As the Canucks gain momentum in the NHL’s new all-Canadian division (thanks in part to the irrepressible Brock Boeser, a hot Swedish rookie named Hoglander, and a long-awaited hat trick from Brandon Sutter), we look back at these striking images from the team’s earlier days. Contributor Tom Hawthorn takes us behind the scenes of these rare archival photos, exhibited last year at the Polygon Gallery in North Vancouver.

With its a blur of wooden sticks, frozen vulcanized rubber, and metal blades on ice, hockey can be a challenge to capture for photographers trying to freeze an instant of the action in increments of 1/1,000th of a second.

This never stopped Ralph Bower and his colleagues at the Vancouver Sun and Province, whose remarkable images—now on display at the Polygon Gallery’s exhibition The Canucks: A Photo History of Vancouver’s Team—reveal the action, the pathos, and the humour of life on the ice and in the stands.

These rare snapshots, which chronicle the Canucks both as a minor-league team in the old Western Hockey League (pre-1970) and as a franchise in the major-league National Hockey League, sought beauty in the ordinary and revelation in the extraordinary—all on deadline.

Here’s a look back at the moments they captured and the players they immortalized.

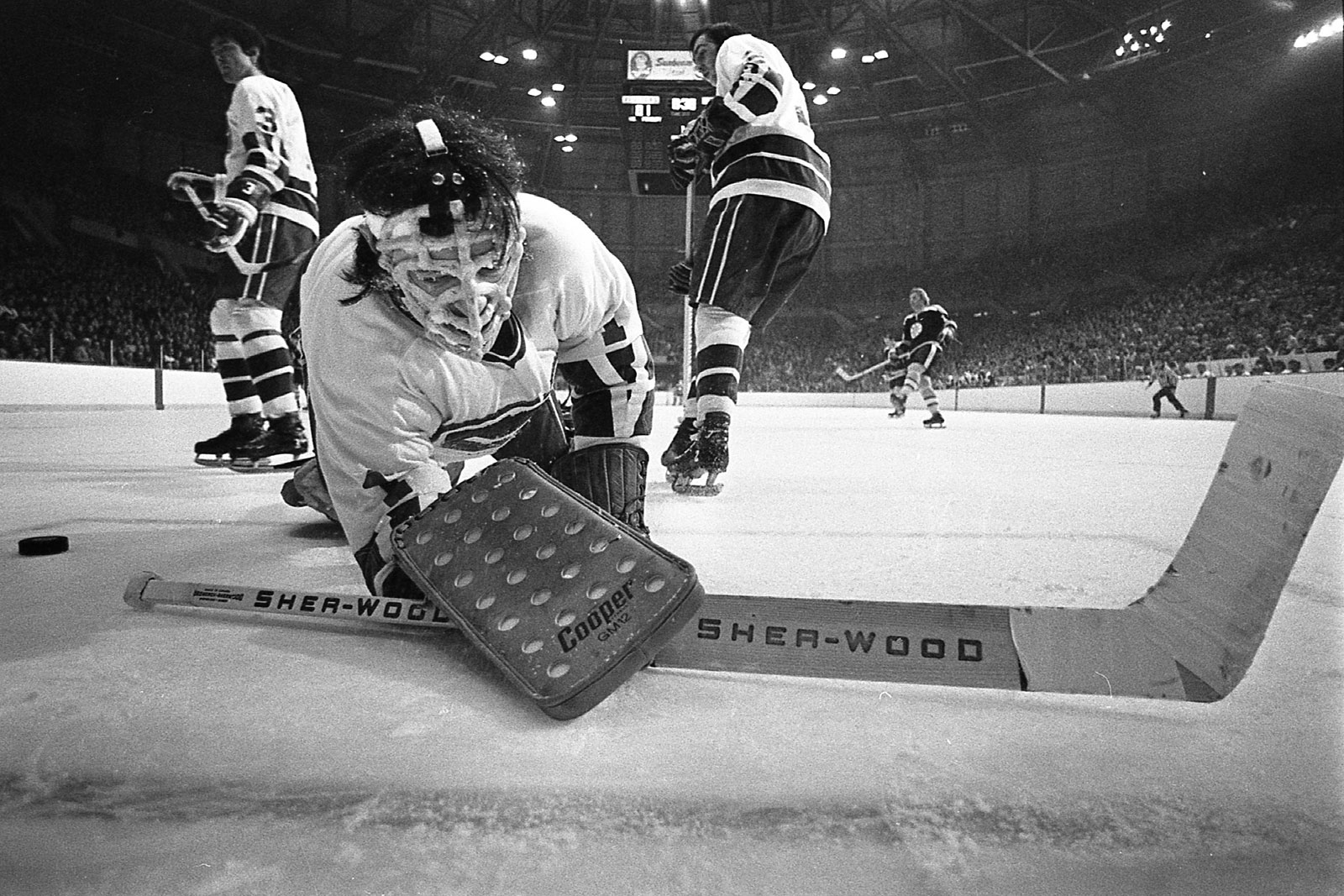

Goalie Dunc Wilson gets a cage-full of ice

Ralph Bower joined the Vancouver Sun as a copy boy in 1955 before becoming a photographer. He sought a unique angle on the game in the Canucks’ second season in the NHL. After negotiating with the league, the team, and the goalies, Bower rigged a Nikon camera with a wide-angle, 20 mm lens in a metal birdcage inside the goal.

To snap the shutter, Bower had a cord implanted in the ice leading to a spot in the stands behind the Canucks net. He could snap an image by pressing a contraption like a doorbell. A first attempt was thwarted when the Zamboni ice-cleaning machine severed the cord in the ice. He would have to try again.

On December 11, 1971, the Canucks had a 5 p.m. puck drop for a game against the mighty Boston Bruins to be aired on Hockey Night in Canada. “I had the same view as the goal judge,” Bower says. “I was so close it was like I was sitting in his lap.”

Bower had only one period to get his shot. The goalies would be trading ends for the second period, and he had made no arrangement with the Bruins. The clock was ticking down in the final minute when two crisp passes sprung Boston centre Fred Stanfield behind the Canucks defencemen.

Stanfield moved the puck to his backhand as goaltender Dunc Wilson sprawled in a valiant effort to block the shot. Stanfield sent up a spray of ice as he cut across the goal, shovelling a backhander into the net. The red goal light flashed, the whistle blew, and the clock stopped with 38 seconds left in the first period.

A wide-eyed Bower, “shooting blind,” in his words, snapped the shutter remotely from behind the net. Only later in the darkroom did he realize what he had captured. “A lot of little things worked out,” he says.

Photo by Ralph Bower/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

In the photo , the puck has bounced out of the goal. (You can see it resting in the crease at left). Framed by beaten defencemen Pat Quinn (No. 3, at left) and Jocelyn Guevremont (No. 2), Wilson is slowly rising to his knees from the ice. His mask is covered with a spray of slushy ice from Stanfield’s skates.

Wilson is beaten this night by Stanfield, Ed Westfall, the great Bobby Orr, Phil Esposito (twice), and Garnet “Ace” Bailey, who, almost 30 years later, will be killed aboard the first jetliner to crash into the World Trade Center.

Wilson does not finish the game. After Boston’s sixth goal, a frustrated coach pulls him in favour of George Gardner. The Canucks lose, 6-2. The one memorable souvenir of an all-too-typical midseason game for the fledgling Canucks is Bower’s image of Wilson looking like a defeated soldier on the front lines of the frozen Eastern Front.

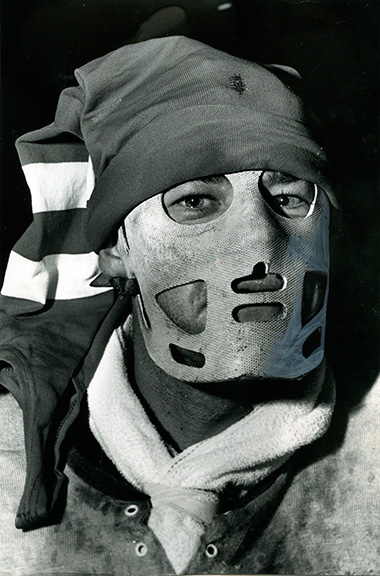

Goalie George Gardner was always a character

Goaltenders are eccentric. George Gardner stood out even in a fraternity known for oddballs.

Born into a blue-collar family in the working-class Montreal suburb of Lachine, Gardner kicked around the low minors and in and out of the NHL. Like Charlie Hodge and Orland Kurtenbach, Gardner was a goalie who wore the sweaters of the old and new Canucks.

Photo by Bill Cunningham/Province/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery

He liked to gamble on football and the horses. His devil-may-care attitude sometimes extended to hockey games

When he was once pulled after letting in too many easy goals, he warned an elderly woman sitting behind him to beware. “Ma’am, if you see a puck, coming you’d better duck,” he said. “Don’t depend on me to stop it.”

During a practice on November 1, 1968, he wrapped a sweater around his neck and donned a hockey sock as a toque. That night, the Canucks defeated the Phoenix Roadrunners, 4-3.

The Canucks’ first goal ever in the NHL

The first NHL game in Vancouver was played on October 9, 1970. A national audience watched on Hockey Night in Canada, while 15,062 paying customers crowded the Pacific Coliseum.

The premier was on hand and the mayor delivered the ceremonial opening face-off. A 73-man pipe band made some noise. Cyclone Taylor, still spry at 87, stepped onto the ice to cheers; he had led Vancouver to a Stanley Cup championship 55 years earlier with the Millionaires of the old Pacific Coast Hockey Association

The singer Juliette (Sysak) Cavazzi, who performed under her first name and was given the rhyming nickname Our Pet Juliette, sang the national anthem while wearing a silver evening gown, her arms outstretched as if beseeching the heavens for glory.

With the Canucks trailing 2-0 early in the third period, the defenceman Barry Wilkins took a pass at the Los Angeles blueline, spun to avoid sprawling Kings defenceman Gilles Marotte, then slipped a low backhand toward the net as he fell to the ice.

Photo by Ralph Bower/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery

The Canucks (in white sweaters) celebrated their first goal in NHL franchise history.

Len Lunde (No. 24, far left) joins pint-sized Andre Boudrias (helmet) and Dale Tallon (No. 19) in hugging Wilkins. On one knee, Denis DeJordy (No. 30) fishes the puck out of the Los Angeles goal.

Wilkins, who was readily identifiable on ice with his Beatles haircut and mutton chop sideburns, was playing in only his ninth NHL game.

The World’s Strongest Man hoists six Canucks

Doug Hepburn was a scrawny child born with crossed eyes and a club foot. He was bullied as a schoolboy. He began weightlifting, learning the sport from articles found in glossy magazines at the corner drugstore. When he won the 1953 world heavyweight weightlifting championship in Sweden, he became known as the World’s Strongest Man.

The mayor hired him as a bodyguard to ensure he did not lose his amateur status and would be in Vancouver to compete at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games. Hepburn won the gold medal.

Photo by Roy LeBlanc/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery

Eight weeks later, Hepburn performed a stunt between periods of an exhibition hockey game at Kerrisdale Arena on October 3, 1954. Six players with the Canucks of the Western Hockey League stood atop a specially constructed platform, linking arms and holding on to hips. Hepburn, wearing his weightlifting singlet, crouched beneath before using his back to lift more than 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms). The stunt raised $100 for the B.C. Athletic Round Table Society.

At the same event, Hepburn announced he was turning professional. He would perform feats of strength at exhibitions across the country before going on to have a brief career as a professional wrestler.

The players on the platform are Billy Dea (wearing Jack Lancien’s No. 5 sweater) and Fred Brown (No. 9) with Chuck McCullough, Ron Hemmerling, Gord Kerr, and Doug Adam.

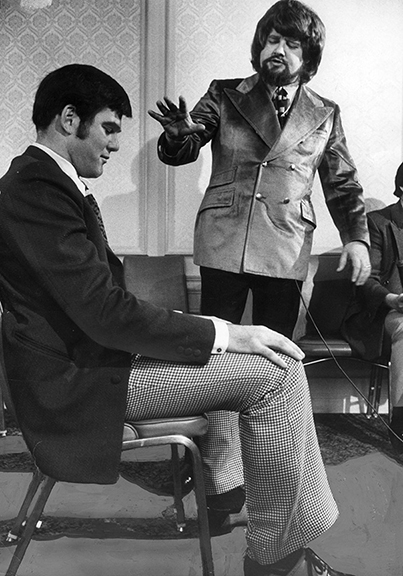

The Canucks’ first superstar gets hypnotized

Rosaire Paiement was called Cracklin’ Rosie after the Neil Diamond song. From the farming town of Earlton in Ontario’s isolated Timiskaming region, Paiement only had four NHL goals to his credit before emerging as the Canucks’ first superstar. He led the club in its inaugural season with 34 goals.

Great things were expected of him the following season, but he scored only one goal in October. None in November. Zero in December. Zilch in January.

He was in the midst of a 33-game scoring drought when the Australian-born hypnotist and prestidigitator Reveen the Impossiblist, a Canucks fan, offered to break the jinx by putting the struggling skater under his spell.

“Why not? Nothing else is working,” Paiement said ruefully.

Reveen, wearing a wide-lapelled leather jacket, performed his hocus-pocus at a luncheon at the Hotel Georgia on February 1, 1972. The performer promised Rosie would score in his next game, which was in Oakland against the California Golden Seals.

Photo by Dan Scott/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

He did not. The drought was at 34 games.

Then, 35.

He did not score in his 36th straight game. Nor 37th or 38th.

“Some voodoo’s on my head,” Rosie lamented.

The sad-sack Canucks went to Boston to play the Big Bad Bruins. They were whipped, 9-1.

The one? Scored by none other than Joseph Rosaire Wilfrid Paiement. With an assist to Reveen.

Captain Orland Kurtenbach charms fans in 1970

A farm boy from Cudworth, Saskatchewan, Orland Kurtenbach was a hockey player from central casting. The square jaw. The rugged good looks. All those consonants in his name as hard as his bodychecks.

He was a journeyman player often used to kill penalties when the fledgling Canucks drafted him with their second pick (fourth overall) in the expansion draft.

Photo by Deni Eagland/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

The centre was 33. The Canucks made him their captain.

On a midweek evening before their debut game in 1970, fans were invited to meet the players for autographs and photographs at the Pacific Coliseum. Boys gathered around Kurtenbach. One tried on his right hockey glove. It went past his elbow.

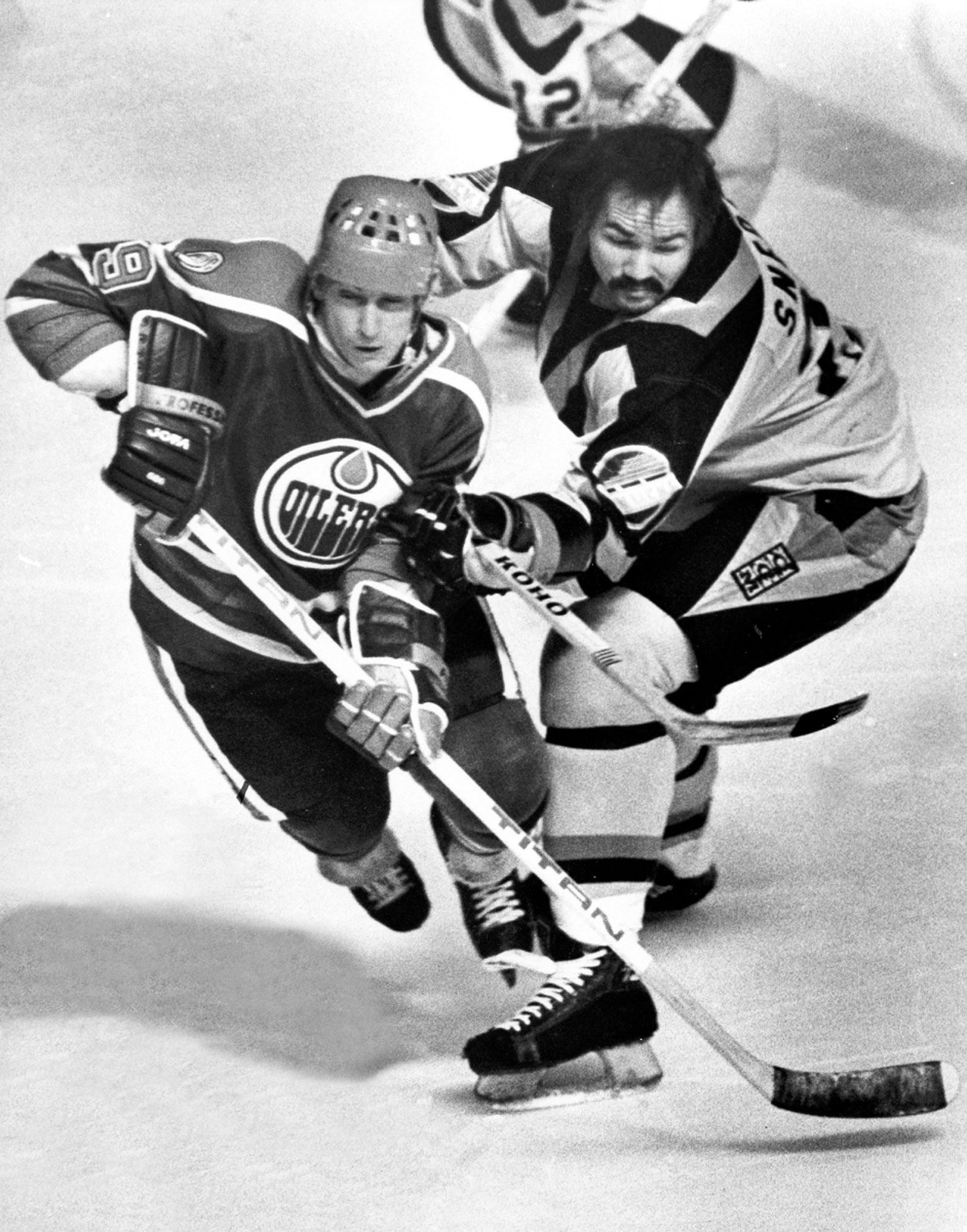

Defenceman Harold Snepsts checks a famous Oiler in 1982

Fans loved Harold Snepsts. We chanted his first name in two-tone, singsong fashion. We cheered him for decking opposing players.

A big, physical, stay-at-home defenceman, “Hair!-olllld, Hair!-olllld” kept scorers away from the Vancouver net. He was a solid, lunch-bucket guy with a big moustache.

Photo by Ralph Bower/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

Sure, he coughed the puck up in overtime of Game 1 of the 1982 Stanley Cup finals. What working joe hasn’t had a bad day on the job?

The other mug in the photo? Snepsts is laying on the lumber to some guy named Gretzky.

Fans cheer for the Stanley Cup finals in 1982

The unheralded, overachieving Canucks, who relied on the stellar goaltending of “King Richard” Brodeur, managed to claw their way into the Stanley Cup finals in 1982.

Despite losing the first two games to the Islanders in New York, the Canucks returned home to be greeted by jubilant fans on May 12.

Photo by Dan Scott/Vancouver Sun/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

Two more losses and a riot were still to come. They say you never forget your first time. They are right.

Pavel Bure celebrates a goal in the last game of a tough season

The Russian Rocket was our favourite Russian export since vodka. Pavel Bure celebrates his 51st goal in the final game of the 1997-’98 season on April 19.

The season began with a win on the road (against Anaheim in Tokyo) but was downhill after that. The coach was fired, then the general manager. Popular players Trevor Linden, Martin Gelinas, and Kirk McLean were sent packing.

It was one of the worst campaigns since Napoleon marched on Moscow.

Photo by Colin Price/Province/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

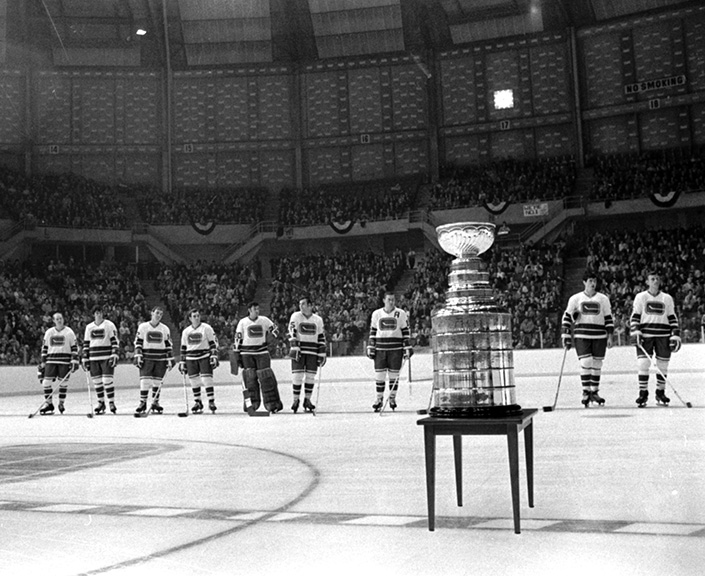

The Stanley Cup makes a rare visit for the Canucks’ NHL debut

For the first home game, the NHL brought the Stanley Cup onto the ice at the Pacific Coliseum. The silver mug had been won by the Vancouver Millionaires back in 1915. (The players’ names are engraved inside the fluted sides of the bowl.)

It was hoped the Canucks would bring Lord Stanley’s glorious trophy back to the coast. Fifty years later, we’re still waiting.

Photo by Brian Kent/PNG Files/Courtesy of Polygon Gallery.

This story from our archives was originally published on March 9, 2020. Discover more Community stories.