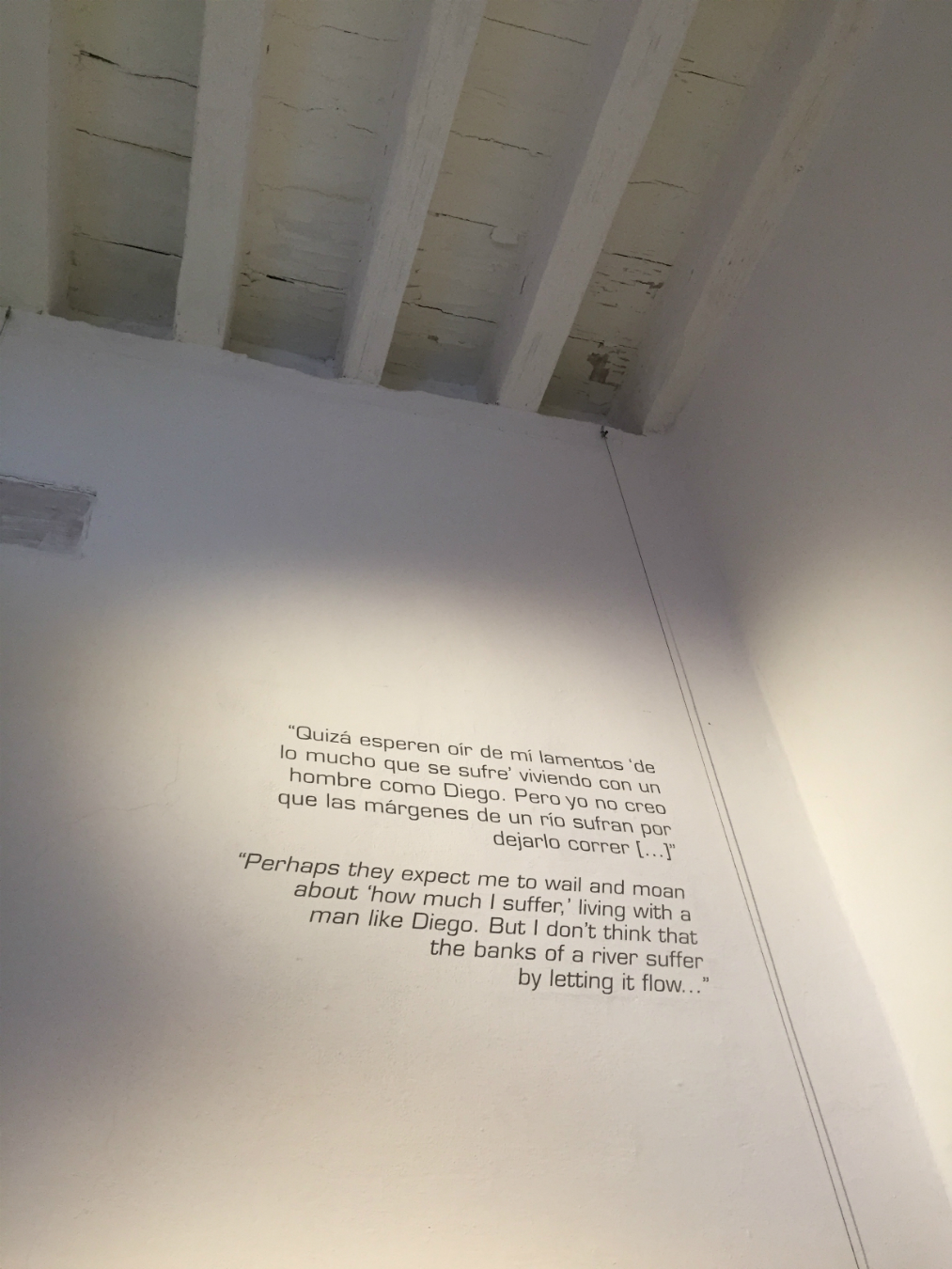

“Perhaps they expect me to wail and moan about ‘how much I suffer,’ living with a man like Diego. But I don’t think that the banks of a river suffer by letting it flow…”

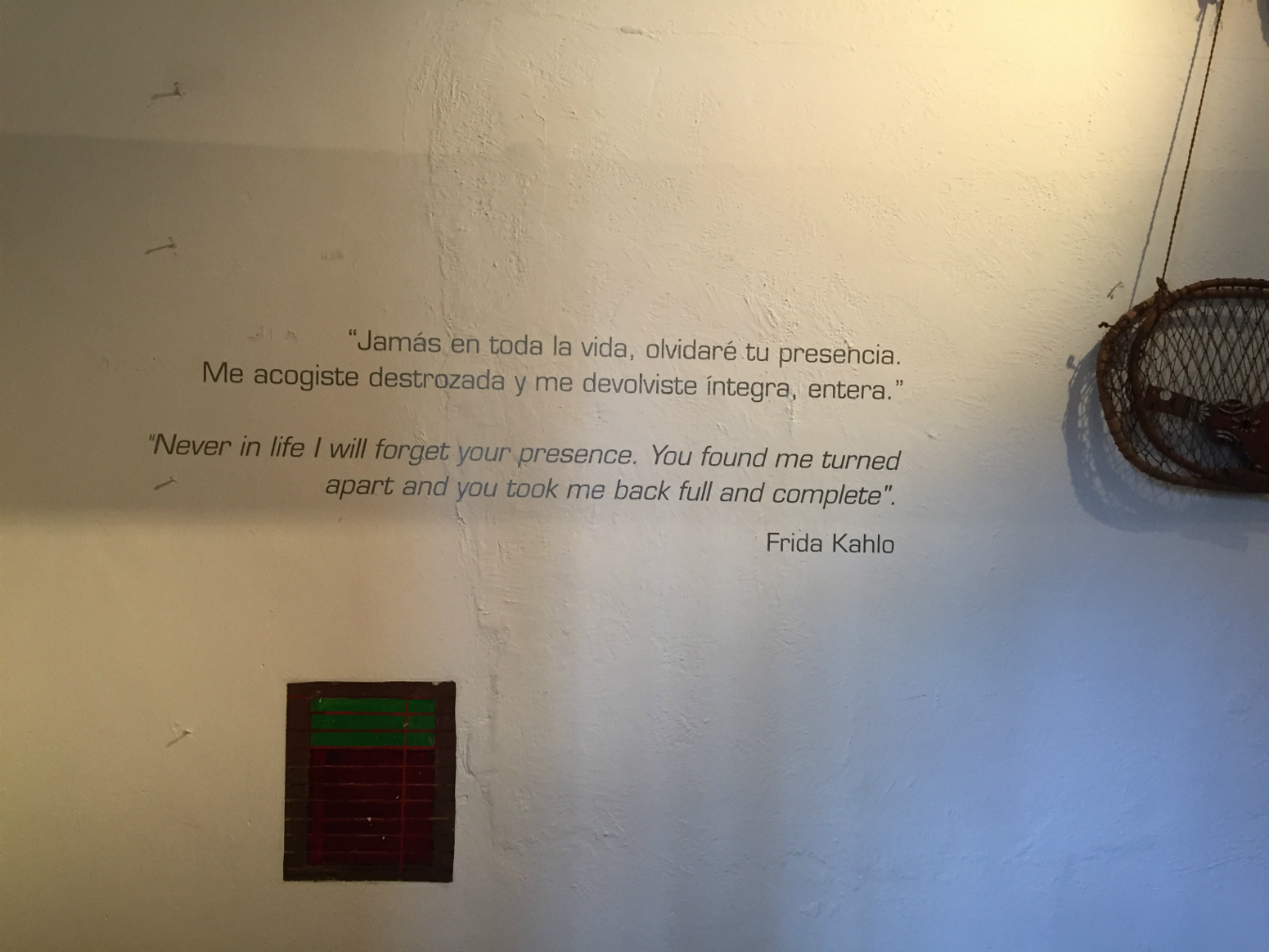

The words, painted in both Spanish and English, adorn one of the many walls inside la Casa Azul (the Blue House), where iconic Mexican artist Frida Kahlo lived and died. Now turned into a museum, Museo Frida Kahlo, the bright blue home is a treasure chest of history—and one of Mexico City’s many celebrations of the trailblazing painter. (It is seemingly always busy, so avoid the line by purchasing tickets for a specific entrance time in advance.)

Built by Kahlo’s father three years before her birth, Casa Azul was not just a part of the artist’s childhood—it is where she remained living as an adult; where she created her work; where she made a life with husband Diego Rivera; where the couple entertained fellow members of the Communist Party; where Leon Trotsky hid out while in exile from Russia. The home tells the story of Kahlo’s passionate, turbulent, and vivid life—it’s there in the walls, on the creaking floors. Displaying a mixture of artworks and artifacts, the museum portrays the spirit of a rebellious woman who was widely cherished and yet misunderstood.

Born in 1907, Kahlo turned to painting as an outlet when a car accident at age 18 left her recovering in a body cast. Many surgeries, combined with the polio she suffered in her childhood, left her disfigured, insecure, and in search of self-definition. Her art was her microphone and her magic wand, allowing her to portray herself however she wanted, to communicate the versions of herself she felt like putting forward. Often, that meant the painfully honest fragments of her troubles, be they regarding her body or her love life.

Kahlo’s physical appearance, a major point of insecurity for her, became part of her character: adopting the Tehuana style of dress, she employed the now-famous hairstyle of braids and flowers, the layers of jewellery, the loose blouse covered in strips of fabric, the long skirt with a ruffle. In an exhibit within the museum, “Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Frida Kahlo’s Wardrobe,” visitors learn about the ways she edited herself to draw attention to her upper body, thus hiding the parts she felt ashamed of. In tandem, the aesthetic became her calling card, her essence: it helped her stand out as a female artist, especially against her famous muralist husband Rivera (it is also said that he loved the Tehuana costume, so Kahlo may have partly assumed it to appeal to him).

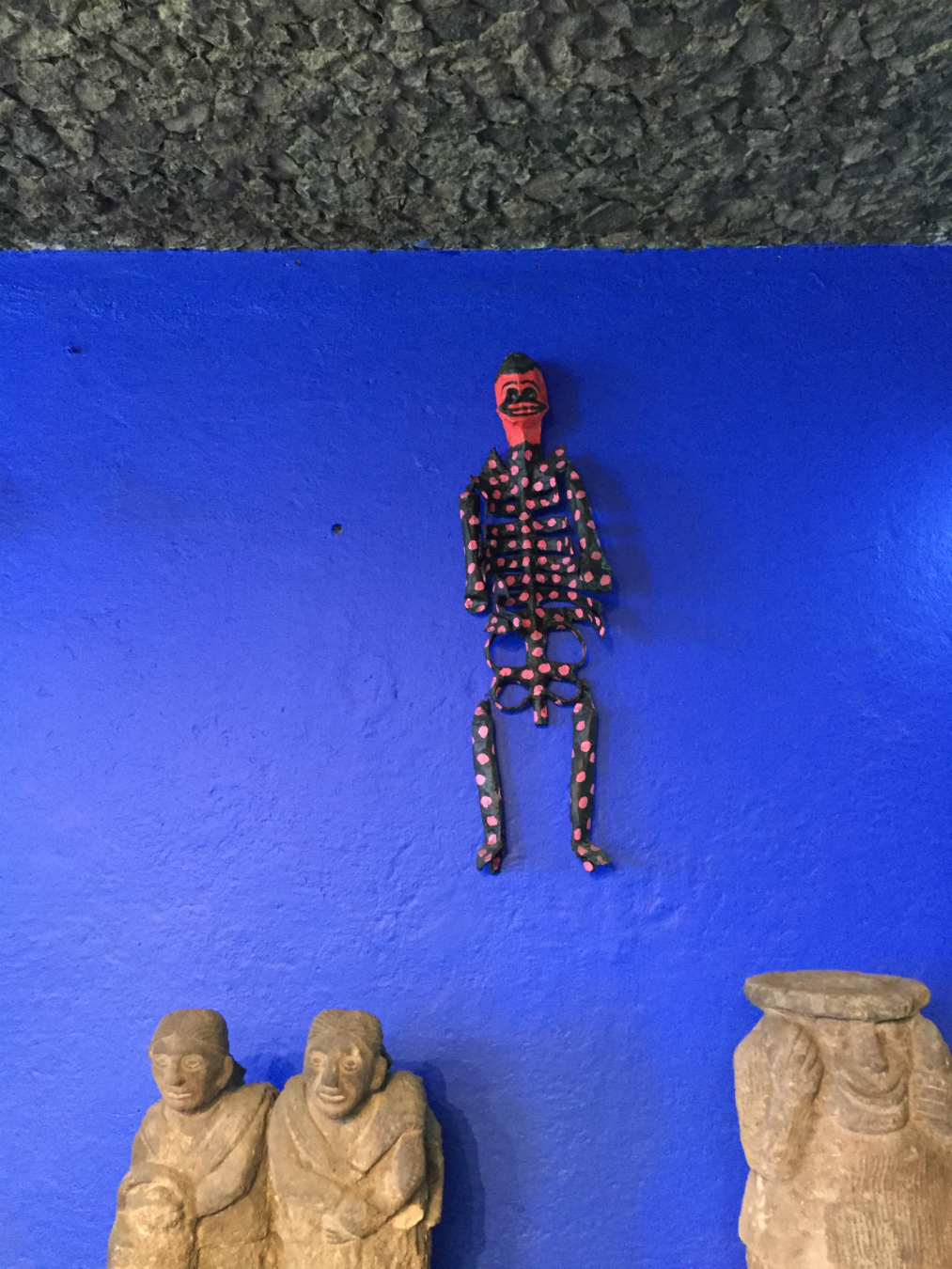

The tumultuous relationship between the two artists is widely documented, from the extensive infidelity, to their inability to conceive a child (due to ailments caused by Kahlo’s many health issues), to their eventual divorce and quick remarriage. At Casa Azul, both Kahlo’s and Rivera’s works are on display, from her self-portraits and still lifes on the walls, to his sculptures in the lush and quiet inner courtyard. Back inside the modest house, trinkets reveal intimate details of Kahlo’s personality: the yellow and blue ceramics and dishes; the pot of paintbrushes and tray of paint; the massive collection of books; the dolls and sculptures; the short wooden chair painted with a name, just one: “Frida.”

More from our Arts section.