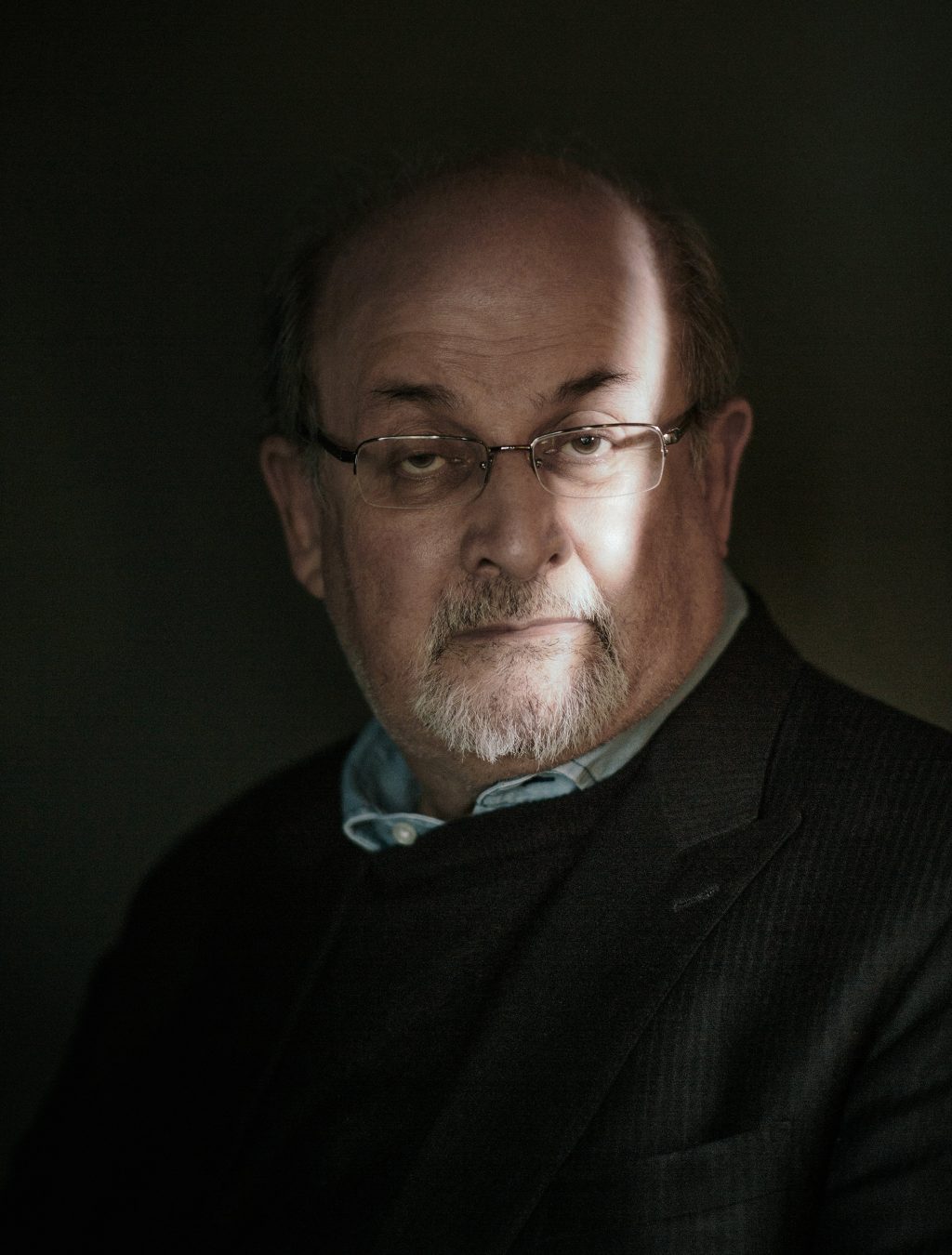

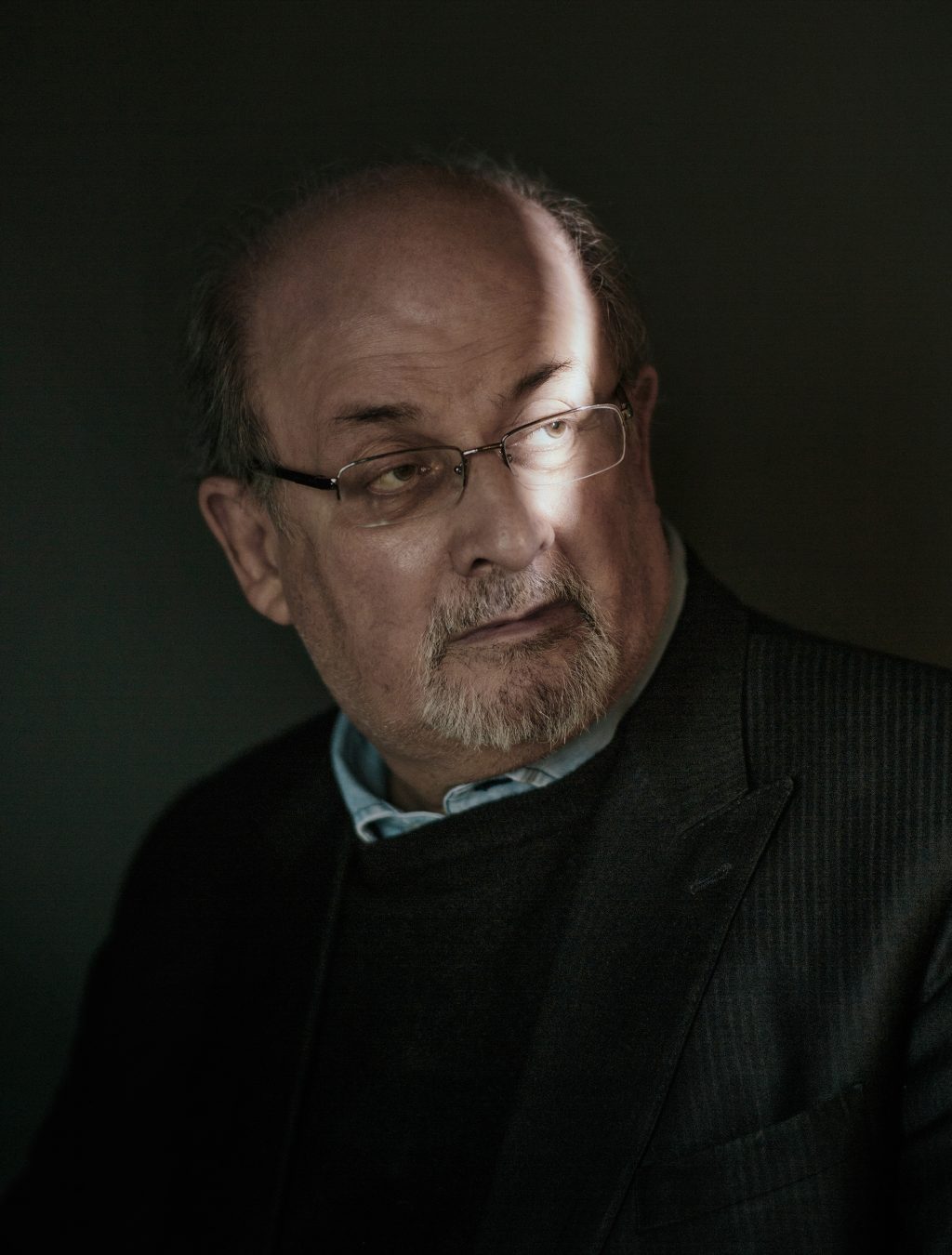

Author Salman Rushdie has been famous in literary circles for decades, for his writing, certainly, as well as for the fatwa that was very publicly declared against him after his book The Satanic Verses incurred the wrath of Iran’s religious leader in the late 1980s. In the years since, he has received a long list of awards, published more novels, stories, and works of non-fiction. Now 73, he has an active Twitter account, where he recently announced he’s working on a new book set in India. We sat down with him when he was in Vancouver for the Writers Festival in 2017, for this feature from our Spring 2018 issue.

Salman Rushdie is about to board a Harbour Air flight from Vancouver to Victoria and is remembering all the times he has seen parts of Canada from above. As a 24-year-old copywriter for an ad agency working with Air Canada, Rushdie was flown around the country, arriving first in Vancouver then taking in Montreal, Quebec City, Toronto.

His most recent image of Canada was also from a high-up vantage point. A friend sent him an imaginary map, drawn up after the election of the current U.S. president; New York and California were blended into an expanded Canada.

That’s a country Rushdie says he would like to live in.

Location matters to him. He cannot write his books without knowing first where the setting is for his characters. For nearly two decades, he has lived in New York, after spending most of his adult life in England, the last few years of which were spent in hiding. All three cities he has lived in have been attacked by terrorists over the last 20 years: London, New York, and Mumbai, which he precisely, deliberately, calls Bombay.

In the first chapters of Rushdie’s latest book, The Golden House (Penguin Random House), patriarch Nero Golden forbids his family from mentioning Mumbai, the place they are fleeing. “Tell them we are snakes who shed our skin. Tell them we just moved downtown from Carnegie Hill. Tell them we were born yesterday,” Nero orders his sons as they leave the airport for their new home in New York. “Say we are from nowhere or anywhere or somewhere, we are make-believe people, frauds, reinventions, shapeshifters, which is to say, American.”

The facade set up by Nero is dismantled quickly for the reader. What was supposed to be the grand reveal of the novel—a tragedy involving the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack that drove the well-heeled Golden family out of their country to seek an even more decadent life in America—is uncovered early on, signifying to the reader that there is a much darker mystery still to unfold.

Rushdie says he knew he wanted to write something about the Mumbai attack that killed 166 people right after the incident took place, but wasn’t sure exactly how. The character of Nero was also taking shape in Rushdie’s mind years before he knew he wanted to put them together in the same novel.

It was in his youth that Rushdie first heard about Domus Aurea, an opulent golden house built by the fiddling Emperor Nero after a fire destroyed most of ancient Rome. So lavish was the home that Nero’s successors, embarrassed and angered at the scale of it, stripped and buried the palace. Within 40 years of Nero’s death, Dominus Aurea had been obliterated, built upon, and hidden from view.

“The question with a mystery is: what do you tell the reader when?”

Although Rushdie didn’t know how The Golden House would end, he knew there were a few separate ideas that would eventually come together to make sense. “That’s normal for me,” he says. “I suddenly see how they’re all pieces of the same jigsaw and how they all fit together. It’s happened so often, I almost expect it to happen. The last missing piece was the location.”

He found that location in a spot he knew well: a Greenwich Village townhouse once briefly occupied by Bob Dylan, where his friends, the artist couple Alba and Francesco Clemente, currently live. Rear yards of individual homes on a block below Bleeker Street open to form a communal space known as the MacDougall-Sullivan Gardens.

The apartment and gardens became a stage. Rushdie could imagine looking out the back window and across the yard, gazing into someone else’s window. Peering into private lives is how narrator Rene first encounters the Golden family, then deliberately inserts himself into their world. “It was a private world surrounded by a public world. What I’m doing is telling a story inside a story,” Rushdie says. “Here is this story about this family inside the tragedy. All around it is the larger catastrophe of America.”

In the book, Rushdie explores the criminal history of the Golden family and the deceptions they create to cover their past. It’s the closest to a mystery novel as anything he has written. “The question with a mystery is: what do you tell the reader when? When I was first working on it, I didn’t reveal anything about their past until very late in the novel, then I thought, ‘That’s going to annoy people to have this empty space where the truth is,’” Rushdie says. “The fact is, they have to keep a secret. There’s no reason I need to.”

Rushdie has been famous in literary circles since his second novel, Midnight’s Children, was published in 1981. Seven years later, he became the most well-known writer in the world when The Satanic Verses was published and incurred the wrath of Iran’s religious leader, who ordered a fatwa on him. He had to live in hiding and with protection, but others associated with the book did not have the same security. The Japanese translator of the book, Hitoshi Igarashi, was fatally stabbed; a translator in Italy was attacked; and in a targeted fire set by zealots aimed at Turkish translator Aziz Nesin, dozens of people were killed in a hotel, though Nesin survived.

Today, Rushdie travels on subways, goes to see baseball games, attends concerts. The death threat against him is not perceived as a danger any longer, and indeed, has even become a pop culture joke: the 2017 season of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm, which includes a cameo by Rushdie, centres around a musical that Larry David’s on-screen persona wrote about the fatwa.

When Rushdie arrives at the Cactus Club Coal Harbour, just a handful of people recognize him. There are no visible security guards accompanying him, although at a reading for the Vancouver Writers Festival at the Chan Centre the night before, the RCMP were there along with security staff. At the event, after Rushdie spoke, a man approached the author with a box. It was empty, but the word “Dye” was on it—an incident that organizers at the Vancouver Writers Festival say was a poor, insensitive, and worrying joke. But at no time, says Rushdie, was he concerned for his safety. “It’s been over for 20 years. It’s not a factor,” he says. “It went on for nine years, I’ve lived in New York now for 19 years and there’s no security issue there, nor is there here.”

The last seven of those years have been a particularly productive period for him, with The Golden House being his fourth novel since 2010. It started with his second children’s book Luka and the Fire of Life, followed by his memoir, Joseph Anton, two years later in 2012. Then, two novels: Two Years Eight Months and 28 Nights published in 2015, and The Golden House published in September 2017.

His novel before The Golden House was all about genies, spirits, and other mythical creatures, along with allegories and illusions. This new book is decidedly different. “The notion of truth and what is truth is so under attack now,” Rushdie says. “It made me think one of the reasons why The Golden House doesn’t contain any fantastic elements is that I thought this may not be the time for this kind of writing.” Reality is his unshakeable focus now. He believes his readers want the truth, and they can handle the truth.

This cover story from our archives was originally published in our Spring 2018 issue. Read more in Arts.