It was Canadian singer-songwriter Ferron who best expressed both the imperiled state of the 2023 Vancouver Folk Music Festival and the precious fragility of life, yoking the two together at the end of her July 15 set.

It was at the least-shaded stage, the west one, at the farthest end of the festival grounds; the midday sun was cooking, and the 71-year-old folk icon had wished aloud that she could erect a protective umbrella over all of us. But the bug-under-a-magnifying-glass glare was not enough to deter her diehard fans from cheering on songs like “Misty Mountain” or singing along to the title track of 1980’s Testimony (“I never need to be alone on this song,” Ferron had observed; and so she was not).

Maybe some of the people sitting on blankets in front of the stage had seen her back in 1979, when she first performed at the festival, then in its second year, or at the 1980 event; the festival guide lists her as the “only veteran” of those early years returning for 2023.

And so her final remark—as best I can remember it—had a power borne by her depth of experience and the immediacy of hearing her in person: “We may not be here together again, but we were here today.”

Ferron was the local legend I was most excited to catch at the festival, but she was not, all told, the person who made the strongest impression. It’s always those you don’t know who blow you away the most. Last year, it was Allison Russell (returning for a free show this August for Burnaby Blues and Roots); this year, it was Russell’s friend and sometimes collaborator Amythyst Kiah.

I wasn’t alone in being impressed by Kiah. Everyone seeing me in her shirt on Saturday told me how great her Friday night main stage show had been, including a random fellow named Michael on the number four bus on Saturday night, who opined that she had the strongest voice of anyone at the festival. Neptoon Records’ Ben Frith, managing the merch area, said that Kiah had kicked ass in both CD and T-shirt sales.

“The merch here is unusual,” Frith explained to me. “CDs sell first”—all of Kiah’s went—“then vinyl, then knick-knacks, with T-shirts a distant last.”

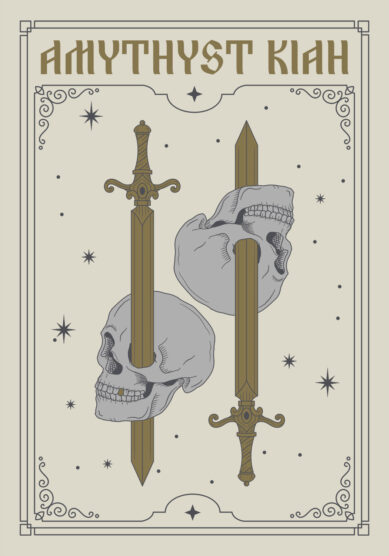

Frith chalked up Kiah’s shirt-sale success to “great design.”

I was able to ask Kiah about the image on one shirt, which riffs on the Two of Swords tarot card. “The guy that did the artwork, his name’s Flo Mihr,” she told me. “He did the album art, with that photograph, on my 2021 Wary + Strange album, and he’s also done all of the designs for all of my T-shirts since Wary + Strange,” with Kiah suggesting elements and Mihr realizing them.

Artwork by Florian Mihr.

Kiah sees tarot as a way to “visualize your life in symbolism… With the swords and the skulls, it represented a kind of rebirth and change that I am personally going through, which I think is something that happens throughout our lives, a kind of death and rebirth. Sometimes you have a sense of purpose, but then that changes and you have to re-find it again, and rebuild how you think of yourself.”

I also asked Kiah about what was surely the most confrontational lyrical image in any song in the festival, in “Black Myself.” While some bands shied away from direct political confrontation, Kiah went straight for the throat with her lyrics: “Is you washed in the blood of your chattel? / ’Cause the lamb’s rotted away.”

Surely that image provoked some reactions?

“I’ve not had anybody confront me directly,” she said, smiling. “But I absolutely can see someone reading that line out of context and feeling strongly about it. But I’m talking about a very specific idea, that the people who were enslaving other people, a lot of them claimed to be Christian, and would even have church services on the plantation. There was something called The Slave Bible, where they edited it so there were only the verses about obeying your master! So it’s hypocrisy. My idea, with ‘the blood of the lamb’s rotted away,’ was that you’re killing the whole idea of what it means of being a spiritual, kind, benevolent person, which is what I’ve at least heard is what Christianity is supposed to be about! And there are plenty of people who exhibit that, so it’s not a dig at Christianity as a whole.”

Her complex grappling with Christianity was echoed by the artist I was second-most excited to see at the festival, Indigenous country singer William Prince, at the “Let the Spirit Move You” workshop, a gospel-themed set held, appropriately enough, at 11 a.m. on a Sunday. He performed alongside host Jim Byrnes, Black vocal group the Sojourners, instrumentalist Maya de Vitry, and vocalist Krystle Dos Santos, who sang a couple of somewhat overdone songs (“Amazing Grace” and “Hallelujah”) before winning me back with a song dating to the days of slavery, “Wade in the Water,” first recorded in 1925.

William Prince.

When his turn came around, Prince, a natural storyteller, noted the “Every Child Matters” shirts in the crowd and observed that “it hasn’t always been easy for my people, going to church. A lot of work, unfortunately, was done to change a lot of my people, to extinguish. I’ve reconciled myself with that in my own way,” he said, but he still values “the feeling” of gospel music and remains, apparently, a man of faith.

Two of his three songs were from his 2020 album Gospel First Nation, beginning with the title track; his third song, “Great Wide Open,” was from his 2020 album Reliever and was written as part of his “reconciling with the death of [his] father.”

The smaller afternoon stages are where the most intimate and moving performances are had, though occasionally someone takes the main stage who performs with such passion that even the most distant attendee feels the power. Such was the case with Joachim Cooder’s cover of the Grateful Dead’s “Ripple,” during the American Beauties Dead tribute on Saturday night, which made me regret missing his main performance. Viewed from behind a sea of practised festival lifers who yearly descend to blanket the field in front of the main stage with tarps, blankets, and little folding chairs, he was only a pinprick in the distance as he sang, but he still sent chills up my spine.

That Dead cover set was surprisingly great. Jim Byrnes gave a rollicking, energetic reading on “Turn On Your Love Light,” surely the most show-tunesy tune in the Dead’s catalogue, for which his gravelly bluesman’s voice was a fine match; Kiah offered “Tennessee Jed,” befitting her home state; and Rich Hope was the perfect man to deliver “Truckin’.” Hope’s ripping cover of the Flamin’ Groovies’ “Golden Clouds” earlier on Saturday afternoon had been another high point of the festival (some of the live footage in his weirdly occult video was shot by me on my cellphone and edited into the video by one-time Hope sideman and MONTECRISTO writer Adrian Mack).

Alas, my wife’s camp chair broke during that song, and—frazzled by a long day of sun, lines, and walking—she gave up; walking her back to her distant car, broken camp chair in tow, I missed out on most of Hope and a few more bands besides. I got back in time for the main stage set by Prince, who promptly reminded me of my wife’s absence with songs like “When You Miss Someone” and the sublime John Prine–influenced “Easier and Harder”—a profound little number about marriage—both off his newest album, 2023’s Stand in the Joy. He introduced the song by commenting that he hoped we were sitting next to someone we loved. I felt a stab of loneliness, then went and bought three of his albums at the merch tent.

William Prince with Jim Byrnes.

But Prince’s most moving observation took place the next morning at the gospel stage. I had convinced my wife to accompany me back to the festival and persuaded the volunteers to let her come in again, to compensate for her camp-chair ordeal, so she could see at least a bit of Prince, who was the reason I’d bought her a ticket in the first place. I was glad she was there when Prince looked over at Byrnes and observed, “You know, it’s funny, Jim, my dad had beautiful white hair just like you, and would play a Telecaster just like that. Just the way you’re sitting here, it’s probably the closest…” And then he trailed off, choking up a little, drawing supportive applause from the seated audience.

Maybe he’s one of those “men who easily cry,” as Ferron puts it, but it was another one of those powerfully restorative moments in a festival that, while imperfect, is an integral, healing, and essential part of Vancouver’s culture.

Here’s hoping that Ferron’s worry that we might never gather there again is simply flat-out wrong.