Sonja Ahlers has been in bed for two days. She’s recuperating from the emotional excavation of her life’s work. It’s been a few days since the opening of Classification Crisis, Ahler’s retrospective at the Richmond Art Gallery, and now, back home in Victoria, the artist is sitting in the calm after the storm.

“Having my work on display, that’s always vulnerable, and to see 30 years of work that’s been very carefully curated,” she tells me from her home, before trailing off in thought. “It was emotional because it also just brought up a lot of old wounds. You know, going through the archive of all the old work.”

Five years in the making, Classification Crisis brings together decades of Ahlers’ work—politically charged zines, confessional poetry, and feminism-fuelled collages that have so far been overlooked by the wider art community. Now, the RAG’s walls are adorned with looseleaf pages taken from her zines and pink-paletted collages of magazine cut-outs and vintage photographs, along with the containers for her extensive archive of letters and scraps.

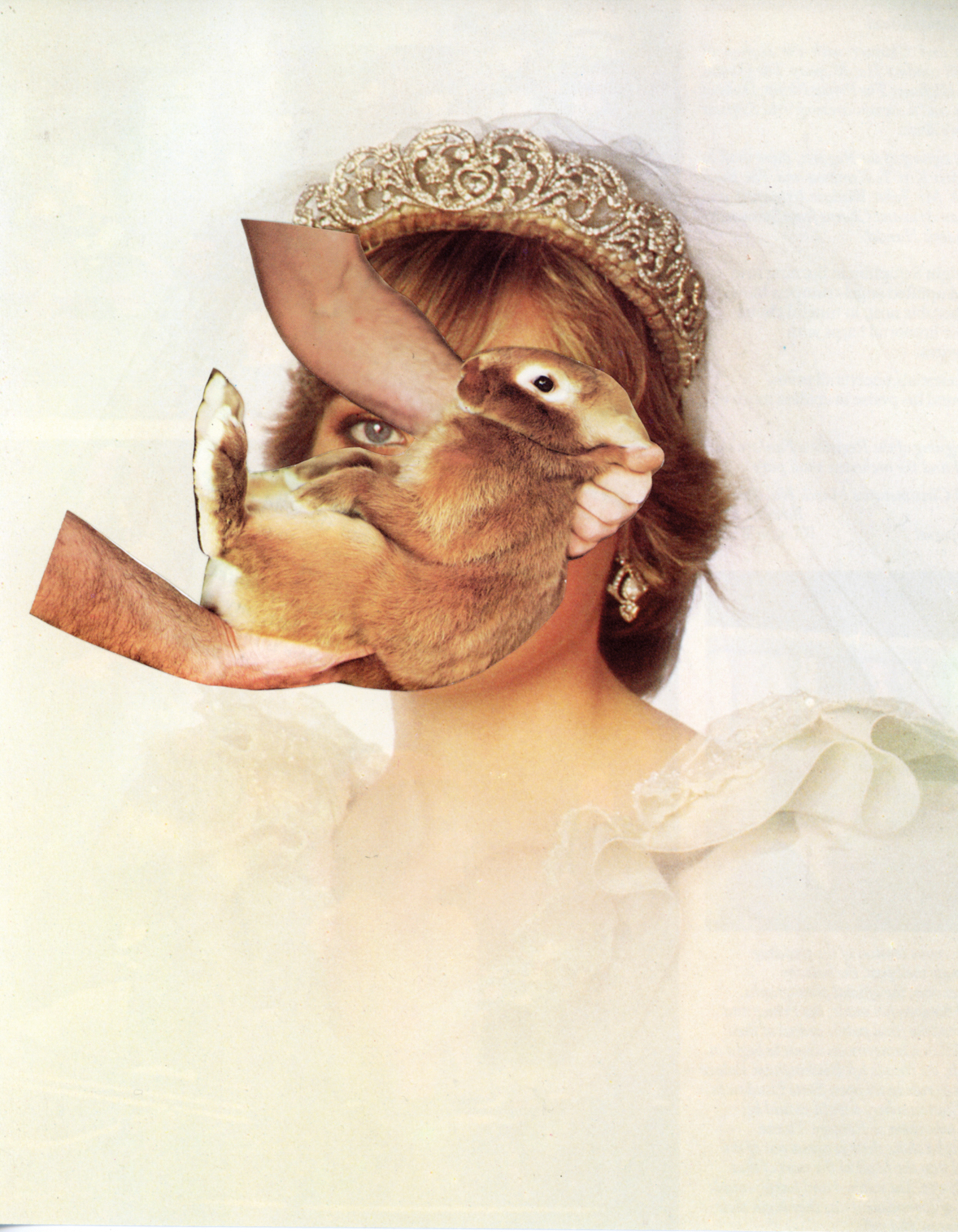

Sonja Ahlers, Diana, 2022, collage, 8 1/2” x 11”. Courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition not only catalogues Ahlers’ contribution to Vancouver’s sometimes exclusive art community, but it also pays homage to the cultural context of her work: the emergence of DIY culture in the late ’90s and early 2000s, when punk rock, third-wave feminism, and the birth of the internet converged into a mismatched, plaid, and stapled-together art scene.

Victoria-born Ahlers came into artistry at an iconic time in the Pacific Northwest. Further south, the Riot Grrrl movement was taking shape in Washington, where women in the punk rock scene gathered to discuss sexism within the community. All-girl punk bands wrote songs about rape, patriarchy, and anarchy. And their shows, often in underground venues, created spaces for young female crowds to express rage—the grrr in Riot Grrrl.

Meanwhile, zines—handmade, illustrated, and then photocopied “magazines”—recorded an alternative cultural conversation. Riot Grrrl-era zines were political, and the writers and artists engaged communities with their political and feminist ideas. The self-published booklets also established a visual vernacular: graphic typesets and scratchy illustrations, collage-like compositions of text and images overlaid in chaotic disorder.

Sonja Ahlers, Hawks, mixed media, 2020, 12” x 16”. Courtesy of the artist.

Ahlers’ zine-making, however, was first influenced by autobiographical graphic novels and comic books, particularly those from Drawn & Quarterly, a Montreal-based publisher she discovered during a stint in Quebec in her early 20s. “I was doing a lot of scrapbooking and diary writing and letter writing,” she recalls. “I started doing mail art, writing and confessing in letters to friends. That’s when I realized I could start photocopying and making small books. I started forging relationships with anyone who I felt a kinship with—a musician or a writer. I would actually source their mailing address and then I would just send them a small book. And that’s how I started creating this network pre-internet.”

That’s also how she first connected with Kathleen Hanna, lead singer of punk bands Bikini Kill and Le Tigre and widely considered one of the forebears of the Riot Grrrl movement. “I started sending little books to Kathleen Hanna. She, to me, was the mothership,” says Ahlers. “She’s very political. And her activism was incredibly inspiring. She was in the trenches, as far as I was concerned. So I wanted to support her somehow and give her something back.”

Hanna loved the zines, which were messy and personal—a poetic vomiting of confessional angst. “The early zines are just this outpouring of emotions and thoughts and ideas,” says Ahlers. The two stayed in touch, inspiring each other from across the border, and are still friends today. (Hanna wrote an essay about Ahlers in a book that accompanies the exhibition, of the same name.)

Sonja Ahlers, Rabbit Queen, 2020, mixed media, 16” x 16 1/2”. Courtesy of the artist.

But despite this link to the heart of the Riot Grrrl movement, Ahlers considers herself a fringe part of the scene. “I really struggled with scenes, even though I’ve been a part of them, allegedly. I still always feel outside of things no matter what,” she says. “I kept my head down, to do my own work and to find my own way and my own voice.”

Ahlers’ journey to find her voice has taken her across Canada, from Victoria to Vancouver to Whitehorse, each city informing her work and filling the gap the previous city left. Whether it was an unfinished college course, a government job, or a relationship, Ahlers was always leaving something behind to find something else.

In Victoria, she hit a wall creatively. In Vancouver, she found herself an outlier in an art scene that was more concerned with fine art than DIY zines. Still, she matured into installations and collage work, managing to exhibit at a few galleries. After seven years and a breakup, she picked up and moved her life again—this time to Whitehorse, where she worked as a page in the Yukon Archives. It was a stark difference to city life, slower and quieter and much colder. But the archive job attracted fellow artists. She spent hours sifting through old records and Gold Rush pamphlets, photocopying documents featuring typography that inspired her.

Ahlers’ art took a backseat, however, when her mother fell ill in 2014. She returned to Victoria to care for her, and once she passed, Ahlers was left with an extensive archive of her mother’s belongings—along with the archive of her own art. It took years to sift through it all.

“I find the process of sorting your past—it feels like you start to piece together your life again. And take control of it too,” says Ahlers. The process of classifying disparate pieces wasn’t too different from her approach to art. “My art, you can see it’s very fragmented and scattered. So the archive was representative of me and my work. I was able to finally clean it up, and I felt like a custodian.”

Sonja Ahlers, Ferret, 2017, watercolour, collage, 9” x 12”. Courtesy of the artist.

That custodial work lent itself to Classification Crisis, which was meticulously curated by Godfre Leung and incorporates Ahlers’ archive of materials into the exhibition. A wall of bankers boxes labelled with Post-it notes is a recreation of Ahlers’ own organizing system of letters, tapes, photographs, and diaries. Throughout the room, binders with clear plastic sleeves are filled with hundreds of images, illustrations, and words from various magazines, books, and newspaper clippings—just some of the source material for her zines and collages. It ranges from vintage illustrations of cats to hastily scribbled lines of poetry (“I’m just not because I can’t”) to excerpts from textbooks about the origins of art on ancient cave walls.

The exhibition feels random and nonsensical at first. But digested together, it sparks subjective emotions, which is the point. To me, the poems about witches, magazine clippings about eating disorders, and collages of Princess Diana—a figure Ahlers related to as an outlier—evoke a tragic sense of girlhood specific to the culture of the early aughts.

Ahlers is a collector of these evocations, a custodian of images and words—of which her work contains a thousand possible combinations.

Classification Crisis continues at the Richmond Art Gallery until November 5. Read more stories about the arts.