In a cramped, subterranean room, a black-and-white film glows from a computer monitor. Members of Spain’s upper class in formal attire sit around a banquet table. There’s clattering dishware, butlers bustling, and murmurs of small-talk emanating from the periphery. Then a bulging, warbling synth sound wafts into my ears, filling a lull in the onscreen conversation.

“Going for kind of a borborygmus sound,” Matthew Tomkinson tells me, standing at a keyboard off to the left side of the screen. He’s one half of the experimental audio duo known as Magazinist, alongside collaborator Andy Zuliani, who is plucking away at an upright bass next to Tomkinson. I’ve come to visit their Gastown studio to watch them rehearse for an upcoming show and discuss their artistic process.

Originally meeting as students at Simon Fraser University, the duo began creating together shortly after realizing that they both had backgrounds in music, in addition to their shared study of theatre.

Tomkinson called Hotel Fata Morgana—Magazinist’s 2019 debut installation—“pretty ambitious, for a first outing.” They cut together found footage of Fata Morgana mirages and projected it in a local venue, composing and performing live synth music to accompany it.

Related stories

- Vancouver-Based Modern Biology Creates Music From Sound Waves Emitted by Plants

- In an Unfocused World, “Listening Bars” Demand Our Complete Attention

- Vancouver Opera Reframes the Cultural Narrative in Madama Butterfly

After that, the pair bounced between different kinds of projects. They’ve composed for film, accompanied theatre and dance productions, and held residencies at the Lobe Spatial Sound Studio and Simon Fraser University. They even put together a composition based on water data from the City of Richmond, for the Richmond Maritime Festival. “We did a lot of weird online work during the pandemic,” Zuliani tells me.

However, if there’s one thing Magazinist has become particularly known for in the last few years—at least locally—it’s the sort of show that I’ve come to watch them practise: live-performed original rescoring of classic films. Previously, they’ve performed accompaniments for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, F.W. Murnau’s Faust, and Theodor Dreyer’s Vampyr. They’re gearing up for Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel during my visit.

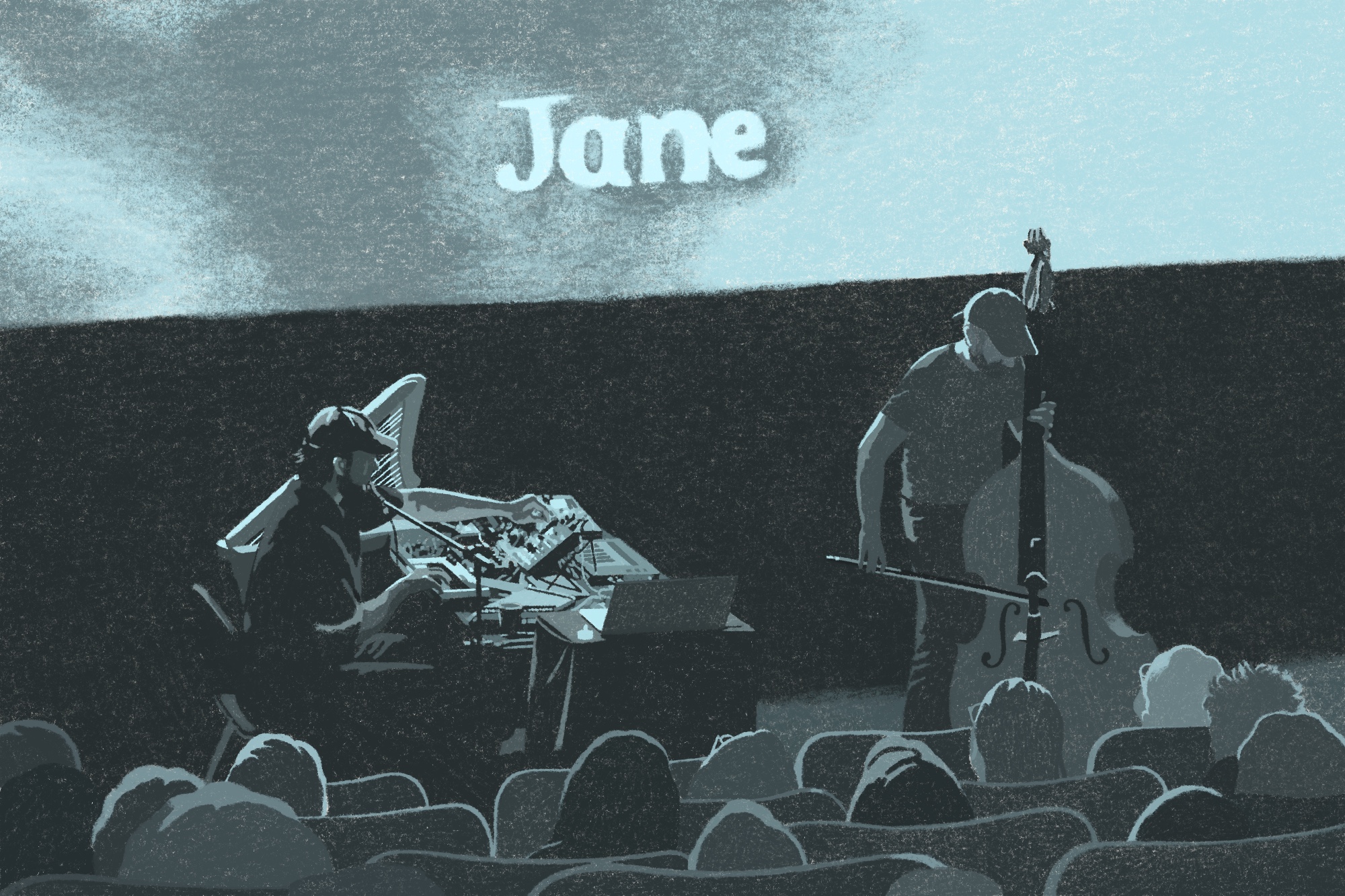

Typically, Tomkinson and Zuliani stand just below the projection, surrounded by an array of instruments that run the gamut from the mundane to the outlandish.

For the Buñuel rehearsal, the pair has assembled a table full of different instruments: a lap guitar, to be used with a magnetic resonator; an arrangement of cymbals, both conventional and makeshift; and a platter full of wine glasses filled to different levels with water, along with an assortment of shotgun and lapel-style wired mics, with suitably echoey filters applied liberally.

The film itself is a critique of Franco’s Spain, following a group of bourgeois Spanish socialites attending a dinner party, who upon realizing they cannot leave the dining room, descend into delirium and depravity over the course of three days. According to Zuliani, the plan is to mirror it with their performance, as if props fell out of the screen and onto the table.

A scene from The Exterminating Angel.

“I’m going to pop champagne. We have an underwater microphone that’s going to go into a vase, and I’ll basically decant champagne into it, and we’ll just have that as a sound source. Kind of fizzy, bubbly, gurgly sounds that will, over the course of the film, get quieter and lower,” he tells me. “Off the top it will be quite noisy.”

To Tomkinson and Zuliani, the film informs the score’s instrumentation.

“It’s kind of [about] finding ways of not steamrolling the film. Not turning it into a Magazinist show that happens to have a film playing in the background. It’s part of us, and we’re part of it,” Zuliani says.

When they performed their Metropolis score, the film’s tone dictated an industrial, electronic composition—well within their synth-oriented wheelhouse at the time. Each film has prompted branching out since then, which suits the multi-instrumentalist tendencies of both members.

Zuliani describes that score of Faust as being rooted in a kind of alchemy, so making things sound like something other than themselves was a guiding principle.

“At one point I was reciting Satanic verses into a microphone with my voice down, like, two octaves. We had lots of things going through really weird effect chains to transform the sound. We had a violin that was going through a bunch of hardware gear to make it sound like everything but. We also had a hand-built instrument.”

A scene from Faust.

In addition to inspiration, the films impose different limits with each project.

“This film, more than any we’ve done, with the dialogue being there, a lot of what we’re doing is, both inadvertently and intentionally, kind of like sine-tone oriented,” Tomkinson says. “The tones are very clean, in a way.”

The Exterminating Angel has a more conventional audio complement than some of Magazinist’s previous performances. There’s no musical score, but there’s dialogue and diegetic sound, including brief moments of music when characters sing or play piano, and that presents a new consideration for their live-scoring.

“Finding ways of scoring around the frequency range of speech is a really interesting challenge. To not accidentally wander into the same band as people who are speaking,” Zuliani says.

How Magazinist has approached the actual playing of the score has also changed as they’ve moved from project to project.

“Our last three film processes involved extensive spreadsheeting. We had key centres for each scene. We’d have time markers,” Tomkinson says. “This one is the first time we’re going fully vibes-based. No paper to reference.”

The two are able to do that in large part because they’ve become more comfortable and capable of playing around each other in the moment.

“I feel like we’re pretty quick to figure out our roles for the scoring, in a way that has gotten better every single time. We know not only what each of our cluster of instruments is, but also procedurally, how we can compose through playing together,” Zuliani says.

“Who’s contributing the fundamental rhythm or the bass or the heart of it, and who’s doing the ornamentation, that has gotten, for me at least, easier and easier as we’ve gone. It feels at this point intuitive—we just kind of know what to reach for, for certain kinds of tones or scenes.”

These kinds of live-scoring performances are exercises in fitting together sounds thematically and aesthetically, which is where the wine glasses and champagne pouring come in. For those kinds of additions, the need to exercise the appropriate level of restraint is a constant.

With the opportunity to incorporate so much novelty into each performance, it’s important to know the right time to deploy a new element.

“We don’t want to use them for the whole film and have their charm wear out,” Tomkinson tells me. To Zuliani, the urge to reach for the next thing is something they’re always wrestling with.

“With things like the wine glass and physical objects, it’s like ‘what’s the longest we can wait,’ so that when they come in it feels impactful and we’re not stalling out on novelty,” he says.

“Doing Faust, we had an orchestra pit where I think we each had, maybe six—I think I had 10 different things to play. It felt like the choreography of choosing when to switch was very important, because you don’t want to use everything too early.”

Playing with where the audience’s attention should fall is something the duo is mindful of—whether the audience should forget there’s a performance and just experience the score as part of the film or focus on the live playing at the expense of the visual element.

This was evident throughout Magazinist’s actual performance of The Exterminating Angel, which screened for packed audience at the VIFF Centre in July. The subtler, more ambient tonal aspects complemented the ever-heightening surreality of the film, while other elements pulled attention to the pair standing beneath the screen. Tomkinson’s shimmering playing of wine glasses, Zuliani popping a bottle of champagne and pouring it into a mic’d-up vase. Watching it in the theatre, it’s easy to forget—and then be sharply reminded of—the live aspect of the show. That push and pull is by design.

“The best moments have been where it feels like we’re a lens that’s helping to focus certain aspects of the film to the audience,” Zuliani says.

Read more arts stories.