hard edge that well-meaning platitudes seek to fill and soften. What Eichelberger reveals through his own experience is something heartbreaking, beautiful, and human. Grief, it turns out, is not something to fear.

“This is such a human thing,” he says, speaking from his home in Vancouver. “It’s not something to fear.”

Eichelberger’s creative work has been published in literary magazines and performed on stages including at the Vancouver Fringe Festival and Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Born and raised in Northern B.C., he studied theatre and archeology—the latter an apt concentration considering the emotional excavation at the heart of his work—at the University of Calgary. Poetry quickly became the thing. He “ran” to it when he was about 20—easier, Eichelberger thought at the time, to hide in a space that was more open to interpretation than fictional prose could be. But as he fell in love with the form and craft and immersed himself in the greats—specifically “magic” Leonard Cohen, whom Eichelberger credits for teaching him “what you can do with simplicity”—he found that poetry articulated what there are sometimes no words for.

“For me, to get through things, I need to try and give it language,” he explains. “If I can give it language, that’s a lever that I can hold onto, or that I can pull, or I can even carry for a little bit until I’ve understood it fully, and then I can put it down. That’s why it can’t be prose—it needs to be in this other weird space that you have to think your way into and feel your way into. And you might not come up with something that makes a whole lot of sense—but it does somehow, right?”

His father was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1985, when Eichelberger was two. He was told that the cancer he had had a 90 per cent mortality rate at the time; only one in 10 people survived. “He apparently calmly said from that diagnosis space, ‘Okay. I’ll be that one.’ That was it. And that’s how he met everything,” Eichelberger says.

He beat it, and the family had over 30 more years with him. Eichelberger had a very close relationship with his father, his role model in everything and “quite literally the best man I ever knew”—a person, Eichelberger describes as having led “with self-respect, with respect for others and respect for nature and respect for all of the sundry experiences that we go through as human beings, including death, life, love, all of it.”

Eichelberger continues: “He looked upon almost everything, including suffering, with a sense of adventure. And so that was always everything to me.” Eichelberger remembers the walks they took together on the farm, tucked between Dawson Creek and Fort St. John, where he grew up, when his father would make sure his son understood the importance of listening, being present, and staying curious. “He’s the reason that I even knew to face grief,” Eichelberger adds.

In Everything Is, he faces it with honesty and self-compassion. What he had to face after getting the call and learning the news. That one detail that stood out at the wake. Sleep, finally, and the loneliness and the going through the motions. “I pick up the phone to chat about it, and put it down when I remember,” he writes in “On What Loss Might Be For.”

One of the most affecting things about the work is Eichelberger’s style. “Watching Mourners (sung to the tune of One of Us Cannot Be Wrong by Leonard Cohen)” honours both his literary hero and affinity for rhyming poetry. The words sway to the melody, some lines pairing perfectly with certain lyrics, in a subtle yet powerful exercise. It was a way to sneak a rhyming poem in, he admits—a form he believes too often gets looked down upon—and present it in a way that actively engages the reader with rhythm. “Anything that I write moves to music, even if you can’t hear it,” he says.

And then there’s the blank space that follows the last line of “At a Body’s Bedside.” When in the hospital room with his father, Eichelberger recalls the overwhelming quiet, how he talked and cried but heard nothing in return. He thought about those nice things people tell you—“the best anyone who loves you can do”—but that ultimately are worthless in the moment. “It’s a thing that you can only do on your own, and you have to do it in that silence,” he points out, “and that’s sort of the truth of what comes next. You’re like, oh—I have to fill the silence now.”

Sometime later, as he began to resurface on the other side, Eichelberger discovered that he received an understanding from his experience with grief, something profound that he considers to be a gift. It’s in the book’s title.

“The huge, absurd catastrophe that is human existence and all of its incumbent beauties and connections and relationships, it’s all good,” he says. “It’s part of it, everything is, and it’s all okay. And that’s what it was for me, going through everything. Even the times where I was ridiculously angry or if I was frustrated or if something that had no connection to my father whatsoever would all of a sudden click and I’d start to cry—it’s all good.”

Loss is devastating. But grief? That’s where there’s room to learn, in that raw, real part deep inside yourself, hopefully with as little self-judgement as possible. It’s really hard— the writing helped him arrive at this place, of course, from the poems to private journals he kept—“if you don’t unpack the stuff, it’s hard to make sense of something if you don’t see its pieces”—but so did his father. His constant encouragement to listen, be present, stay curious.

“My dad never wanted me to be anything but me,” he says.

He hopes his work can do the same for others. That this collection of poems can be a companion of sorts through grief—any kind of grief, something every single person goes through—that sees all the complicated turns of the road. Among the dedications to the book, which includes Eichelberger’s father, Max, is the reader.

“I say this with all the love in the world: I hope it invites you to hurt. I hope that invites you to feel every bit of it. The joy, the love, every hell of it, I hope it invites and helps you. I hope you treat it as a thing that’s kind of holding your hand a little bit along the way. I’ve never really been an art for art’s sake kind of person. Art has utility, it has use, it has meaning. And that’s what this is for.”

Read more stories about poetry.