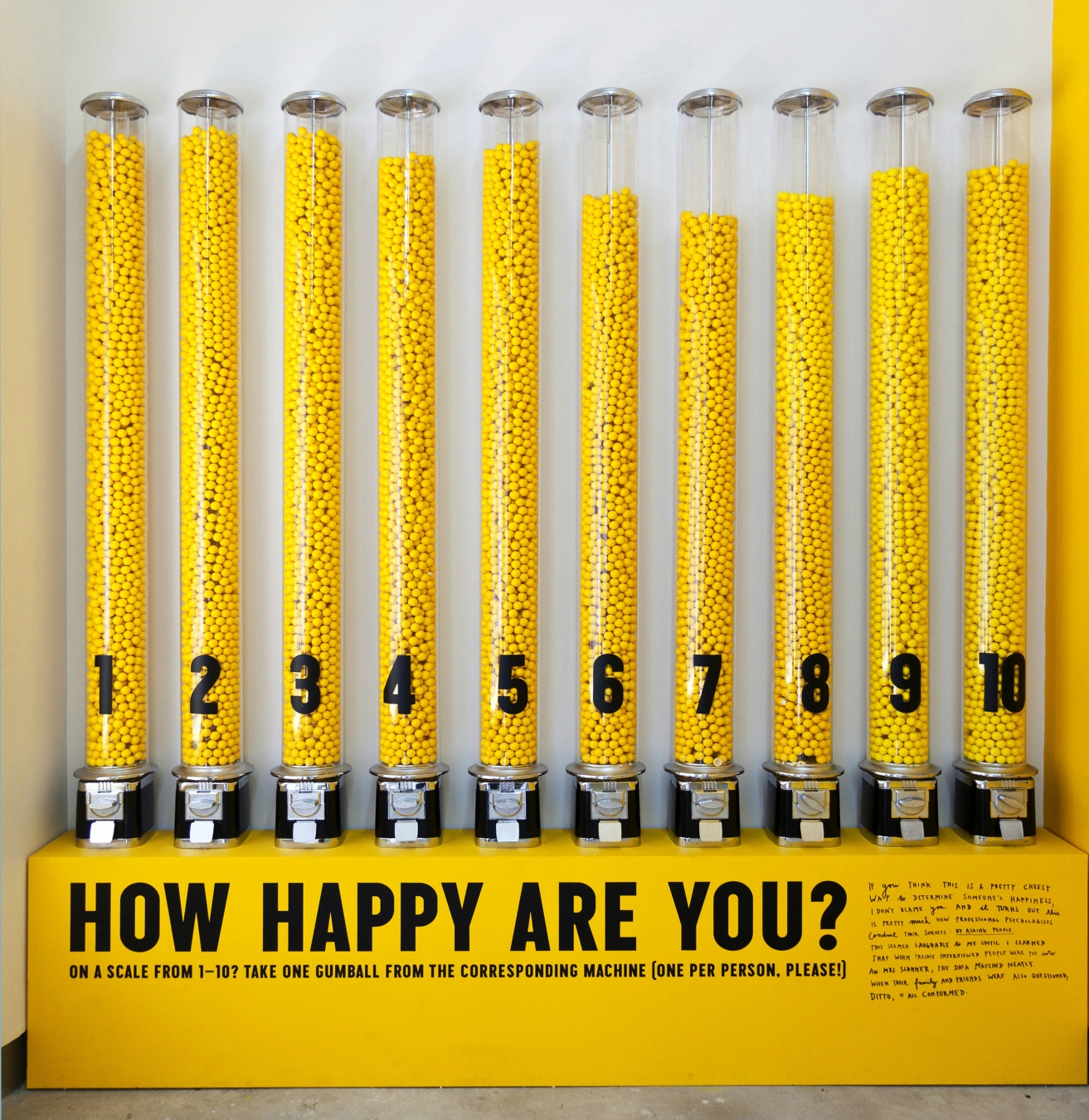

“How happy are you?” A row of giant gumball machines accompanies the probing question at the entrance of Stefan Sagmeister’s “The Happy Show”, on at the Museum of Vancouver now through September 7. The exhibition is an exploration of what happiness means and how it can be attained, the content amassed by the award-winning graphic designer over a span of 10 years. Known for his album artwork and work in advertising, Sagmeister’s “Happy Show” premiered at Philadelphia’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 2012. With a recent survey from Statistics Canada revealing Vancouver to be the country’s least satisfied city, the exhibition could not have come at a better time.

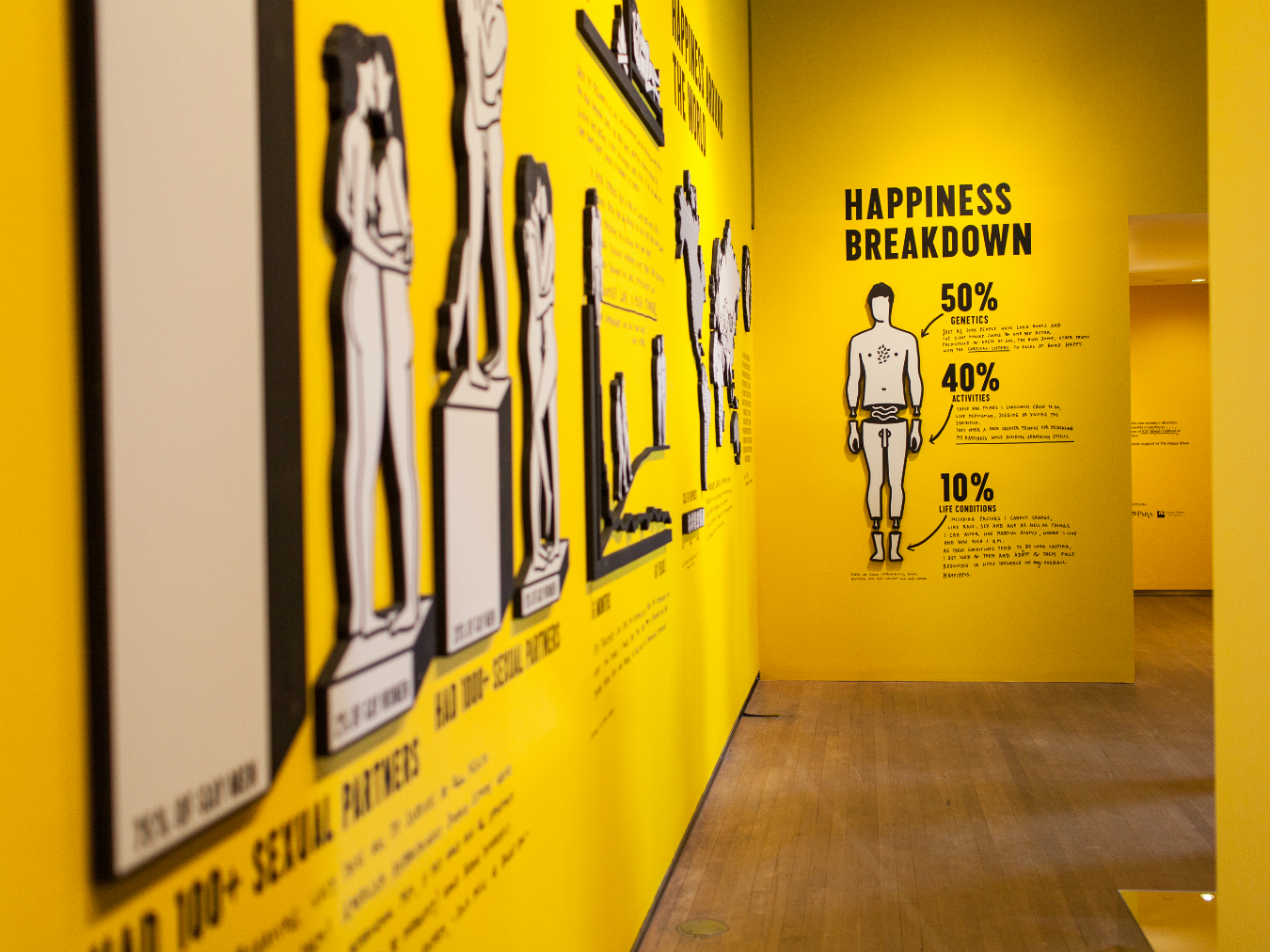

Sagmeister’s show stands as both an art piece and a collection of research—one man’s view on happiness propelled by concrete statistics from the likes of Jonathan Haidt, professor of Ethical Leadership at NYU’s Stern School of Business, whose book The Happiness Hypothesis served as inspiration for Sagmeister’s research. The first room of the exhibit beams sunshiny yellow from its walls, one of which is lined with the gumball machines, others displaying statistics by way of graphs, diagrams, and maps. The visuals depict the relevance of sex, child-bearing, and the amount of time one’s life is spent learning, working, and in retirement. Sagmeister playfully admits that he cherry-picked the research that related to him the most and ignored everything else. It is this tailoring that renders even the factual portion of the exhibit so personal.

“I was anxious that I’m not really the right person to make [this] exhibition,” Sagmeister says. “I’m not really in the right profession—you really would need to have some sort of Psychology background to make this properly. While, on my own personal happiness, I am, of course, the world’s number one expert.”

The other rooms are driven by Sagmeister’s personal maxims that he has found helpful with his journey through depression: “Be more flexible”, “If I do not ask I will not receive”, and “Now is better” are some of the mantras that fill the space. In the centre of one room a spotlight shines down on a stationary bicycle, facing a wall mounted with unlit tubes of light. Pedalling the bicycle powers up the neon lights to reveal more of Sagmeister’s maxims—one of which unexpectedly advises to seek discomfort; not perfection.

The bike is one of many opportunities for interaction within the exhibit. From a station where visitors write down an animal they believe is doing well (the results are projected onto the wall), to a display of sugar cubes spelling out “Step up to it” that lights up with bright colours in response to the viewer smiling at the display, a sense of connection is established between visitor and art piece. This social link is emphasized by a giant inflatable monkey bearing a sign that reads “They are right”, a reminder that we do what we believe in, and an encouragement to see the world through another’s eyes. This variety of art and activity keeps the visitor engaged, always pushing them to return to that initial question: how happy are you? It makes one wonder if we actually know what it means to be happy.

Even with one of Sagmeister’s wall inscriptions reading, “I am usually rather bored with definitions. Happiness, however, is just so big a subject that it might be worthwhile to try and pin it down”, the exhibition never tries to offer a solid definition of the word. Rather, Sagmeister shares what he, as an individual, has learned about his own happiness. One key comfort is his realization that certain characteristics of his, such as becoming accustomed to things and taking them for granted, are not so unique. This particular quality is in fact something a massive population of humanity goes through, as Sagmeister discovered through his research. “I find that comforting,” he says, “that I’m actually more embedded in what it means to be human than I would have thought.”

Upon leaving the exhibit and removing a gumball from the machine, visitors, armed with Sagmeister’s proverbs, are perhaps now better equipped to answer the daunting question. A glance at the gumball levels helps each of us find our place in a collective level. And suddenly, we’re not so alone.