At the stroke of midnight, as Friday turned into Saturday on Aug. 11, 2001, Vancouver rock band The Beans began a concert at The Sugar Refinery on Granville Street. Forty-eight hours later, they were still playing. Rightfully regarded as one of the Canadian underground music’s greatest achievements, the concert has become a Vancouver urban legend.

Here is how it went down, as remembered by the people who were there.

Prehistory

The Beans weren’t in it for fame. Their particular brand of dreamy post-rock wasn’t made for the airwaves of the late ’90s and early ’00s. Instead, they built a fanbase playing regularly across Vancouver—in particular, at the much-missed Sugar Refinery.

Stefan Udell (then: guitarist, The Beans; now: PhD student in musicology at the University of Toronto): Back in 1995 or so, before we were a band, Andy [Herfst: drums, loops, and sound effects], Tygh [Runyan: guitar], and I went to see The Dirty Three. That was a formative experience for us. I think we imitated them in some ways. We weren’t professional or motivated to make a career out of music—we were just friends having fun together. This attitude determined the nature of our music. Even when we recorded, our songs were largely improvised.

Tygh Runyan (then: guitarist, The Beans; now: musician and actor based in Los Angeles): We played almost any chance we could get. We’d play the Commodore and house parties. We were essentially the house band at The Sugar Refinery—in its early days, anyways, when Granville Street was strictly sex shops and single rooms. The Refinery was Steven Horwood’s vision and gift to all of us: long gone now, but a place that is tattooed forever on my soul that I revisit frequently in my mind. It was a gathering place and watering hole for outsiders: the creative and the deranged. Sometimes it got violent. Steven and The Sugar Refinery were godsends for the band.

Ida [Nilsen] walked in one night when we were playing there, pulled out her trumpet and just joined in. What a gift! We asked her to join our band that night.

Richard Folgar (then: photographer and Beans friend and fan; now: archivist): We all loved The Sugar Refinery. It had this appeal and pull that was unique and different from everywhere else in the city. Sure, there were other music venues, but they were just that: venues. There was nowhere else to congregate unless you wanted to hang out at douchebag bars. The Sugar Refinery was this hidden gem in the city that spoke to so many marginalized individuals: musician, artist, punk, indie, queer, broke, you name it. We all felt safe and accepted there. It was for many people this place of refuge and a creative and artistic sanctuary.

Doretta Lau (then: DJ and writer for The Georgia Straight; now: author and managing editor at Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong): The Sugar Refinery was a place for people to come together. When Frog Eyes played, it was over capacity and we were turned away at the door. Because we went regularly, we snuck in through the back entrance and bought merch to make up for the fact we hadn’t paid cover.

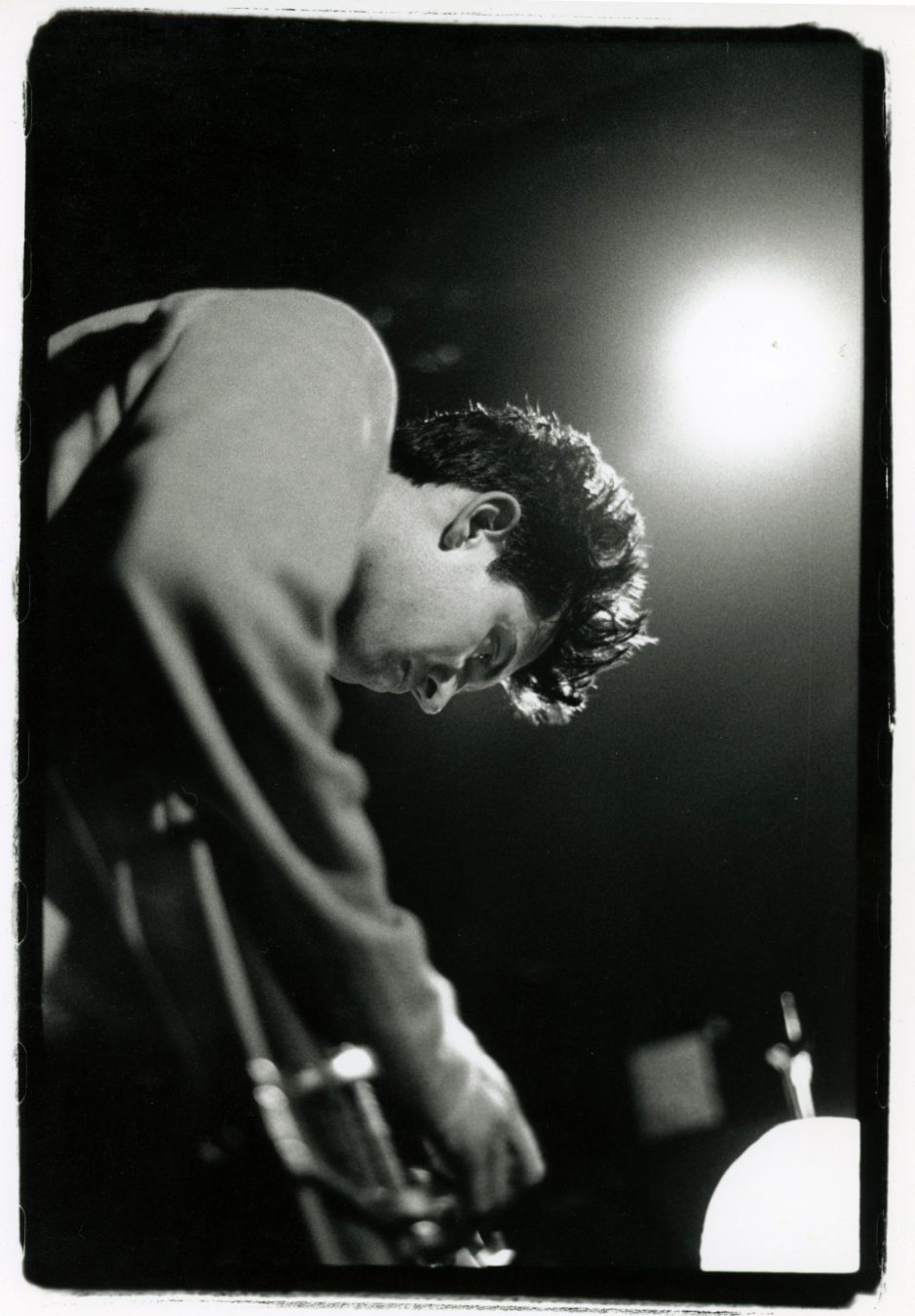

Photo by Ann Goncalves.

Origins

The idea of playing a 48-hour show didn’t come out of the blue. For a band that enjoyed the simple pleasures of playing and exploring ideas together, it seemed like a (somewhat) logical creative step.

Runyan: We would often jam for hours on end and get lost in the music. In the beginning, before The Beans, we’d have parties at friends’ houses where we’d invite people who could play and all jam in the key of E for hours. People who didn’t play an instrument could pick up a pot and play percussion. You’d take a break when you felt like it, and join back in at any point, but the music would remain continuous. It was soul-stirring music, at least for me.

We would play all night at The Sugar Refinery for six or seven hours, maybe with one short break, on a regular basis. We were young and had punk spirit. We were entranced by the space and immersed in the music, eager to let her take us wherever she wanted to go. Also, it was convenient to just keep playing when fights would break out near the pool table.

Udell: Andy and I came up with the idea on the bus, coming down the hill from SFU. We were taking a Javanese Gamelan course and both studying contemporary classical composers that often wrote long pieces. It was born from that atmosphere. We came up with the final form and all the details as a band.

Runyan: We’d been discussing a show that Low played with some other bands in tribute to La Monte Young, that I think was 12 hours long. We wanted to do something similar. Andy asked, ‘How long do you think we could play?’ Twenty-four hours seemed like something we could do without even trying. Forty-eight posed a threat.

Photo by Ann Goncalves.

The Plan

Acknowledging that a concert of this length couldn’t work as an unstructured improvisation, The Beans honed their jam strategies.

Udell: We came up with a framework to improvise within. We had built the framework on a 24-note Gamelan melody that was a motif throughout the song. And each note was the musical key of each hour of one day, which we repeated on the second day. Each hour also had a theme that we improvised on in the given key. All of this was dictated to us through an hourly projection designed by artist David Crompton. We had a loose schedule when people could take a break; never more than two people at a time. It didn’t end up like that, it was much more loose.

Runyan: I was obsessed with the concept. For the poster, I tracked down a printer that agreed to do a run of non-digitized, old-school, chemical-process, white-on-blue blueprints which would fade over time, eventually disappearing completely. This notion of impermanence seemed perfect. This epic piece of music performed only once, born of ether and destined to disintegrate. I remember seeing rain starting to fall that weekend and was happy to think about the posters we’d put up around the city beginning to bleed and dissolve while we played.

The Build-Up

Back then, gigs were promoted through posters, local press, and word of mouth. Once the news of this show began circulating around the city, people started making plans to ensure they could witness at least portions of the marathon set.

Lau: When I heard The Beans were putting on a 48-hour show, I was excited and curious as to how they would pull off a feat like that. I called a few friends to see when they wanted to go.

Folgar: At that point, they were playing so much that it didn’t seem like a big deal. It wasn’t until about two days before it was to begin that I started thinking about logistical things. ‘Are they going to sleep? Are they going to be wearing the same clothes the whole time? When are they going to eat?’ I didn’t feel that it was something that I needed to witness, but something I wanted to see to support my friends.

Photo by Ann Goncalves.

The Weekend

Forty-eight hours proved to be an intense experience, both for the band and the curious who’d gathered to listen.

Udell: It was a very intense and taxing thing to do: more of an endurance trial than I’d imagined. At one point I abandoned the band and left the venue for a long time. After 16 hours of straight playing, it was my turn to take a break and I was dehydrated so I went home and slept. I regret that to this day, leaving my bandmates like that. They never said a single thing to me about it. They were great.

Folgar: I lived about a three-minute walk away from The Sugar Refinery, so I was there all the time. The 48-hour show was no different. I wasn’t working that weekend, so I was there for approximately 36 hours of it. If I wasn’t there, I was home sleeping.

Runyan: One of the amazing things about the experience was the way in which word spread while we were playing the show. At first it was a lot of regulars and people who knew us and enjoyed our shows. But word was getting out, and more and more people started showing up to see this insane thing. They would arrive to see people in sleeping bags and the band playing. The Sugar Refinery itself was straight out of some idyllic punk rock bohemian dream. I remember noticing the first few newcomers entering and wandering around, enveloped by the event. The “WTF” looks on their faces were beautiful to see. As the music took hold and the delirium increased, I became less aware of how many people were there. Saturday night turned into one of our old all-night party jams. We tuned the antenna to the Velvets station, rocked hard, and most people stayed until dawn. Andy was a driving force on the drums, and once The Beans locomotive hit top speed, we would hang on until the track ran out.

Even for us, who were young and conditioned to playing long sets, that second night was really tiring. We’d already been playing for 24 hours and we’d lost Stefan for a bit. Sunday morning looked rough. We stayed the course and played meditative ambient music. Damon [Henry, bass] and I performed a kind of “cut-up” experiment, where we read two novels simultaneously at varying rhythms and varying durations to create a new text entirely. Some of us caught some rest, and we all took turns eating. After we regained some strength, we were back to playing full force, and launched into a feedback-drenched Spacemen 3 cover among other hours that have escaped memory.

The Grand Finale

Word had spread across the city over the weekend. As Monday loomed, The Sugar Refinery was full to capacity.

Lau: I was happy to see a lot of friends drift in and out and then come together for the last stretch. The final few hours had this energy to it, a kind of crescendo to a victorious moment.

Udell: What sticks in my mind the most is the final hour. We were all in a sort of trance and ended up singing together. The place was so full there was only a little circle of space around us, yet you could hear a pin drop. When the clock hit midnight and the 48 hours were up, the response from the people there was amazing.

Runyan: At the very end when our voices joined together in harmony, I started to hear more voices. I immediately became aware that the place was completely full of people. Standing room only. I had no idea! I looked around at all those shining faces. I’ll never forget it. We all chanted the final meditative minutes together as one.

Photo by Ann Goncalves.

Looking Back

The Beans and The Sugar Refinery are both distant Vancouver cultural history now, but their legacies of creativity live on in those lucky enough to have experienced them.

Lau: I came to realize I love durational performances—in music, theatre, art, or sports. That 48-hour concert showed me that it was possible to set a difficult goal for one’s artistic practice and to make it happen. I feel lucky to have been a part of that audience, to experience that energy and feel like part of a community.

Udell: Through the course of the concert, I’d developed an acute sense of time fluidly speeding up and slowing down. It felt like we were manipulating our experience of the speed of time with the music in a concrete way. That experience changed the way I listen to and play music.

Folgar: As proud as I am that my friends managed to pull off such an ambitious and physically challenging endeavour with what appeared to be such ease, it saddens me that their achievements haven’t been fully recognized. The 48-hour show seems to have become a myth: “Did it really happen?”

Runyan: It’s all faded into memory. But it never ended. And truthfully, it never began.

These interviews, conducted separately, have been edited and condensed. This oral history story from our archives were originally published on February 21, 2018. Read more about the Arts.