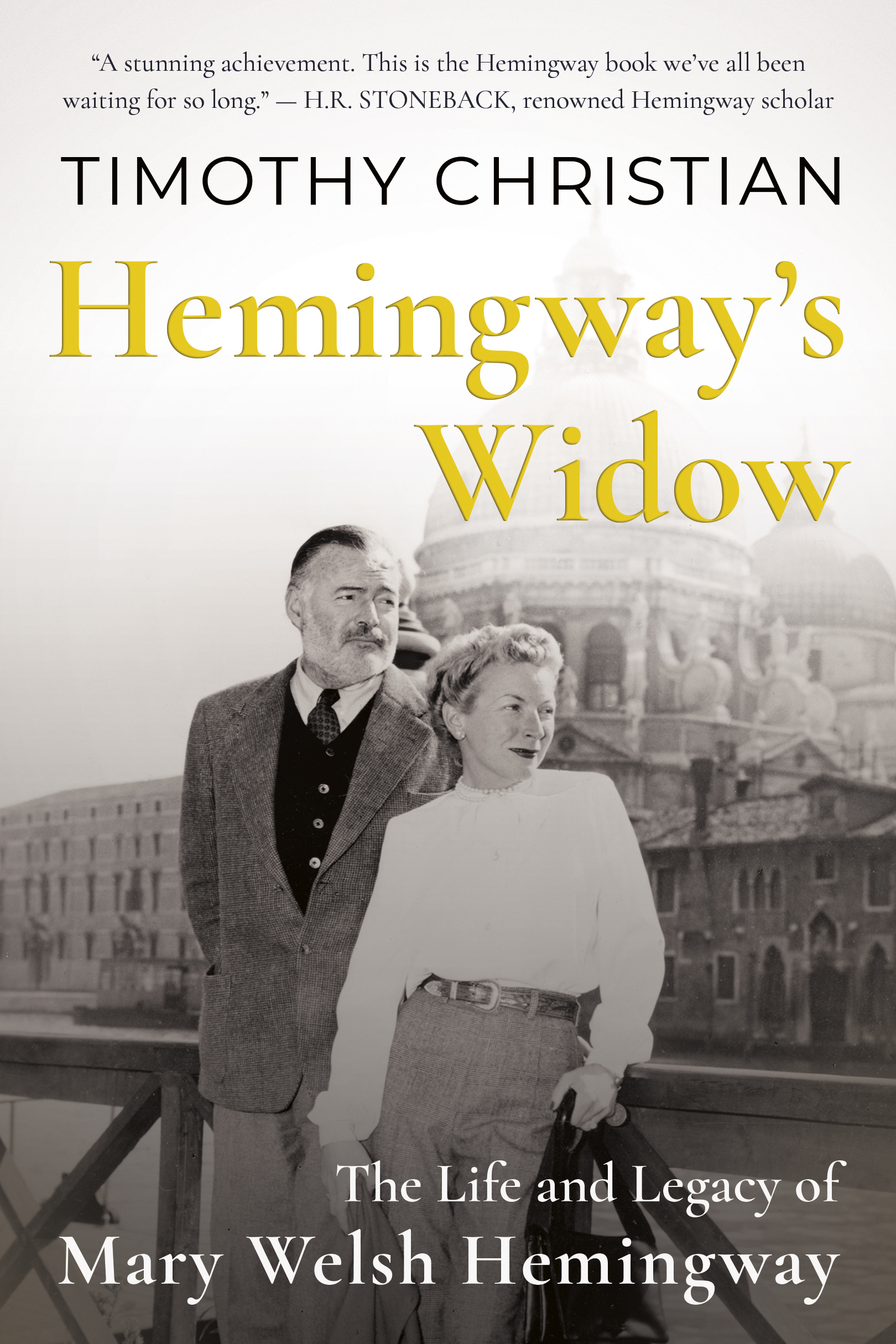

In a new book, Vancouver Island author Timothy Christian explores the life of Mary Welsh Hemingway—and through her, a fresh perspective on one of the most celebrated writers of the 20th century.

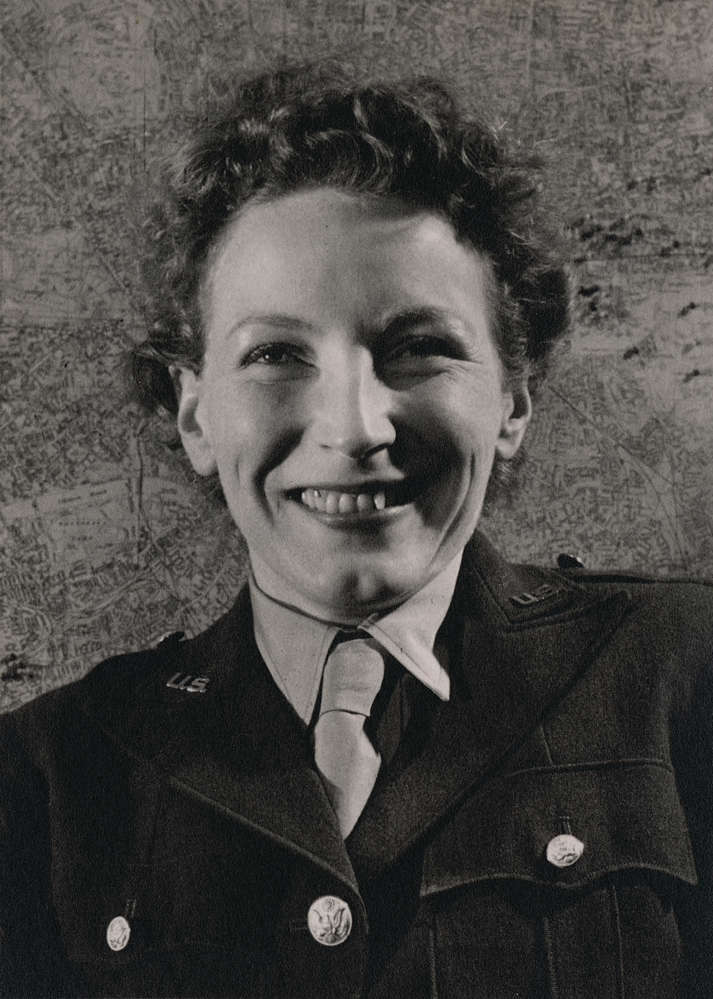

Mary Welsh was the first woman reporting on foreign affairs for Time magazine from wartime London. She narrowly escaped death from German bombs during the Blitz. One night, a piece of shrapnel exploded through the window and sliced through Mary’s ear lobe before blasting apart a sugar bowl. Mary saved the sugar before tending to her ear. She felt terrified as she realized how near death had come, yet she remained optimistic about the war’s outcome.

Mary’s editor, Walter Graebner, claimed, “Without doubt, she is the ablest female journalist in London.” And her fellow journalist, Michael Foot, later to become the leader of the British Labour Party, said: “Welsh is without question the best female journalist on either side of the Atlantic, apart altogether from being the most agreeable and amusing.”

As the Allies prepared to invade Normandy, hundreds of American officers and journalists passed through London. Mary described the city as: “a Garden of Eden” for single women. “There was a serpent dangling from every tree and streetlamp, offering tempting gifts and companionship, which could push away loneliness.”

These dalliances distracted women, and men, from “the hovering, shadowy sense of mortality.” Mary found comfort in the arms of several men, including the young American writer Irwin Shaw. Mary told her friend, Bill Walton, that: Irwin is “the best lay in Europe.” Shaw was handsome, with powerful shoulders, a muscular chest, strong arms, and the close-cropped head of a boxer.

Friday, May 26, 1944, was a bright, warm day in London. Mary strolled with Irwin Shaw up Rathbone Place to the lunch club at the restaurant. Mary wore a tailored jacket and skirt. Her seamstress had cut it down from one of her husband’s civilian suits. When Mary put on her sunglasses, Shaw said she looked fresh from Hollywood. And, since Shaw knew how women dressed in Hollywood, Mary appreciated the compliment. They neared the bistro on Percy Street (now a Vietnamese Restaurant called the House of Ho). Several men cast admiring glances, and one romantic soul swept off his hat and bowed. Mary felt good about herself.

The bistro owner, John Stais, tended tables in front of the White Tower. He greeted “Miss Mary” with a wave, and she blew him a kiss. The beautiful weather was drawing people outside, and Mary expected a full house at the lunch club. Inside the restaurant, they climbed the stairway to the first floor. “Coming up!” Shaw shouted. A large, bearded man turned to watch. He stared at Mary as if trying to fix her features in his memory, and the intensity of his gaze made her turn away.

Shaw followed Mary across the room to the reserved table, and she took a seat against the wall. When she looked up, she saw the imposing stranger continuing to stare at her. His temples showed gray, and he had oiled his longish hair. A gigantic beard formed a dark brown hedge with white sideburns extending under his jaw. Mary thought his brown eyes were beautiful, “lively and perceiving and friendly.” Shaw saw her looking at the big fellow and casually mentioned, “That’s Ernest Hemingway.”

Mary Welsh in her war correspondents’ uniform. Photo courtesy of Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

The room was so hot that Mary removed her jacket. She had refused her mother’s advice to wear bras since the age of twelve because she found them uncomfortable. As Mary slipped off the tight garment, a passing airman commented, “the warmth does bring things out, doesn’t it?” Mary took a long drag on her Camel cigarette. As she exhaled, she noticed Hemingway’s eyes trained on her, and he smiled, stood up, and came over to her table. Hemingway was a big man, as tall as her father. He had broad shoulders, a barrel chest, and slim hips; he looked fit and moved on the balls of his feet with the rhythm of a big cat.

Shaw introduced Ernest, who spoke softly and directly to Mary. Ernest told her he was a stranger in London and asked if she could brief him on the state of hostilities. Ernest had a mid-western accent, and his voice was younger sounding than Mary had expected. He shyly asked if she would have lunch with him the next day.

Mary was busy that weekend but agreed to meet him on Monday. Ernest beamed with the happiest face she had seen in a long time, and he turned sideways to negotiate the narrow staircase. Mary’s friends gossiped the second he disappeared, and Shaw feigned jealousy, saying it had been nice knowing her.

Mary regarded Ernest as another lonely man in a city full of lonely men, and it was not unusual for visiting journalists to ask her for a briefing. Still, celebrity is an aphrodisiac. Mary had felt his commanding presence, and she was pleased he had asked her out. Ernest became infatuated with Mary. She exuded self-confidence and sex appeal. He could not wait to see her again, and Ernest’s mood improved dramatically. His brother, Leicester, noted, “in a couple of days, Ernest was feeling personally admired again, and life was very pleasant around him.”

Mary spent the weekend at Time’s country retreat. In good weather, Mary and her friends sprawled on blankets on the lawn and read, rode bicycles, or hiked through the countryside. She rambled through the woods with her fellow journalist, Bill Walton, and mentioned her upcoming lunch with the famous novelist. Walton revealed that Leicester had earlier asked about Mary’s whereabouts to arrange a meeting with Ernest. Slowly, Mary realized the encounter with Hemingway was far more intriguing than she had first imagined. She wondered what Ernest had in mind. The thought of Ernest scheming amused her as she walked into the sunlight and saw the Chiltern Hills standing against a perfect blue sky.

Over the next year, Ernest pursued Mary enthusiastically. She was not immediately impressed, but Ernest was persistent, and eventually, Mary succumbed, agreed to take a one-year sabbatical from Time and moved to Ernest’s estate in Cuba. After a difficult adjustment period, including divorcing their spouses, Mary and Ernest married in Havana on March 14, 1946.

Excerpt from Hemingway’s Widow by Timothy Christian, published by Dundurn Press. Copyright 2022, Timothy Christian. Reprinted with permission.

Read more book excerpts, reviews and essays.