According to Lewis Bennett, the director behind the documentary The Sandwich Nazi, audiences who screen his film will fall into one of two camps: strong support, or vehement opposition. There aren’t, it seems, any shades of grey here. “I think it’s a love it or hate it kind of film,” the Vancouver-based Bennett explains. “I think most people will go in and they’ll have a great time…or they will have a not-so-great time.” The name alone invokes a certain understanding (yes, it is a reference to the notorious Seinfeld “Soup Nazi”), and the film has certainly caused a stir.

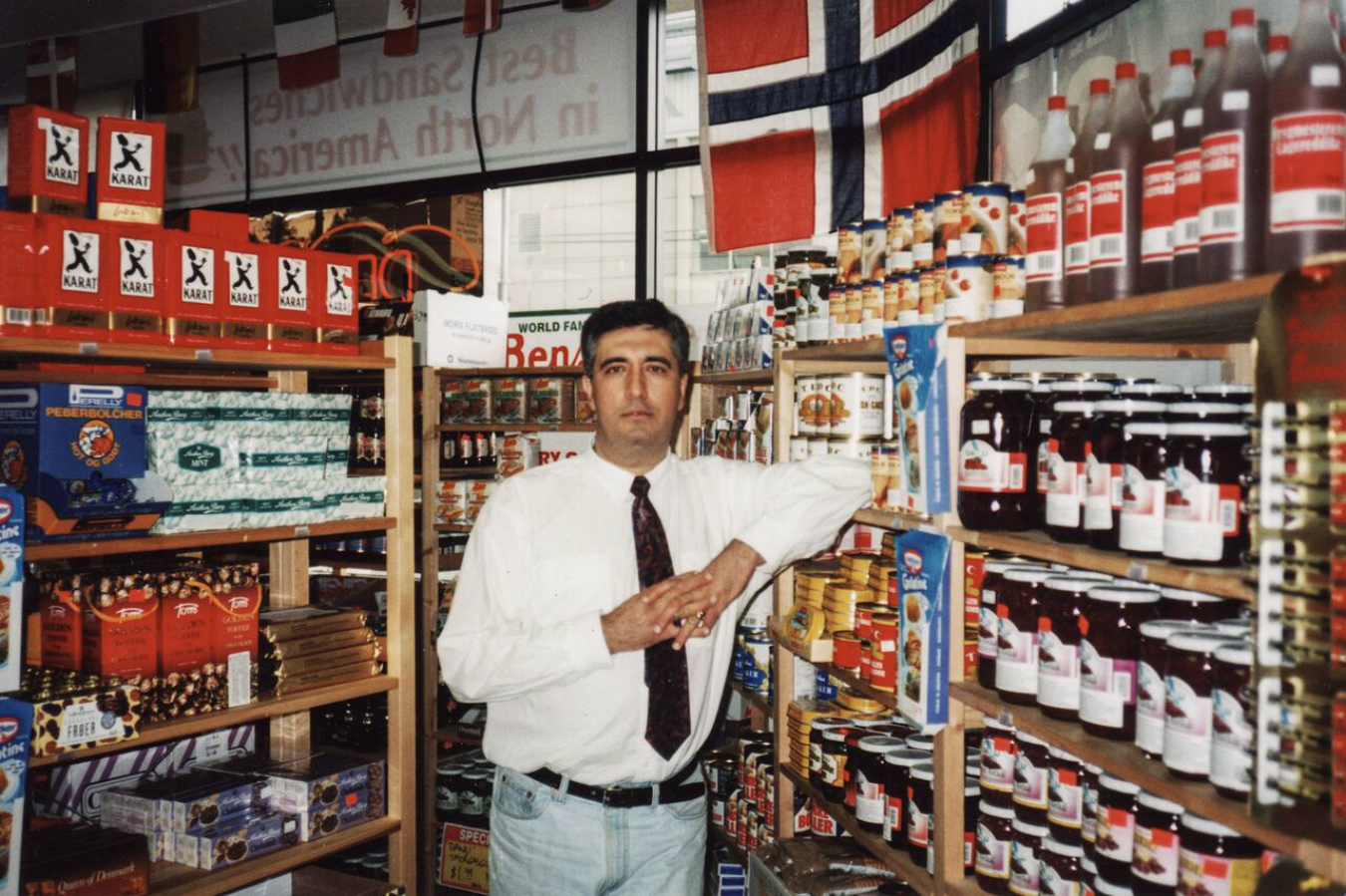

Following Lower Mainland deli owner Salam Kahil—a man known as much for his raunchy stories (from his former life as a male escort) as for his humongous sandwiches—The Sandwich Nazi holds nothing back. It is entertaining at times, as Kahil, a Lebanese immigrant, tells jokes and slices meat, insisting customers say please and turn off their cellphones. The story is filled out with clips from his loyal customers, old and young, who come to his deli for his company almost more than his food. The film is also largely uncomfortable, though, demonstrating Kahil’s utter lack of filter. No tale is too vulgar, and it can be hard to watch, no matter how open-minded the viewer.

For all the ways that Kahil bares it all (literally) for the camera, it doesn’t feel that his true personality is captured in the film. Aside from a scene where he reflects on his trip back to Lebanon to see his family, in which he tears up while reading a letter he wrote to his brother, what we see of Kahil is a caricature, an outer layer. It’s an observation not lost on Bennett. “I don’t know how many times in the film [Kahil] really opens up,” Bennett reflects. He too would have liked to see more of what’s below the “surface, show level”, he says, and it is a refreshingly candid admission.

The Sandwich Nazi was originally shown as a short film, but then over the last few years was reworked into a feature—Bennett’s first. It premiered at South by Southwest in Austin and is currently part of the Vancouver International Film Festival, with a final showing on Oct. 3. It has been an interesting experience for the young Bennett, who has recently found himself, and his movie, criticized by Kahil. It seems the deli owner never understood that the filmmakers would be seeking wider distribution for the movie, and is taking issue with its commercialization—something Bennett says he tried to explain, but acknowledges he could have been more explicit about. To Bennett’s disappointment, it has essentially ended their once amicable relationship. “It’s not like it’s a film where we’re exposing someone who’s doing something bad, like a Michael Moore-type movie where you’re out to get somebody because they’re bad,” says Bennett. “I feel sympathetic towards [Kahil] and I like him as a person, and I feel like the film celebrates him.”

It does indeed champion Kahil, who is shown in the film making hundreds of sandwiches and handing them out for free in the Downtown Eastside, something he does often. “You can tell he really cares about those people, and there’s no distance between him and them,” Bennett says, explaining that Kahil talks to the homeless community the same way he does everyone else: with a foul mouth and a crude punchline. This is where he shines the most.

Kahil is an undeniably interesting character, a multifaceted human with boundless energy and enigmatic thoughts (he once, for example, read this writer’s palm and determined she would live forever). As for Bennett, he is happy the film is out there in the world and being watched by audiences, be they lovers or haters. He calls the sour ending with Kahil “unfortunate”, exhaustedly adding, “But what can you do?” Perhaps the only thing he can do is keep making movies. He agrees, barely skips a beat before adding, with a smile in this voice, that maybe he’ll switch to fiction.