A little over a decade ago, Vancouver visual artist Lam Wong visited the Louvre to see Johannes Vermeer’s “The Lacemaker,” a painting that Pierre-Auguste Renoir considered the most beautiful in the world. “I kind of agree,” Wong says.

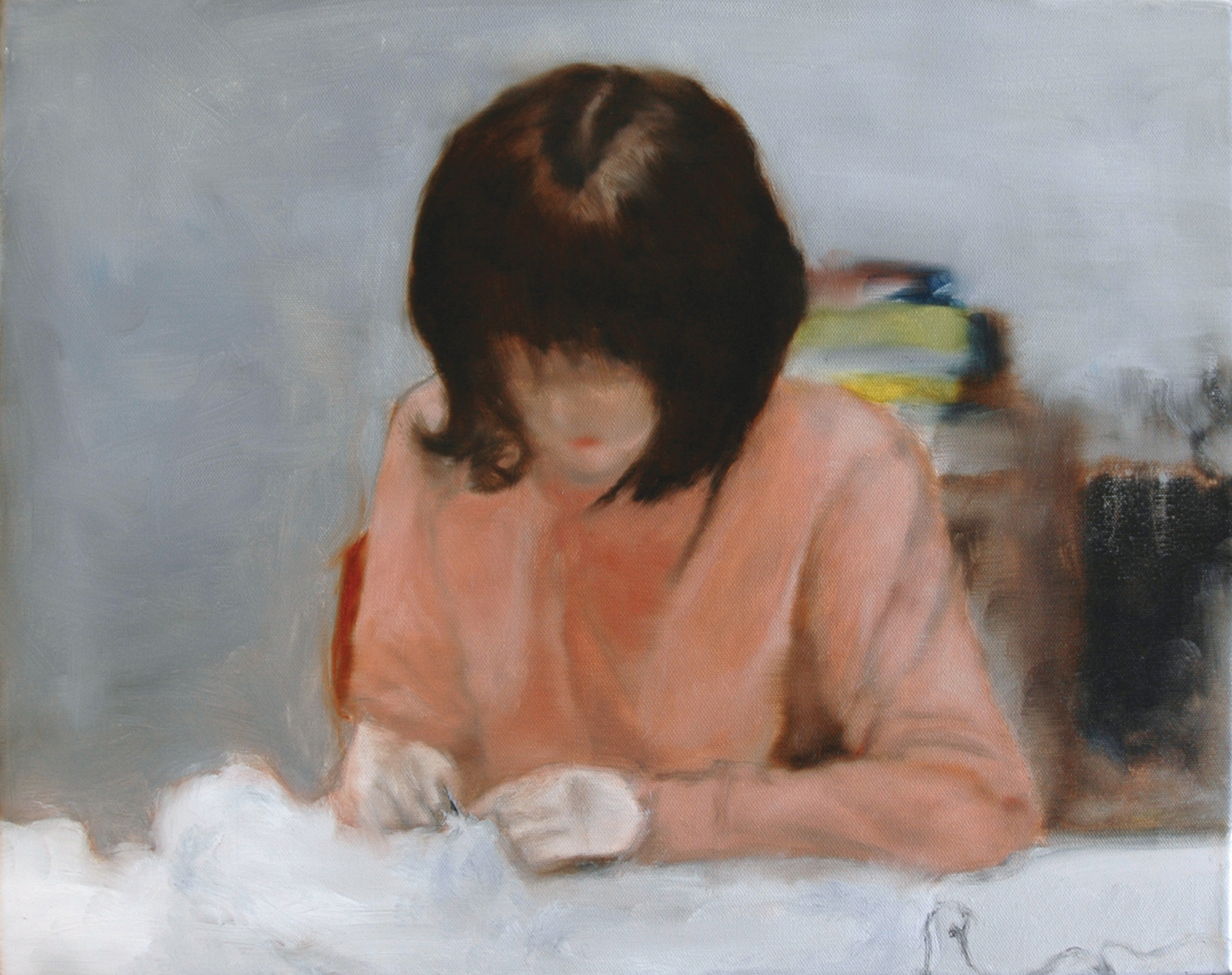

On the day Wong and his wife, Mei, visited the famous art museum, its Dutch room was closed for a special event. Disappointed, they took a seat in the museum’s cafe. “Mei was looking at the menu this time, and then her gesture, her pose reminded me of the painting,” Wong says. In 2011, he turned the moment into a painting of his own.

Even for a longtime VanDusen annual passholder like me, the garden’s little library, down a corridor opposite the main entrance, is easy to miss. This classroom-sized space, shelved with books on flora and insects, currently hosts a small solo show called Mei, titled after Wong’s wife. “The Lacemaker I (at the Louvre)” is a central image in the collection.

The Lacemaker I (at the Louvre), 2011. Lam Wong. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in.

Wong explains that the show, which consists of paintings, drawings, photography, and digital art, is meant to evoke gardens and home life as a sanctuary from the losses of family members, pets, and mentors. “2022 was a heavy year, and we were just so happy it was over,” he reflects. “Having a show in the garden, more about love, and in a celebratory nature, is a good thing.”

Among the reasons I’ve found Wong’s work so fascinating and emotionally compelling, ever since I stumbled across it last fall in the basement of the Sun Wah Centre in Chinatown, are the many dualities juxtaposed in his work: Eastern and Western influences, intimacy and abstraction, surface and subtext, art and audience.

The Lacemaker. Johannes Vermeer. Created circa 1669-1671. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Nothing encapsulates this quality better than my favourite painting of Wong’s, “Westcoast (MOA),” a diptych that depicts two Buddhist monks chatting casually on a bench at the Museum of Anthropology next to a gay couple whose attention is directed elsewhere.

In this image and elsewhere in Wong’s work, the art-goer is the subject and the museum is both a sacred space and a commons. As well, “Westcoast (MOA)” might be the most quintessentially Vancouver image I’ve ever seen.

In Mei are drawings of Wong and Mei’s cats, along with paintings of the camellia sinensis trees that Wong purchased over a decade ago from a VanDusen nursery sale, the leaves of which he now uses to make tea. (Wong comes from a family of tea-makers, and tea has served as the subject of several of his exhibitions and of his documentary film called Tea Zen.)

Wong’s previous work reveals an engagement with history and current events that’s both conceptually textured and emotionally charged. His exhibition last year, Ghosts from Underground Love, was primarily composed of two series of portraits of young women, separated by culture and time but bound by oppression and life under surveillance. (The show was pointedly dedicated to his transgender daughter, eva.) The first set included portraits of Belgian reformatory girls in the early 1900s. Beside each portrait was a hand-painted reproduction of a letter of forbidden love written by them. “I hate all my tortures,” one of the letters read. “They have deprived me of everything: freedom, family, joy.”

Camellia Sinensis I, 2015. Lam Wong. Acrylic and oil on board, 16 x 10 in.

The second set featured the faces of young women from contemporary Hong Kong. Beside each headshot was an abstract hazy grey smear meant to evoke the covered-up pro-democracy graffiti once found in the city. When questioned, Wong pushes back on the idea that this cross-cultural exploration of the oppression of women is political. “My concern is of suffering, not of ideology,” he insists. “I don’t deal with identity politics, or very little.”

Like seemingly all Vancouverites these days, Wong was born elsewhere—in his case, Fujian in 1968, during China’s Cultural Revolution—to parents who worked as musicians. He remembers food rationing and teachers sobbing at the news of CCP leader Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. An early visit to the studio of a friend’s older brother convinced Wong that he was destined to be an artist. “I remember vividly,” he says, “that it was like a paradise for me.”

Wong moved with his family to Hong Kong when he was nine, at a time when emigration from China to the then-British colony was difficult. It was there he first developed a taste for British art rock and design.

Artist Lam Wong. Photo by Roy Hoh.

As a young adult, he moved with his family to Edmonton in 1987. A year after his arrival, he fell ill with tuberculosis and was quarantined at the University of Alberta Hospital. “I was so sick I thought I would die,” he recalls. “I thought before I died, I had to make sense of what life was all about.” It was then that Wong, who was raised Christian, took a greater interest in spirituality—especially the fourth-century-BC Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi. This concern with spiritual matters permeates all of Wong’s work. “Underground Love,” for instance, an installation built around the basement-level elevator entrance at the Sun Wah Centre, consists of a Buddhist sutra artfully obscured with splattered paint and colourful concrete patches.

While in Edmonton, Wong took a painting class at MacEwan University, but he considers himself self-taught. “For a long time I knew I was good. I was on this artist’s path. But one thing I wanted [was] to become a better person before becoming a good artist.” He worked as an art and design teacher and as a creative director at Telus before becoming a full-time artist in his mid-30s, moving to Vancouver in the late 1990s. Although his work isn’t overtly concerned with politics, his own background has had an impact on his career. “As a diasporic Asian artist,” he says, “it’s not easy to get your foot in the door in the art world.”

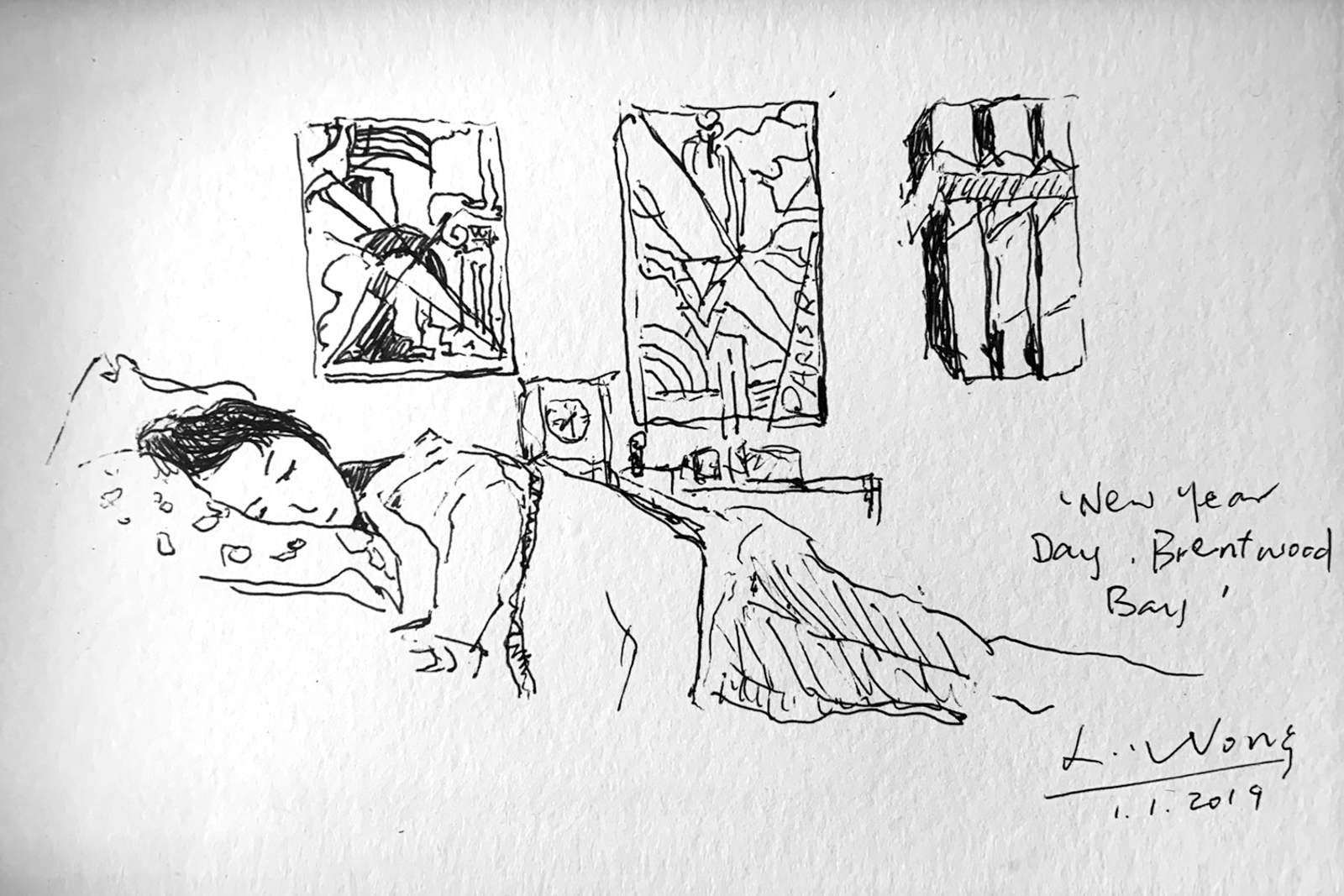

New Year’s Day (Brentwood Bay), 2019. Lam Wong. Ink on paper, 5 x 7.5 in.

Slowly but surely Wong has gained attention from prominent local artists, including his recently departed mentor, Michael Morris, and photographer Jeff Wall. This past January, Wong curated Views In and Out of Vancouver, Wall’s first Vancouver solo exhibition in 14 years. “We have this kind of mutual understanding because we both studied art history,” he says about working with perhaps Canada’s most famous living artist. “And we’re both kind of self-taught.”

The rest of Wong’s year is busy with a fall show at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, a series of publications, and various curatorial projects. When I ask whether his own work has made him a better person, he speaks only in general terms: “Art can make one a better person if one is conscious and present.” At those words, my own mind turns to the image of a reclining house cat, of a husband seeing Vermeer in the form of his wife across the table.

Read more local Arts stories.